Hanns Heinz Ewers Alraune (39 page)

Read Hanns Heinz Ewers Alraune Online

Authors: Joe Bandel

Tags: #alraune, #decadence, #german, #gothic, #hanns heinz ewers, #horror, #literature, #translations

“Speak,” she urged. “Do you believe that I am

your insolent joke–that took form? Your idea, which the old Privy

Councilor threw into his crucible, which he cooked and distilled,

until something came out that now sits before you?”

This time he didn’t hesitate, “If you put it

that way, yes, that’s what I believe.”

She laughed softly, “I thought so–and that’s

why I waited up for you tonight. To cure you of this vanity as soon

as possible. No, cousin. You didn’t throw this idea into the world,

not you–not any more than the old Privy Councilor did.”

He didn’t understand her.

“Then who did?” he asked.

She reached under the pillow with her

hand.

“This did!” she cried.

She lightly tossed the little alraune into

the air and caught it again, caressed it lovingly with nervous

fingers.

“That there? Why that?” he asked.

She gave back, “Did you think about it

earlier–before the day the Legal Councilor celebrated the communion

of the two children?”

“No,” he replied. “Certainly not.”

But then this thing fell down from the wall,

that was when the idea came to you! Isn’t that true?”

“Yes,” he confessed. “That is how it

was.”

“Now then,” she continued, “so the idea came

from outside somewhere and entered into you. It was when Attorney

Manasse gave his lecture, when he recited like a school book and

explained to all of you what this little alraune was and what it

meant–That’s when the idea grew in your brain. It became so large

and so strong that you found the strength to suggest it to your

uncle, to persuade him to carry it out, to create me.

Then, if I am only an idea that came into the

world and took on human form, it is also true that you, Frank

Braun, were only an agent, an instrument–no more than the Privy

Councilor or his assistant doctor. No different than–”

She hesitated, fell silent, but only for a

moment. Then she continued–

“than the prostitute, Alma and the

rapist-murderer whom you all coupled–you and Death!”

She laid the little alraune on the silk

cushions, looked at it with an almost loving glance and said,” You

are my father: You are my mother. You are what created me.”

He looked at her.

“Perhaps it was so,” he thought.

Ideas whirl through the air, like the pollen

from flowers and play around before finally sinking into someone’s

brain. Often they waste away there, spoil and die–Only a few find

good rich soil–

“Perhaps she was right,” he thought.

His brain had always been a fertile planting

place for all kinds of foolishness and abstruse fantasies. It

seemed the same to him, whether he was the one that once threw the

seed of this idea into the world–or whether he was the fertile

earth that had received it.

But he remained silent, left her with her

thought. He glanced over at her, a child, playing with her doll.

She slowly stood up, not letting the little manikin out of her

hands.

“There is something else I want to tell you,”

she spoke softly. “But first I want to thank you for it, for giving

me the leather bound volume and not burning it.

“What is it?” he asked.

She interrupted herself.

“Should I kiss you?” she asked. “I could

kiss–”

“Was that all you wanted to say, Alraune?” he

said.

She replied, “No, not that!–I only thought I

would like to kiss you once. Just in case–But first I want to tell

you this, why I waited. Go away!”

He bit his lips, “Why?”

“Because–because it would be better,” she

answered, “for you–perhaps for me as well. But it doesn’t depend on

that–I now know how things are–am now enlightened, and I think that

things will continue to go as they have–only, I will not be running

around blindly anymore–Now I see everything. Soon–soon it will be

your turn, and that’s why it would be better if you left.”

“Are you so certain of this?” he asked.

“Don’t I need to be?”

He shrugged his shoulders, “Perhaps, I don’t

know. But tell me, why do you want to do this for me?”

“I like you,” she said quietly. “You have

been good to me.”

He laughed, “Weren’t the others as well?”

“Yes,” she answered. “They all were. But I

didn’t see it. And they–all of them–they loved me–you don’t–not

yet.”

She went to the writing desk, took a postcard

and gave it to him.

“Here is a postcard from your mother. It came

earlier this evening; the servant brought it up with my mail by

mistake. I read it. Your mother is ill–She very much begs you to

come back to her.”

He took the postcard, stared in front of him

undecided. He knew that they were right, both of them, could feel

it, that it was foolishness to remain here. Then a boyish defiance

seized him that screamed out, “No! No!”

“Will you go?” she asked.

He forced himself, spoke with a determined

voice, “Yes, cousin!”

He looked at her sharply, watched every line

of her face searching for some movement, a little tug at the

corners of her mouth, a little sigh would have been enough, some

something that showed him her regret. But she remained quiet and

serious. No breath moved on her inflexible mask.

That vexed him, wounded him, seemed like an

affront and an insult to him. He pressed his lips solidly

together.

“Not like this,” he thought. “I won’t go like

this.”

She came up to him, reached out her hand to

him.

“Good,” she said. “Good–Now I will go. I can

give you a goodbye kiss if you want.”

A sudden fire flickered in his eyes at

that.

Without even wanting to, he said, “Don’t do

it Alraune. Don’t do it!”

And his voice took on her own tone.

She raised her head and quickly asked, “Why

not?”

Again he used her words, but she sensed that

it was on purpose.

“I like you, Alraune,” he said. “You have

been good to me today–many red lips have kissed my mouth–and they

became very pale. Now–now, it would be your turn. That is why it

would be better if you didn’t kiss me!”

They stood facing each other; their eyes

glowed hard as steel. Unnoticed, a smile played on his lips. His

weapon was bright and sharp. Now she could choose. Her “No” would

be his victory and her defeat–then he could go with a light heart.

But her “Yes” would mean war and she felt it–the same way he did.

It was like that very first evening, exactly the same, only that

time was the beginning and opening round. There had still been hope

for several other rounds in the duel. But now–it was the end. He

was the one that had thrown the glove–

She took him up on it.

“I am not afraid,” she spoke.

He fell silent and the smile died on his

lips–Now it was serious.

“I want to kiss you,” she repeated.

He said, “Be careful! I will kiss you

back.”

She held his gaze–“Yes,” she said–Then she

smiled.

“Sit down, you are a little too tall for

me!”

“No,” he cried out loudly. “Not like

that.”

He went to the wide divan, laid down on it,

buried his head in the cushions, stretched his arms out wide on

both sides, closed his eyes.

“Now, come Alraune!” he cried.

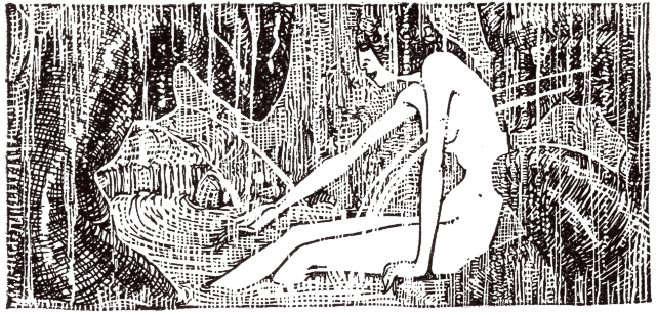

She stepped closer, kneeled by his hips,

hesitated, looked at him, then suddenly threw herself down onto

him, seized his head, pressed her lips on his. He didn’t embrace

her, didn’t move his arms. But his fingers tightened into fists. He

felt her tongue, the light bite of her teeth.

Kiss harder,” he whispered. “Kiss

harder.”

Red fog lay before his eyes. He heard the

Privy Councilor’s repulsive laugh, saw the large piercing eyes of

Frau Gontram, how she begged little Manasse to explain the little

alraune to her. He heard the giggling of the two celebrants, Olga

and Frieda, and the broken, yet still beautiful voice of Madame de

Vére singing “Les Papillons”, saw the small Hussar Lieutenant

listening eagerly to the attorney, saw Karl Mohnen, as he wiped the

little alraune with the large napkin–

“Kiss harder!” he murmured.

And Alma–her mother, red like a burning

torch, snow-white breasts with tiny blue veins, and the execution

of her father–as Uncle Jakob had described it in his leather bound

volume–Out of the mouth of the princess–And the hour, in which the

old man created her–and the other, in which his doctor brought her

into this world–

“Kiss me,” he moaned, “Kiss me.”

He drank her kisses, sucked the hot blood

from his lips, which her teeth had torn, and he became intoxicated,

knowingly and intentionally, as if from champagne or his oriental

narcotics–

“Enough,” he said suddenly, “enough, you

don’t know what you are doing.”

At that she pressed her curls more tightly

against his forehead, her kisses became hotter and more wild. Now

the clear thoughts of day lay shattered, now came the dreams,

swelling on a blood red ocean, now the Maenad swung her thyrsos and

he frothed in the holy frenzy of Dionysus.

“Kiss me,” he screamed.

But she released him, let her arms sink. He

opened his eyes, looked at her.

“Kiss me!” he repeated softly.

Her eyes glazed over, her breath came in

short pants. Slowly she shook her head. At that he sprang up.

“Then I will kiss you,” he cried.

He lifted her up in his arms, threw her down

struggling onto the divan, knelt down–there, right where she had

knelt.

“Close your eyes,” he whispered and he bent

down–

Good, his kisses were good–caressing and

soft, like a harp played on a summer night, wild too, yes, and raw,

like a storm wind blowing over the North sea. They burned red-hot

like the fiery breath out of mount Aetna, ravishing and consuming

like the vortex of a maelstrom–

“It’s pulling me under,” she felt, “pulling

me into it.”

But then the spark struck and burning flames

shot high into the heavens, the burning torch flew, ignited the

altar, and with bloody jowls the wolf sprang into the

sanctuary.

She embraced him, pressed herself tightly to

his breast–I’m burning–she exalted–I’m burning–at that, he tore the

clothes from her body.

The sun that woke her was high in the sky.

She saw that she was lying there completely naked, but didn’t cover

herself. She turned her head, saw him sitting up right next to

her–naked like she was.

She asked, “Will you be leaving today?”

“Is that what you want, that I should leave?”

he gave back.

“Stay,” she whispered. “Stay!”

Tells how Alraune lived in the park.

H

E

didn’t write his mother on that day, or the

next, pushed it off for another week and further–for months. He

lived in the large garden of the Brinkens, like he had done when he

was a boy, when he had spent his school vacations there.

They sat in the warm green houses or under

the mighty cedars, whose young sprouts had been brought from

Lebanon by some pious ancestor, or strolled under the Mulberry

trees, past a small pool that was deeply overshadowed by hanging

willows.

The garden belonged to them that summer, to

them alone, Alraune and him. The Fräulein had given strict orders

that none of the servants were permitted to enter, not by day or by

night. Not once were the gardeners called for. They were sent away

into the city, charged with the maintenance of her gardens at her

villas in Coblenz. The renters were very happy and amazed at the

Fräulein’s attentiveness.

Only Frieda Gontram used the path. She never

spoke a word about what she suspected but didn’t know. But her

pinched lips and her evasive glance spoke loudly enough. She

avoided meeting him on the path and yet was always there as soon as

he was together with Alraune.

“What the blazes,” he grumbled. “I wish she

was on top of mount Blocksberg!”

“Is she bothering you?” asked Alraune.

“Doesn’t she bother you?” he retorted.

She replied, “I haven’t noticed. I scarcely

pay any attention to her.”

That evening he encountered Frieda Gontram by

the blossoming blackthorns. She stood up from her bench and turned

to go. Her gaze held a hot hatred.

He went up to her, “What is it Frieda?”

She said, “Nothing!–You can be satisfied now.

You will soon be free of me.”

“Why is that?” he asked.

Her voice trembled, “I must go–tomorrow!

Alraune told me that you didn’t want me here.”

An infinite misery spoke out of her

glance.

“You wait here, Frieda. I will speak with

her.”

He hurried into the house and came back after

a short time.

“We have thought it over,” he began, “Alraune

and I. It is not necessary that you go away–forever. Frieda, it’s

only that I make you nervous with my presence–and you do the same

for me, excuse me for saying it. That’s why it would be better if

you go on a journey–only for awhile. Travel to Davos to visit your

brother. Come back in two months.”