Hacking Happiness (31 page)

Authors: John Havens

•

We may soon get to the point where information from outside sources regarding a survey could come into play regarding data collection. In the same way three reporters can cover a story three different ways, other people’s responses to your actions may begin to factor into surveys you take. For instance, say you self-reported that a previous day had been fairly calm. If two other people using Google Glass devices recorded you at a Starbucks where you raised your voice at a barista, their impressions of your behavior might register differently than your own memory. Sensors measuring your behavior outside of the ones you’re wearing will likely come into play very soon for large-scale measurement of happiness and well-being.

Why Happiness?

Our politicians, media, and economic commentators dutifully continue to trumpet the GDP figures as information of great portent . . . There has been barely a stirring of curiosity regarding the premise that underlies its gross statistical summation. Whether from sincere conviction or from entrenched professional and financial interests, politicians, economists, and the rest have not been eager to see it changed. There is an urgent need for new indicators of progress, geared to the economy that actually exists.

8

—CLIFFORD COBB, TED HALSTEAD,

and

JONATHAN ROWE

Jon Hall is the head of the National Human Development Reports Unit (HDRO), part of the United Nations Development Programme. Before joining the HDRO, Hall spent seven years working for the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), where he led the Global Project on Measuring the Progress of Societies. He recently was lead author of Issues for a Global Human Development Agenda for HDRO and has been actively involved in research around human development and well-being since 2000. He is also advising the H(app)athon Project and provided me with

a history of the Beyond GDP movement in an interview for

Hacking H(app)iness

. “Happiness is a single number that goes up and down and can easily be interpreted,” Hall noted in our interview, pointing out the power of a single and simple unifying metric to measure well-being. “That’s how I became converted about happiness as a single overarching metric of progress.”

9

As a statistician, Hall became aware early in his work around well-being how important it was to create metrics that the average citizen could understand. As he noted in his interview for this book, after developing a groundbreaking report for the Australian Bureau of Statistics called

Measuring Australia’s Progress

, Hall showed the report to his mother for her thoughts. “She said, ‘I love the picture of my grandson on the cover, but it has too many numbers, so I gave it to your father.’”

It’s a fun story, but points out the disconnect Jon has been trying to eradicate for years: How can we make what we measure matter to the average citizen? One way is to keep things simple, which is why Jon favors the use of happiness metrics to measure life satisfaction.

Happiness provides a broad summary of how people feel about their lives. It doesn’t require statisticians or economists to add things up and take an average. Adding metrics together like health or education often gets people upset because the formulas complicate things: How does an extra year of life compare to an extra year of education, for example? There is no “right” answer. Happiness relies on people answering a simple question about how they feel.

10

One of the more popular ways to measure life satisfaction or happiness is called the Cantril Ladder Scale (or self-anchoring striving scale), developed by Hadley Cantril in 1965 at Princeton University. People rate their lives based on an imaginary ladder

where the steps are numbered zero to ten. Zero represents the worst possible life, and ten represents the best.

While people’s responses to these questions are inherently subjective, they do provide a way for people to simply express how they feel on a certain issue. As Hall points out, the more you collect these kinds of assessments, the more insights you also gain about a community, and the more the results can inspire conversations about things that matter.

One aggregate number changing around happiness is easy to collect and it can fluctuate for a multitude of reasons based on people’s concerns. The difference between socioeconomic groups can also be telling: If the measure goes up or down for a certain group, then that can trigger a conversation. Imagine if the government regularly reported measures of happiness, and imagine if happiness for white young women in Florida dropped last week, then that might trigger a broader debate in the media. Is it because of recent reports of rape? Is it because of reports that women in the state earn less than men? . . . And so on, and so on. The statistics can provide a window into a broader set of conversations that go beyond GDP: They can be very powerful ways to inspire much broader and informed debates around issues that are relevant to citizens.

11

Social media is providing another platform for studying happiness and well-being that can help to soften our single-minded focus toward the GDP. The World Well-Being Project (WWBP), part of the Positive Psychology Center at the University of Pennsylvania, is leveraging the massive availability of citizen commentary available through social media platforms to analyze psychosocial and physical well-being. By measuring language through sentiment analysis and other similar methodologies, the WWBP also gets to leverage

the scale of social media to analyze large data sets for mining insights around happiness and well-being. The group’s vision is that their “insights and analyses can help policy makers to determine those policies that are not just in the best economic interest of the people, but those which indeed further people’s well-being.”

12

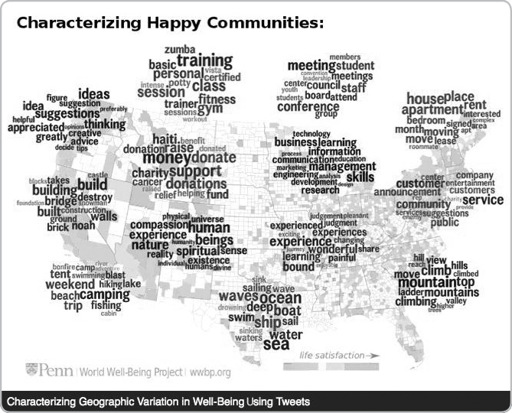

One of WWBP’s studies, “Characterizing Geographic Variation in Well-Being Using Tweets,” showed that “language used in tweets from 1,300 different U.S. counties was found to be predictive of the subjective well-being of people living in those counties as measured by representative surveys.”

13

A word cloud visualization of the report can be seen below. This practice of utilizing social media to study well-being sets a fascinating precedent, especially if results mirror surveys focused on the same issues. Citizens get to utilize transparent tools to broadcast their emotions, while organizations like the WWBP help analyze sentiment that could lead to policy change.

Evolution

From 2000 to the present, a number of initiatives and organizations have helped push the envelope to move Beyond GDP. One big push came from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). In the early 2000s, the organization created a focus on measuring well-being for its thirty or so member states focused on global development. As Jon Hall noted in our interview, “The OECD getting involved in this work was a big stamp of approval; it gave the study of happiness and well-being a whole new level of seriousness.”

14

The organization created an interactive Better Life Index, which lets users rate eleven topics in real time to see how OECD member countries compare based on each issue. The topics reflect what the OECD feels are essential to both material living conditions (housing, income, jobs) and quality of life (community, education, environment, governance, health, life satisfaction, safety, and work-life balance).

In 2007, the OECD held a world forum on Measuring and Fostering the Progress of Societies in Istanbul, and the EU organized a Beyond GDP conference, hosted by the European Commission, the European Parliament, the Club of Rome, the OECD, and the World Wildlife Fund, which met to discuss which indicators would be most appropriate to measure progress in the world. In 2008, President Nicolas Sarkozy of France created the Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress focused on evolving the GDP. The commission was chaired by renowned economist Joseph Stiglitz.

After a number of other initiatives took place over the following years, in 2012 the United Nations implemented Resolution 65/309, a provision that permitted the Kingdom of Bhutan to convene a high-level meeting as part of the sixty-sixth session of the UN General Assembly in New York City. The Resolution recognized

“that the gross domestic product . . . does not adequately reflect the happiness and well-being of people,” and “that the pursuit of happiness is a fundamental human goal.”

15

On April 2, 2012, the prime minister of Bhutan convened the summit titled, “Wellbeing and Happiness: Defining a New Economic Paradigm.” The report from the meeting outlines a series of next steps attending organizations are taking to implement measures of well-being and happiness to move Beyond GDP. The prime minister of Bhutan, H.E. Mr. Jigmi Y. Thinley, opened the meeting with the following remarks:

We desperately need an economy that serves and nurtures the well-being of all sentient beings on earth and the human happiness that comes from living life in harmony with the natural world, with our communities, and with our inner selves. We need an economy that will serve humanity, not enslave it. It must prevent the imminent reversal of civilization and flourish within the natural bounds of our planet while ensuring the sustainable, equitable, and meaningful use of precious resources.

16

The meeting was a watershed event in terms of the world formally looking to dismantle or at least complement the GDP with factors directly related to increasing measures of well-being, happiness, and flourishing that cannot be created or sustained by money alone.

Building Genuine Wealth

Mark Anielski is president and CEO of Anielski Management in Edmonton, Alberta, and author of the best-selling book

The Economics of Happiness: Building Genuine Wealth

. I interviewed Anielski about his ideas based on his experience in Canada with natural

capital accounting and work developing alternative measures of economic progress beyond the GDP. One of the initial aspects of his book I found so compelling was in the introduction where he states, “Economics is more like a religion than either art or science.”

17

I asked him to elaborate on this idea.

Economics is like a religion because it demands that society accept certain axioms, theories, principles, and suppositions about how human beings behave. Economics would have us believe that all people are consumers measured in terms of GDP, where everything is valued in terms of a money “price” that mediates all transactions and human relations. However, the idea that all people behave in a similar fashion in some hypothesized maximization of utility is a convenient simplification of how people actually behave. The trouble is, if you don’t believe in these theories, then you find yourself outside of the “religion” of neoclassical economics. But the truth is, people are not rational and do not behave the same. There is no such thing as a perfect market.

18

It’s helpful to redefine economics as a study of people’s behavior versus simply the output of their labor. Well-being is multifaceted and relies on numerous cultural biases and predispositions that can’t be unilaterally measured by algorithms or indexes that don’t truly represent how people or communities work.

According to Anielski, Genuine Wealth must inherently factor in the human and environmental capital of a country or it won’t accurately measure what truly brings well-being to its citizens. And one of the reasons we’ve stayed with the GDP as a measure of value for so long is simply how hard it is to calculate these attributes as compared to utilizing fiscal metrics. But with Gross National Happiness and the Beyond GDP movement gaining trac

tion, governments around the world are being pressured to use more transparent and accountable methods to measure what truly brings contentment in modern society. I asked Anielski about these ideas in relation to my thoughts on accountability-based influence and how our actions on individual and collective levels would begin to alter how the world views wealth moving forward:

I believe that genuine accountability will result when businesses and governments operate from the basis of a true balance sheet that keeps an account of the physical and qualitative conditions of its human (people), social (relationships), and natural capital assets. In the Genuine Wealth model I’ve developed, the measures of progress and proxies for the resilience or flourishing of assets will be tied to virtues, values, and principles for what people intuitively feel contributes most to their well-being. We will then be able to confidently say we are measuring what matters.

19