Goodbye, Darkness (42 page)

Just direct your feet

To the sunny side of the street

On the landward side of our little villa, a rock shaped like a griffin loomed over us like a misshapen monster, grimacing down. Little patches of fog, like gray suede, flecked the view of Yagachi; a mackerel sky foretold rain. But we were too grateful for the present to brood over the future. And in fact the sky cleared briefly for a splendid moment, revealing a carpet of damascened crimson mist suspended among the stars and the moon sailing serenely through a long white corridor of cloud, setting off the villa's flowering quince against a background of mango, jacaranda, and flamboyant trees.

In the absence of the enemy we freely lit up our Fleetwoods, talking among ourselves, the talk growing louder as the various conversations merged into a full-blown bull session, our first and last of the war. There was a little talk about combat, quickly exhausted when Swifty Crabbe said that true steel had to be tempered in fire. (Hoots silenced him.) Inevitably we also expatiated on quail, though not as coarsely as you might think. My generation of college men, I've been told over and over, enjoyed clinical discussions of coitus — “locker-room talk” — in which specific girls were identified. I never heard any of it, with one exception: a wheel in my fraternity who described foreplay with his fiancée and was therefore and thenceforth ostracized. He married the girl, stayed married to her, and is a major general today, but he is still remembered for that unforgivable lapse. I wouldn't have dreamed of mentioning Taffy to the section. I might have told them about Mae, had not the denouement been so humiliating, but that would have been different, partly because she advertised her horizontal profile but also because no one there knew her. Descriptions of vague, even imaginary, sexual exploits were OK; the important thing was never to damage the reputation of a girl who would be vulnerable to gossip.

We kept beating our gums by candlelight hour after hour, looking, I think now, for some evidence that one day the human race was going to make it. Somebody, Blinker, I think, said that war was a game of inches, like baseball; the width of your thumb could determine whether you were killed, wounded, or completely spared. I remember sprawling on my left hip, looking almost affectionately at my gunsels, one by one. There was Barney, of course, closer to me than my brother, and whippy Rip, who had almost broken my record on the Parris Island rifle range. Either of them, I believed, would have made a better sergeant than I was; I think they both knew it, but they rarely argued with me unless a life was at stake. Others in the section approached mutiny from time to time but were absolutely dependable in a crisis: Knocko, Horse, Mickey, Mo Crocker, who was always “Crock,” Swifty Crabbe, Pip, Izzy, Blinker, Hunky, Pisser McAdam, Killer Kane, and Dusty, a dark, animated youth whose quick eyes were useful on patrol. I could always count on lard-faced Bubba, despite my dislike of his racism and despite his bulbous head, which was shaped exactly like an onion. I felt protective toward Beau Tatum, Pip, Chet Przyastawaki, and Shiloh. Pip was just a kid, Beau was married, and the other two were engaged. Emotional attachments complicate a man's reactions in combat. Only two men really troubled me: Pisser and Killer Kane. Pisser was a biologist who resembled a shoat; he covered his lack of moxie, or tried to, with an aggressive use of slang which was already passing from the language: “snazzy,” “jeepers,” “nobby,” “you can say that again,” and “check and double-check.” Kane was fearsome only by name. He was a thin, balding radish of a youth with watery eyes; loose-jointed, like a marionette; who shuddered at the very sight of blood. Neither Pisser nor Kane had developed that ruthless suppression of compassion which fighting men need to endure battle. Neither, for that matter, had Wally Moon, but with Wally you couldn't be sure; none of us understood him; he played the absentminded scientist with brio. Wally was always wise about mechanics — cams, cogs, flanges, gaskets, bushings — but I knew he had been taught more than that at MIT. To me his outer man was rather like an unoccupied stage, with the essence of his character invisible in the wings. I had long ago forsaken hope of seeing him perform. But that night in Nakasoni the curtain parted a little.

He said crisply: “War has nothing to do with inches, or millimeters, or anything linear. It exists in another dimension. It is time. Heraclitus saw it five hundred years before Christ, and he wasn't the only one.” Wally talked about the Chinese yin and yang, Empedocles' Love and Strife, and, shifting back, Heraclitus's belief that strife — war — was men's “dominant and creative force, ‘father and king of us all.’” Hegel, he continued, picked this up and held that time was an eternal struggle between thesis and antithesis; then Marx, in the next generation, interpreted it as an inevitable conflict between the bourgeoisie and the proletariat. Jews, Christians, and Moslems all agreed that time would reach its consummation in a frightening climax. Before you could understand war and peace, Wally said, you had to come to grips with the nature of time, with awareness of it as the essence of consciousness. He said that the passage of time was probably the first phenomenon observed by prehistoric man, thus creating the concept of events succeeding one another in man's primitive experience.

Then the mechanic in Wally reemerged in what at first seemed an irrelevant tangent. Once men had perceived time as a stream of experience, he said, they began trying to measure it, beginning with the sun, the stars, the moon, the two equinoxes, and the wobbly spinning of the earth. In 1583 Galileo discovered the pendulum; seventy-three years later a Dutchman built the first pendulum clock. Splitting the day into 24 hours, or 86,400 seconds, followed. A.M. (ante meridiem, “before noon”) and P.M. (post meridiem, “after noon”) became accepted concepts on all levels of society — the week, having no scientific validity, varied by as much as three days from one culture to another — and in 1884 the world was divided into twenty-four time zones. The International Date Line, electromagnetic time, confirmation of Newton's laws of motion and gravitation, and the transmission of time signals to ships at sea, beginning in 1904 as navigational aids, united the civilized world in an ordered, if binding, time structure.

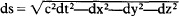

Thus far Wally had held us rapt. There were four Phi Beta Kappas in the section; he was talking the language we knew and loved. He hadn't come full circle yet — the pendulum clock's relationship to the battlefield was unclear — but that was the way of college bull sessions in my day, leading the others through a long loop before homing in on the objective. Unfortunately the loop sometimes went too far into uncharted territory and the speaker lost his audience. For a while there Wally was losing his. Chronometers and the value of rational time for navigation and geodetic surveys were understandable; so was Parmenides' argument that time is an illusion; so were the conclusions of Alfred North Whitehead and Henri Bergson that passing time could be comprehended only by intuition. But when Wally tried to take us into the fourth and fifth dimensions, citing Einstein's theory of special relativity and William James's hypothesis of the specious present, we began to stir and yawn. Like the old vaudeville act of Desiretta, the Man Who Wrestles with Himself, Wally was pinning himself to the mat. In my war diary I retained, but still do not understand, his equation for Minkowski's clock paradox:

It meant nothing then; it means nothing now. But bull sessions rarely ended on boring notes. Either someone changed the subject or the man with the floor, sensing the lethargy of the others, took a new tack. Wally quickly tacked back to his original objective. I had read Heraclitus and remember best one fragment of his work: “No man crosses the same river twice, because the river has changed, and so has the man.” Now Wally was reminding us that Heraclitus believed that the procession of time is the essence of reality, that there is only one earthly life. The riddle of time, Wally said, was baffling because no one knew whether it flowed past men or men passed through it — “If I fire my M1, does that mean that firing it is what the future was?” The point was not picayune; it was infinite. Either life was a one-way trip or it was cyclical, with the dead reborn. The life you lived, and the death you died, were determined by which view you held. Despite all evidence to the contrary, most thinkers, with the exception of the Egyptian era and the twentieth century, had come down hard on the side of rebirth. Plato, Aristotle, the fourteenth-century Moslem Ibn Khaldun, and Oswald Spengler believed men and civilizations were destined for rehabilitation. So did the biblical prophets: Abraham, Moses, Isaiah, and Jesus. All used the same evidence: the generational cycle and the cycle of the seasons.

It was at this point that Bubba astounded everyone by speaking up. He recited: “Unless a grain of wheat falls to the earth and dies, it remains alone; but, if it dies, it bears much fruit.” He trumpeted: “John 12:24.” There was a hush. Into it he tried to introduce certain observations of Robert Ingersoll, Dale Carnegie, and Emanuel Haldeman-Julius. Then Knocko — to my regret — turned him to dusky vermilion by saying gently, “Bubba, this is too deep for Dixie. The day they introduce the entrenching tool in Alabama, it'll spark an industrial revolution.” I should have said something, because Bubba was a fighter and therefore valuable to me, but I was eager to hear Wally's windup. And here it came. He said: “Like it or not, time really is a matter of relevance. We all have rhythms built into us. It wouldn't much matter if all the timepieces in the world were destroyed. Even animals have a kind of internal clock. Sea anemones expand and contract with the tides even when they are put in tanks. Men are a little different. John Locke wrote that we only experience time as a relationship between a succession of sensations. No two moments are alike. Often time drags. It dragged for most of us toward the end on the Canal. I think it won't drag much here. I have a feeling we are going to be living very fast very soon.”

Events confirmed him, though he didn't live to know it. He was right about the unevenness of the time flow, too. Time really is relative. Einstein wasn't the first to discover it — the ancients knew it, too, and so did some of the modern mystics. In our memories, as in our dreams, there are set pieces which live on and on, overriding what happened afterward. For some of my generation it was that last long weekend in Florida before Kennedy went to Dallas; Torbert MacDonald, his college roommate, was there, and afterward he said of that Palm Beach weekend that it reminded him of “way back in 1939, where there was nothing of any moment on anybody's mind.” History has other bittersweet dates: 1913, 1859, 1788 — all evoking the last flickering of splendor before everything loved and cherished was forever lost. That lazy evening in Nakasoni will always be poignant for me. I think of those doomed men, tough, idealistic, possessed of inexhaustible reservoirs of energy, and very vulnerable. So was I; so was I. But unlike them I didn't expect to make it through to the end. Thomas Wolfe, my college idol, had written: “You hang time up in great bells in a tower, you keep time ticking in a delicate pulse upon your wrist, you imprison time within the small, coiled wafer of a watch, and each man has his own, a separate time.” Out here in the Pacific, I thought, my time was coming; coming, as Wally said, very fast.

On Guam my dreams of the Sergeant begin to change. Color is returning; the sky is cerulean, the blood crimson; various shades of green merge in his camouflaged helmet cover. He himself, viewed now as through a prism, is subtly altered. His self-assurance has begun to ebb. And now, for the first time, there are intruders in the nightmares, shadowy figures flitting back and forth behind him. They seem sexless. I'm not even sure they are human. But on Guam, and in the nights to come elsewhere, they are always in the background — a chorus of Furies, avengers, whatever — and they have begun to distract the young NCO. He is becoming confused. He hesitates; his attention is divided; every third or fourth night I sleep through without any sign of him.

On the eighth day of the battle for Guam, Takeshi Takeshina, the Japanese commander, was killed in action. His army was finished, but those people never gave up. Organized resistance continued for two weeks; then the surviving Nips slipped into the hills to wage guerrilla warfare. Skirmishes continued until the end of the following year — seventeen weeks after Hirohito had surrendered to MacArthur — and even then diehards remained in the bush. Nine of them emerged from the jungle in the mid-1960s, and on February 9, 1972, a Nipponese soldier named Shoichi Yokoi ended his twenty-eight-year green exile and surrendered to amazed Guamanians, some of whom hadn't even been born when he disappeared from civilization. One by one the comrades who had shared his hideout had died. For the last nine years he had been alone, living on breadfruit, fish, coconut milk, and coconut meat. He had woven clothes from coir, and rope matting from shrubs, and he had fashioned implements from shell cases, coconut husks, and his mess gear. In Tokyo he was greeted as a national hero. It is sad to learn that he was deeply disappointed in what postwar Japan had become. I wonder if he had nightmares like mine.