Grumbles from the Grave (10 page)

Read Grumbles from the Grave Online

Authors: Robert A. Heinlein,Virginia Heinlein

Tags: #Authors; American - 20th century - Correspondence, #Correspondence, #Literary Collections, #Letters, #Heinlein; Robert A - Correspondence, #Science Fiction & Fantasy, #20th century, #Authors; American, #General, #Language Arts & Disciplines, #Science Fiction, #American, #Literary Criticism, #Science fiction - Authorship, #Biography & Autobiography, #Authorship

(46)

Red Planet,

Heinlein's 1949 juvenile for Scribner's, began the conflict between Heinlein and his editor Alice Dalgliesh.

Jim Marlowe, a teenaged Martian colonist, takes his pet Willis, a Martian bouncer, away to school with him. The headmaster impounds Willis, since pets are not allowed at school. Jim rescues the bouncer, and he and his friend Frank run away from school,taking Willis with them.

After a wild cross-country trek which includes a visit to a Martian building, the three are able to thwart a plot to prevent the colonists from making their annual migration. Thanks to Willis's ability to record exactly voices and words that he has heard, the colonists revolt against the plan, not wishing to live through an extremely cold Martian winter in high latitudes.

November 18, 1948: Robert A. Heinlein to Lurton Blassingame

Enclosed is a copy of notes for a new novel [

Red Planet

] for Miss Dalgliesh, plus a copy of the letter to her . . . Read the letters, read the notes as well, if you have time. Advice is welcomed.

The decision to postpone the ocean-rancher yarn [

Ocean Rancher

was supposed to be the third book in the Scribner's series, but it was never written.] called for a revision of my writing schedule. These are my present intentions: while Miss Dalgliesh is making up her mind, I intend to do one short story, 4,000 words, intended for adult, slick, general market, with

Post, Colliers, Town and Country, This Week,

and

Argosy

in mind. I should be able to show this to you by the middle of December.

If Miss Dalgliesh says yes, I will write the boys' novel next, planning to complete it before January 31. While she is looking it over, I expect to do another 4,000-word slick, following which I will revise the novel for Miss Dalgliesh. That should take me up to the end of February.

March 4, 1949: Robert A. Heinlein to Lurton Blassingame

There is actually no need for you to read this letter at all. It will not inform you on any important point, it will contain nothing calling for action on your part, and it probably will not even entertain you. I may not send it. I have a number of points to beef about, particularly Miss Dalgliesh; if Bill Corson [a friend who lived in Los Angeles] were here, I'd beef to him. He not being here, I take advantage of your good nature. I have come to think of you as a friend whom I know well enough to ask to listen to my gripes.

If Miss D. had said

Red Planet

was dull, I would have had no comeback. We clowns either make the audience laugh or we don't; if we entertain, we are successes; if we don't, we are failures. If she had said, "The book is entertaining but I want certain changes. Cut out the egg-laying and the disappearances. Change the explanation for the Old Martians," I would have kept my griping to myself and worked on the basis that the Customer Is Always Right.

She did neither. In effect she said, "The book is gripping, but for reasons I cannot or will not define I don't want to publish it."

I consider this situation very different from that with the publisher in Philadelphia who first instigated the writing of

Rocket Ship Galileo.

He and I parted amicably; he wanted a book of a clearly defined sort which I did not want to write. But, from my point of view, Miss Dalgliesh ordered this particular book; to wit, she had a standing arrangement for one book a year from me; she received a

very

detailed outline which she approved. She got a book to that outline, in my usual style. To my mind that constitutes an order and I know that other writers have been paid their advance under similar circumstances. I think Scribner's owes us, in equity, $500 even if they return the manuscript. A client can't take up the time of a doctor, a lawyer, or an architect, under similar circumstances without paying for it. If you call in an architect, discuss with him a proposed house, he works up a floor plan and a treatment; then you decide not to go further with him, he goes straight back to his office and bills you for professional services, whether you have signed a contract or not.

My case is parallel, save that Miss Dalgliesh let me go ahead and "build the house," so to speak.

I think I know why she bounced the book—I use "bounced" intentionally; I hope that you do not work out some sort of a revision scheme with her because I do not think she will take this book, no matter what is done to it.

I think she bounced the book from some ill-defined standards of

literary snobbishness—it's not "Scribner's-type" material!! I think that point sticks out all through her letter to me. I know that such an attitude has been shown by her all through my relationship with her. She has spoken frequently of "cheap" books, "cheap" magazines. "Cheap," used in reference to a story, is not a defined evaluation; it is merely a sneer—usually a sneer at the format from a snob.

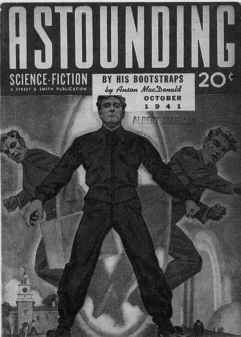

She asked me to suggest an artist for

Rocket Ship Galileo

; I suggested Hubert Rogers. She looked into the matter, then wrote me that Mr. Rogers' name "was too closely associated with a rather cheap magazine"—meaning John Campbell's

Astounding S-F.

To prove her point, she sent me tear sheets from the magazine. It so happened that the story she picked to send was one of my "Anson MacDonald" stories, "By His Bootstraps"—which at that time was again in print in Crown's

Best in Science Fiction

!

(48)

Dalgliesh's infamous example of Hubert Rogers' cover for the "cheap" magazine, John W. Campbell's

Astounding,

featuring "By His Bootstraps" by Heinlein's own alias, Anson MacDonald.

I chuckled and said nothing. If she could not spot my style and was impressed only by the fact that the stuff was printed on pulpwood paper, it was not my place to educate her. I wondered if she knew that my reputation had been gained in that same "cheap" magazine and concluded that she probably did not know and might not have been willing to publish my stuff had she known.

Rogers is a very fine artist. As an illustrator he did the trade editions of John Buchan's books. I am happy to have one of his paintings hanging in my home. In place of him she obtained someone else. Take a look at the copy of

Galileo

in your office—and don't confuse it in your mind with the fine work done by [Clifford N.] Geary for

Space Cadet.

The man she picked is a fairly adequate draftsman, but with no ability to turn an illustration into an artistically satisfying composition. However, he had worked for Scribner's before; he was "respectable."

I think I know what is eating her about

Red Planet.

It is not any objection on her part to fantasy or fairy tales as such; she is very proud of having published

The Wind in the Willows.

Nor does she object to my pulp-trained style; she accepted it in two other books. No, it is this: She has fixed firmly in her mind a conception of what a "science fiction" book should be, though she can't define it and the notion is nebulous—she has neither the technical training nor the acquaintance with the body of literature in the field to have a clearly defined criterion. But it's there, just the same, and it reads something like this: "Science has to do with machines and machinery and laboratories. Science fiction consists of stories about the wonderful machines of the future which will go striding around the universe, as in Jules Verne."

Her definition is all right as far as it goes, but it fails to include most of the field and includes only that portion of the field which has been heavily overworked and now contains only low-grade ore. Speculative fiction (I prefer that term to science fiction) is also concerned with sociology, psychology, esoteric aspects of biology, impact of terrestrial culture on the other cultures we may encounter when we conquer space, etc., without end. However, speculative fiction is

not

fantasy fiction, as it rules out the use of anything as material which violates established scientific fact, laws of nature, call it what you will, i.e., it must [be] possible to the universe as we know it. Thus,

Wind in the Willows

is fantasy, but the much more incredible extravaganzas of Dr. Olaf Stapledon are speculative fiction—

science fiction.

I gave Miss Dalgliesh a story which was strictly science fiction by all the accepted standards—but it did not fit into the narrow niche to which she has assigned the term, and it scared her—she was scared that some other person, critic, librarian, or whatever, a literary snob like herself—would think that she had published comic-book type of material. She is not sufficiently educated in science to distinguish between Mars as I portrayed it and the wonderful planet that Flash Gordon infests, nor would she be able to defend herself from the charge if brought.

As a piece of

science

fiction,

Red Planet

is a much more difficult and much more carefully handled job than either of the two books before it. Those books contained a little straightforward descriptive astronomy, junior high school level, and some faked-up mechanical engineering which I could make sound authoritative because I am a mechanical engineer and know the patter. This book, on the other hand, has a planetary matrix most carefully worked out from a dozen different sciences all more complicated and esoteric than descriptive astronomy and reaction engines. Take that one little point about how the desert cabbage stopped crowding in on the boys when Jim turned on the light. A heliotropic plant would do just that—but I'll bet she doesn't know heliotropism from second base. I did not attempt to rub the reader's nose in the mechanics of heliotropism or why it would develop on Mars because she had been so insistent on not being "too technical."

I worked out in figures the amount of chlorophyll surface necessary to permit those boys to live overnight in the heart of a plant and how much radiant energy would be required before I included the incident. But I'll bet she thought of that incident as being "fantasy."

I'll bet that, if she has ever heard of heliotropism at all, she thinks of it as a plant "reaching for the light." It's not; it's a plant spreading for light, a difference of ninety degrees in the mechanism and the point that makes the incident work.

Between ourselves there is one error deliberately introduced into the book, a too-low figure on the heat of crystallization of water. I needed it for dramatic reasons. I wrote around it, concealed it, I believe, from any but a trained physicist looking for discrepancies, and I'll bet ten bucks she never spotted it!—she hasn't the knowledge to spot it.

Enough of beating that dead horse! It's a better piece of

science

fiction than the other two, but she'll never know it and it's useless to try to tell her. Lurton, I'm fed up with trying to work for her. She keeps poking her nose into things she doesn't understand and which are my business, not hers. I'm tired of trying to spoon-feed her, I'm tired of trying to educate her diplomatically. From my point of view she should judge my work by these rules and these only: (a) will it amuse and hold the attention of

boys?

(b) is it grammatical and as literate as my earlier stuff? (c) are the moral attitudes shown by the author and his protagonists—not his villains—such as to make it suitable to place in the hands of minors?

Actually, the first criterion is the only one she need worry about; I won't offend on the other two points—and she knows it. She shouldn't attempt to judge science-versus-fantasy; she's not qualified. Even if she were and even if my stuff were fantasy, why such a criterion anyhow? Has she withdrawn

Wind in the

Willows from the market? If she thinks

Red Planet

is a fairy tale, or a fantasy, but gripping (as she says) to read, let her label it as such and peddle it as such. I don't give a damn. She should concern herself with whether or not boys will like it. As a matter of fact, I don't consider her any fit person to select books to suit the tastes of boys. I've had to fight like hell to keep her from gutting my first two books; the fact that boys

did

like them is a tribute to my taste, not to hers. I've read a couple of the books she wrote for girls—have you tried them? They're dull as ditch water. Maybe girls will hold still for that sort of things; boys

won't.

I hope this works out so that we are through with her. I prefer pocketing the loss, at least for now, to coping with her further.

And I don't like her dirty-minded attitude over the Willis business. Willis is one of the closest of my imaginary friends; I loved that little tyke, and her raised eyebrows infuriate me. [Willis is the young Martian adopted as a pet by the hero; it's Willis who often gets him out of trouble.]

March 15, 1949: Robert A. Heinlein to Lurton Blassingame

First, your letter: the only part that needs comment is Miss D's remark about getting a good Freudian to interpret the Willis business. There is no point in answering her, but let me sputter a little. A "good Freudian" will find sexual connotations in

anything

—that's the basis of the theory. In answer I insist that without the aid of a "good Freudian"

boys

will see nothing in the scene but considerable humor. In

Space Cadet

a "good Freudian" would find the rockets "thrusting up against the sky" definite phallic symbols. Perhaps he would be right; the ways of the subconscious are obscure and not easily read. But I still make the point that

boys are not psychoanalysts

—nor will anyone with a normal healthy sex orientation make anything out of that scene. I think my wife, Ginny, summed it up when she said, "She's got a dirty mind!"