Hatchepsut: The Female Pharaoh (7 page)

Read Hatchepsut: The Female Pharaoh Online

Authors: Joyce Tyldesley

Tags: #History, #Africa, #General, #World, #Ancient

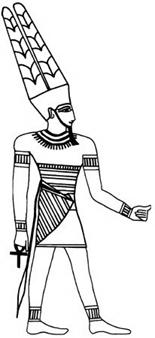

Fig. 1.5 The god Amen

Amen had started life as an insignificant and rather colourless local deity worshipped in the immediate area around Thebes. However, he was quickly to become the most powerful god in the Egyptian Empire, associated with the most important Old Kingdom deity in the compound god Amen-Re, linked with the fertility god Min of Coptos in his ithyphallic form and accorded the magnificent title ‘King of the Gods and Lord of the Thrones of the Two Lands’. Iconographically, Amen most commonly appears as a man dressed in a short kilt and sporting a distinctive feathered headdress of two tall plumes. His sacred animals are the goose and, far more importantly, the ram, and his main cult centre is the Karnak temple at Thebes. Egyptian

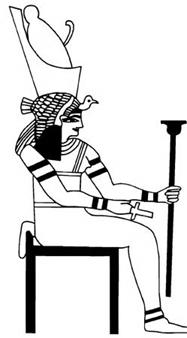

gods do not usually come singly but as members of divine families of three; Amen's consort is the anthropoid goddess Mut (‘Mother’), a lady who has links with both the mother-goddesses Hathor and Bast and with the fierce lion-headed goddess of war and sickness, Sekhmet, and their son is the local moon-god, Khonsu. Mut's cult centre is an impressive temple enclosure directly to the south of Amen's at Karnak, while Khonsu was worshipped in a temple im-mediately to the north.

Fig. 1.6 The goddess Mut

Egypt's new prosperity allowed the 18th Dynasty pharaohs to endow shrines and temples to various gods throughout the land. These new buildings were now built of stone rather than mud-brick and were literally designed to last for all eternity. Major cities such as Thebes and Memphis, previously home to relatively modest mud-brick chapels, now found themselves dominated by massive, painted stone temples. These were typically surrounded by clusters of relatively unimpressive mud-brick buildings housing lesser shrines and administrative offices, the whole temple complex being enclosed by a high, thick mud-brick wall of military appearance, designed to keep the common people out. The Egyptian temple was not the equivalent of a medieval cathedral; it was the private home of the god who, in the form of a statue, dwelt within. The temple gates were rarely thrown open to the general public and, while many townsmen must have worked on the temple buildings, few would have been aware of the mysteries surrounding the daily practice of their state religion. Indeed, although the ordinary people owed an official allegiance to the state gods, they were far more likely to worship their less exalted and more familiar local gods, while folk-religion, including magic,

superstition and witchcraft, played an important role in the life of the peasant communities.

By the middle of the 18th Dynasty, Thebes had become a major religious centre with a full range of temples and shrines dedicated not only to Amen and his family but to a whole host of lesser deities. On the western bank of the Nile, opposite Thebes, were the mortuary temples of the kings, the tombs of the élite citizens and, hidden away in the Valley of the Kings, the tombs of the pharaohs themselves. All New Kingdom monarchs showed their extreme devotion to Amen by trying to outdo their predecessors in embellishing the Karnak complex itself, and a considerable amount of Egypt's new-found foreign wealth was diverted towards the Great Temple of Amen so that it grew physically, becoming an economic force in its own right and employing an increasingly large staff to carry out the cult ceremonies and administer the god's extensive portfolio. Theban state religion was now organized on a far more professional basis and the hitherto private deity started to make a series of well-organized public parades through the streets, a tradition which allowed the people to enjoy a day's holiday while subtly underlining the magnificence and omnipresence of the god and his priesthood.

By the middle of the New Kingdom, the religious foundations controlled an estimated one-third of the cultivated land and employed approximately twenty per cent of the population. Amen himself owned not only temples but major secular investments such as fields, ships, mines, quarries, villages and even prisoners of war who had been donated by the grateful monarchy. The income from these assets, together with the routine daily offerings of thousands of loaves of bread and hundreds of jugs of beer plus costlier foodstuffs including wine and meat, was collected by Amen's earthly representatives and was used to pay the temple employees. Surpluses were stored in vast mud-brick warehouses kept safe within the temple walls. Within a very short time the Amen temple at Karnak was second only to the throne itself as a centre of economic and political influence in Egypt.

Perhaps it is modern cynicism which prompts present-day historians to question why the 18th Dynasty monarchs should have deliberately chosen to raise the cult of Amen to state god status, thereby creating an

immensely wealthy and semi-independent priesthood capable of posing a threat to the throne. The simple answer, that the kings felt a strong devotion to their patron deity, may well be the true one. However, it is tempting to see the rise of Amen as a more calculated gesture, perhaps aimed at reducing the influence of the northern-based cult of Re. Promoting a new Egyptian state god, one who had demonstrated his powers by granting victory in battle, may have been a shrewd move aimed at unifying a demoralized country recovering from the ignominy of foreign rule. It would certainly have helped the position of the new pharaoh who, as chief priest of all the gods, and indeed as the very son of Amen, had the power to interpret the god's wishes as he saw fit. Hatchepsut herself was to make great use of her filial relationship with Amen, continually stressing the doctrine of the divine birth of kings to support her claim to the throne. However, this mutual dependency could prove to be a two-edged sword. Any public failure by the new god, such as a refusal to grant further victories to the Egyptian army, could be taken as a direct sign that the king himself was failing to perform his duties correctly, and a powerful and wealthy priesthood could ultimately bring about the fall of a weak or inefficient king.

By the late 18th Dynasty, the monarchy was starting to feel itself challenged by the power and ever-increasing wealth of the cult of Amen. Amenhotep II, Tuthmosis IV and Amenhotep III all appointed their own loyal followers to the position of High Priest in an attempt to maintain a degree of royal control over the priesthood, while Amenhotep III also started to pay more attention to the other gods of the Egyptian pantheon, partially reverting back to Old Kingdom theology by re-allying the monarchy with the sun god, Re of Heliopolis. His son, Amenhotep IV (now known as the heretic King Akhenaten, ‘Serviceable to the Aten’), took this policy to extremes by completely rejecting the traditional polytheistic religion and imposing a new monotheistic cult based on the worship of the sun disc, or Aten, on his people. This radical change, which included the establishment of a new capital in the desert of Middle Egypt, was too extreme for the conservative Egyptians, and far too much of a threat to the power of Amen. It was doomed to failure. By Year 3 of his successor's reign, the old gods, including Amen, had been reinstated and the new king had changed his name from Tutankhaten, ‘Living Image of the Aten’, to Tutankhamen, ‘Living Image of Amen’.

... all the wealth that goes into Thebes of Egypt, where treasures in greatest store are laid up in men's houses. Thebes, which is the city of an hundred gates and from each issue forth to do battle two hundred doughty warriors with horses and chariots.

17

The early 18th Dynasty rulers broke with tradition when they established their capital at their home-city of Thebes. Thebes, or Thebai, is the Greek name for the southern city which the Egyptians officially knew as Waset but which they referred to simply as ‘The City’ (literally

Niwt

), and which modern Egyptians now call Luxor. The new capital lay on the east bank of the Nile in the 4th Upper Egyptian province, close enough to both Nubia and the Eastern Desert to be able to benefit from the lucrative trade routes, and far enough away from the northern capital Memphis to have always maintained semi-independent status. Thebes had been an unimportant provincial town throughout the Old Kingdom, and it was not until the civil unrest of the First Intermediate Period that the local Theban rulers started to gain in power and influence. By the time of Ahmose, Thebes had expanded to become an extensive city, and the Theban necropolis on the west bank of the Nile had become the main burial ground for the pharaohs, their families and the higher-ranking court officials. During the 18th Dynasty, however, the old city mound was completely flattened to allow the redevelopment of the Karnak temple, and the residential area was rebuilt on relatively low-lying ground which now lies below the water-table and which is consequently lost from the archaeological record.

Living conditions within Thebes must have been, for all but the most wealthy, somewhat unpleasant during the hot summer months. There was a permanent shortage of building land, made much worse by the extension of the Karnak and Luxor temples, and there was no formal planning policy so that, as the city expanded, the houses were packed more and more closely together, blocking the light from the crowded and twisting streets. The lack of any form of official sanitation combined with the habit of keeping animals within the home to create an undesirable, vermin-ridden environment that must have been highly unhealthy for the unfortunate citizens. However, although many were forced by the nature of their employment to live in the overcrowded towns and cities, Egypt was still a predominantly rural country and the

majority of Egyptians lived relatively healthy lives working as peasant farmers in small and politically insignificant agricultural communities. Throughout the New Kingdom it was fashionable to despise city life as a necessary evil while rural life strongly – romanticized – was considered to be ideal. Just as modern city dwellers dream of owning a cottage in the country, so Egyptian officials yearned for a spacious single-storey villa set in its own grounds away from the bustle, noise and smells of the city. For the higher echelons of society, this dream could become a reality which would continue into the Afterlife; their heaven took the form of the ‘Field of Reeds’, an idyllic rural retreat where noblemen, their wives and daughters would spend eternity supervising the labours of others less fortunate than themselves.

Thebes did, however, boast one example of a well-planned community. The workmen's village of Deir el-Medina, simply ‘the Village’ to its inhabitants, was founded by Amenhotep I and largely built by Tuthmosis I in order to provide a convenient base for those employed in the cutting and decoration of the royal tombs in the nearby Valley of the Kings and Valley of the Queens. Situated on the West Bank, opposite Thebes and over a mile away from the River Nile, the Village was of necessity built of a combination of stone and mud-brick. For this reason the Village has survived where others, built entirely of mud-brick, have crumbled to dust, and is now able to provide us with a vivid insight into the daily lives of a specialized section of Egypt's middle and working classes. Deir el-Medina experienced over four hundred years of continuous occupation by not only the workmen and their supervisors but their families, dependants, pets and those providing ancillary services such as potters, priests and laundry workers. By the 19th Dynasty up to seventy families – about three hundred people – lived in the modest rectangular houses which had been laid out with all the precision of a modern American city, within a defining wall. Beyond the wall there was a cemetery, a collection of chapels for private worship, and possibly a subsidiary village intended to house the lowest-ranking servants and serfs. Every month a gang of male workers would leave the Village and head for the Valley of the Kings, where they lodged in temporary accommodation for up to twenty-seven working days. Back at the Village, daily life continued as in any normal Egyptian town or city for as long as the king was able to provide the rations which served as wages. During the 18th Dynasty,

a period of economic strength and efficient administration, the workmen's Village functioned well.

Although Thebes may be regarded as the new state capital, and certainly as the new religious capital, the idea of the single predominant city was now of far less importance than it had been during the Old Kingdom when Egypt had been ruled from the northern city of Memphis. Memphis was at that time not only the largest Egyptian city, it was the site of the main royal residence and the administrative centre, and nearby were both the royal burial grounds and the major cult centre of Re. In many ways her geographical position made Memphis a far more suitable capital city than Thebes. Situated at the crossroads between the two traditional regions of Upper (Southern) and Lower (Northern, or Delta) Egypt, Memphis enjoyed excellent communications with both north and south. Although an inland city, Memphis, on the River Nile, was the site of the royal dockyards, and the city flourished as a marine trading centre. Furthermore, Memphis made an ideal base for the army. Following the southern campaigns of Tuthmosis I, Nubia, although given to frequent rebellions, could offer no real threat to the might of Egypt. The real danger was perceived as coming from the Levant, where semi-independent city-states were starting to unite under the banners of the powerful rulers of Kadesh, Mitanni and the Hittites. We know that Tuthmosis I built a large palace/barrack at Memphis, and it seems likely that throughout the 18th Dynasty the state bureaucracy was still controlled to a large extent from that city. Unfortunately, little of ancient Memphis has survived to be excavated.