Hanns Heinz Ewers Alraune (40 page)

Read Hanns Heinz Ewers Alraune Online

Authors: Joe Bandel

Tags: #alraune, #decadence, #german, #gothic, #hanns heinz ewers, #horror, #literature, #translations

She stood up, looked at him with questioning

eyes that were still full of fear.

“Is that the truth?” she whispered. “Only for

two months?”

He answered, “Certainly it’s true. Why should

I lie Frieda?”

She gripped his hand; a great joy made her

face glow.

“I am very grateful to you!” she said.

“Everything is alright then–as long as I am permitted to come

back!”

She said, “Goodbye,” and headed for the

house, stopped suddenly and came back to him.

“There is something else, Herr Doctor,” she

said. “Alraune gave me a check this morning but I tore it up,

because–because–in short, I tore it up. Now I will need some money.

I don’t want to go to her–she would ask–and I don’t want her to

ask. For that reason–will you give me the money?”

He nodded, “Naturally I will–Am I permitted

to ask why you tore the check up?”

She looked at him, shrugged her

shoulders.

“I wouldn’t have needed the money any more if

I had to leave her forever–”

“Frieda,” he pressed, “where would you have

gone?”

“Where?” A bitter laugh rang out from her

thin lips. “Where? The same place Olga went! Only, believe me,

doctor. I would have achieved my goal!”

She nodded lightly to him, walked away and

disappeared between the birch trees.

Early, when the young sun woke him, he came

out of his room in his kimono, went into the garden along the path

that led past the trellis and into the rose bed. He cut white Boule

de Neige roses, Queen Catharine roses, Victoria roses, Snow Queen

roses and Merveille de Lyon roses. Then he turned left where the

larches and the silver fir trees stood.

Alraune sat on the edge of the pool in a

black silk robe, breaking breadcrumbs, throwing them to the

goldfish. When he came she twined a wreath out of the pale roses,

quickly and skillfully making a crown for her hair.

She threw off her robe, sat in her lace

negligee and splashed in the cool water with her naked feet–She

scarcely spoke, but she trembled as his fingers lightly caressed

her neck, when his soft breath caressed her cheek. Slowly she took

off the negligee and laid it on the bronze mermaid beside her.

Six water nymphs sat around the marble edge

of the pool pouring water out of jugs and urns, spraying thin

streams out of their breasts. Various animals crept around them,

giant lobsters, spiny lobsters, turtles, fish, eels and other

reptiles. In the middle of the pool Triton blew his horn as chubby

faced merfolk blew mighty streams of water high into the air around

him.

“Come, my friend,” she said.

Then they both climbed into the water. It was

very cold and he shivered, his lips became blue and goose bumps

quickly appeared on his arms. He had to swim vigorously, beat his

arms and tread water to warm his blood and get accustomed to the

unusual temperature.

But she didn’t even notice, was in her

element in an instant and laughing at him. She swam around like a

little frog.

“Turn the faucet on!” she cried.

He did it. There, near the pool’s edge, by

the statue of Galatea, light waves came from the water as well as

three other places in the pool. They boiled up a little, growing

stronger and higher, climbing higher and higher, until they became

enormous sparkling cascades of silvery rain, higher than the

spouting streams of the mermen.

There she stood between all four, in the

middle of a shimmering rain, like a sweet boy, slender and

delicate. His long glance kissed her. There was no blemish in the

symmetry of her limbs, not the slightest defect in this sweet work

of art. Her color was in proportion as well, like white marble with

a light breath of yellow. Only the insides of her thighs showed two

curious rose colored lines.

“That’s where Dr. Petersen perished,” he

thought.

He bent down, kneeled and kissed the rosy

places.

“What are you thinking about?” she asked.

He said, “ I’m thinking that you are the

fairy Melusine!–See the little mermaids around us–they have no

legs, only long, scaly fish tails. They have no souls, these

nymphs, but it is said that sometimes they love a human, some

fisherman or wandering knight.

They love him so much that they come out of

the water at high tide, out onto the land. Then they go to an old

witch or shaman–that brews some nasty potion they have to drink.

Then the shaman takes a sharp knife and begins to cut into the fish

tail. It is very painful–very painful, but Melusine suppresses her

pain. Her love is so great that she doesn’t complain, doesn’t cry

out, until the pain becomes so great she looses consciousness. But

when she awakes–her little tail is gone and she goes about on two

beautiful legs–like a human–only the scars where the shaman cut are

still visible.”

“But wasn’t she always still a nymph?” she

asked. “Even with human legs?–And the sorcerer could never create a

soul for her.”

“No,” he said. “He couldn’t do that, but

there is something else they say of nymphs.”

“What do they say?” she asked.

He explained, “She only has her strange power

as long as she is untouched. When she drowns in the kisses of her

lover, when she looses her maidenhood in her knight’s embrace–then

she looses her magic as well. She can no longer bring river gold

and treasures but the black sorrow that followed her can no longer

cross her threshold either. From then on she is like any other

child of man–”

“If it only was!” she whispered.

She tore the white crown from her head, swam

over to the mermen and Triton, to the water nymphs and threw the

rose blossoms into their laps–

“Take them, sisters–take them!” she laughed.

“I am a child of man–”

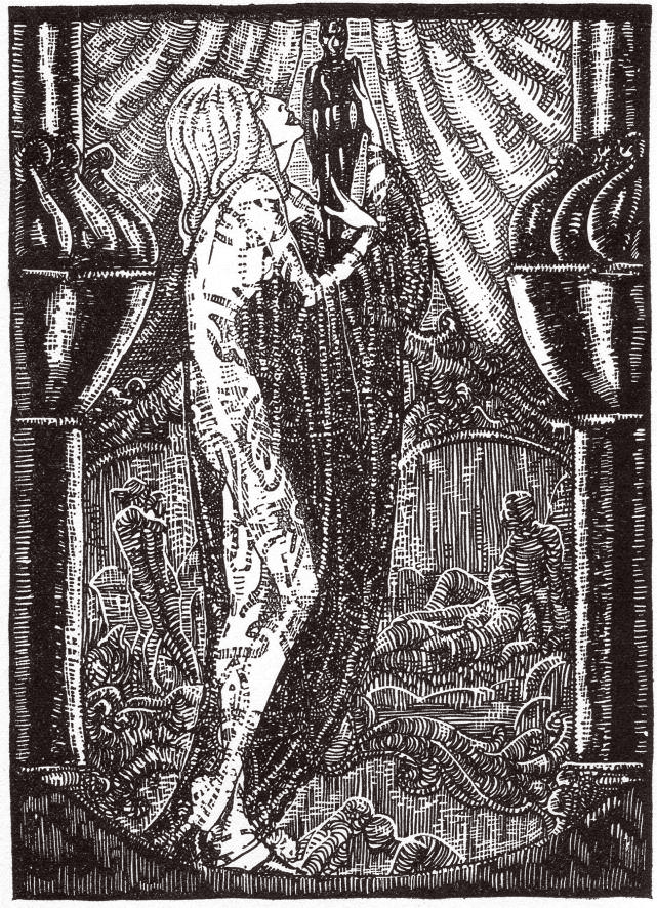

An enormous canopy bed stood in Alraune’s

bedroom on low, baroque columns. Two pillars grew out of the foot

and bore shelves that shown with golden flames. The engraved sides

showed Omphale with Hercules in a woman’s dress as he waited on

her, Perseus kissing Andromeda, Hephaestus catching Ares and

Aphrodite in his net–Many tendrils of vines wove themselves in

between and doves played in them–along with winged cherubs. The

magnificent ancient bed, heavily gilt with gold, had been brought

out of Lyons by Fräulein Hortense de Monthy when she became his

great-grandfather’s wife.

He saw Alraune standing on a chair at the

head of the bed, a heavy pliers in her hand.

“What are you doing with that?” he asked.

She laughed, “Just wait. I will soon be

finished.”

She pounded and tore, carefully enough, at

the golden figurine of Amor that hovered at the head of the bed

with his bow and arrow. She pulled one nail out, then another,

seized the little god, twisted him this way and that–until he came

loose. She grabbed him, jumped down, laid him on top of the

wardrobe, took out the Alraune manikin, clambered back up onto the

chair again with it and fastened it to the head of the bed with

wire and twine. Then she came back down and looked critically at

her work.

“How do you like it?” she asked him.

“Why should the little man be there?” he

retorted.

She said, “He belongs there!–I didn’t like

the golden Cupid–That is for all the other people–I want to have

Galeotto, my root manikin.”

“Why do you call it that?” he asked.

“Galeotto!” she replied. “Wasn’t it him that

brought us together?–Now I want him to hang there, to watch over us

through the night.”

Sometimes they went out riding in the

evenings or also during the night if the moon was shining. They

rode through the Sieben Gerberge mountain range or to Rolandseck

and into the wilderness beyond.

I want him to hang there, to watch over us

through the night

Once they found a she-donkey at the foot of

Dragon’s Rock in the Sieben Geberge mountain range. People there

used the animal for riding up to the castle at the top. He bought

her. She was a young animal, well cared for and glistened like

fresh snow. Her name was Bianca. They took her with them, behind

the horses on a long rope, but the animal just stood there,

planting her forelegs like a stubborn mule, allowing herself to be

choked and dragged along.

Finally they found a way to persuade her. In

Kőnigswinter he bought a large bag full of sugar, took the rope off

Bianca and let her run free. He threw her one piece of sugar after

the other from out of the saddle. Soon the she-donkey ran after

them, keeping itself tight to his stirrup, snuffling at his

boots.

Old Froitsheim took the pipe out of his mouth

as they came up, spit thoughtfully and grinned agreeably.

“An ass,” he chewed. “A young ass! It’s been

almost thirty years since we’ve had one here in the stable. You

know, young Master, how I used to let you ride old gray

Jonathan?”

He got a bunch of carrots and gave them to

the animal, stroking her shaggy fur.

“What’s her name, young Master?” he

asked.

Frank Braun told him her name.

“Come Bianca,” spoke the old man. “You will

have it good here with me. We will be friends.”

Then he turned again to Frank Braun.

“Young Master,” he continued. “I have three

great-grandchildren in the village, two little girls and a boy.

They are the cobbler’s children, on the road to Godesberg. They

often come to visit me on Sunday afternoons. May I let them ride

the ass?–Just here in the yard?”

He nodded, but before he could answer the

Fräulein cried out:

“Why don’t you ask me, old man? It is my

animal. He gave it to me!–Now I want to tell you–you are permitted

to ride her–even in the gardens, when we are not home.

Frank Braun’s glance thanked her–but not the

old coachman. He looked at her, half mistrusting and half

surprised, grumbled something incomprehensible and enticed the

donkey into the stable with the juicy carrots.

He called the stable boy, presented him to

Bianca, then the horses, one after the other–led her around behind

the farmyard, showed her the cow barn with the heavy Hollander cows

and the young calf of black and white Liese. He showed her the

hounds, both sharp pointers, the old guard dog and the cheeky fox

terrier that was sleeping in the stable. Brought her to the pigs,

where the enormous Yorkshire sow suckled her piglets, to the goats

and the chicken coop. Bianca ate carrots and followed him. It

appeared that she liked it at the Brinken’s.

Often in the afternoons the Fräulein’s clear

voice rang out from the garden.

“Bianca!” she cried. “Bianca!”

Then the old coachman opened her stall; swung

the door open wide and the little donkey came into the garden at an

easy trot. She would stop a few times, eat the green juicy leaves,

indulge in the high clover or wander around some more until the

enticing call rang out again, “Bianca!” Then she would search for

her mistress.

They lay on the lawn under the ash trees. No

table–only a large platter lay on the grass covered with a white

Damascus cloth. There were many fruits, assorted tid-bits, dainties

and sweets among the roses. The wine stood to the side.

Bianca snuffled, scorned the caviar and no

less the oysters, turned away from the pies. But she took some cake

and a piece of ice out of the cooler, ate a couple of roses in

between–

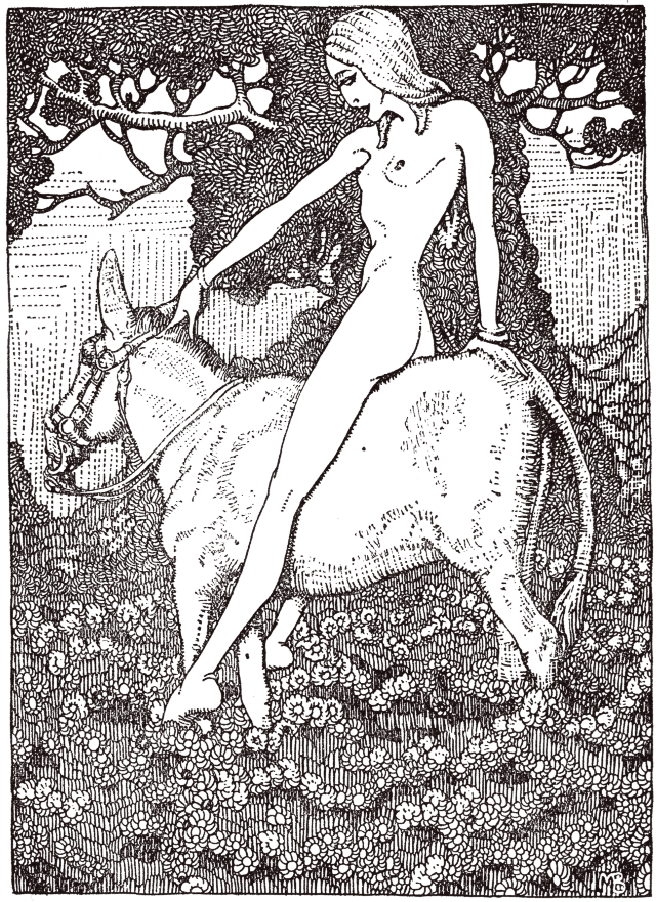

“Undress me!” said Alraune.

Then he loosened the eyes and hooks and

opened the snaps. When she was naked he lifted her onto the donkey.

She sat astride on the white animal’s back and held on lightly to

the shaggy mane. Slowly, step by step, she strode over the meadow.

He walked by her side, lying his right hand on the animal’s head.

Bianca was clever, proud of the slender boy whom she carried,

didn’t stop once, but went lightly with velvet hoofs.

There, where the dahlia bed ended, a narrow

path led past the little brook that fed the marble pool. She didn’t

go over the wooden bridge. Carefully, one foot after the other,

Bianca waded through the clear water. She looked curiously to the

side when a green frog jumped from the bank into the stream. He led

the animal over to a raspberry patch, picked the red berries and

divided them with Alraune, continued through the thick laurel

bushes.

There, surrounded by thick elms, lie a large

field of carnations. His grandfather had laid it out for his good

friend, Gottfried Kinkel, who loved these flowers. Every week he

had sent the poet a large bouquet for as long as he lived. There

were little feathery carnations, tens of thousands of them, as far

as the eye could see. All the flowers glowed silver-white and their

leaves glowed silvery green. They gleamed far, far into the evening

sun, a silver ground.