Hatchepsut: The Female Pharaoh (11 page)

Read Hatchepsut: The Female Pharaoh Online

Authors: Joyce Tyldesley

Tags: #History, #Africa, #General, #World, #Ancient

The plans of surviving New Kingdom harem-palaces show groups of independent mud-brick buildings including living quarters, storerooms and a chapel or shrine, all surrounded by a high mud-brick wall. The living quarters took the form of enclosed structures focused inwards towards a central open area or courtyard which sometimes contained pools of water. This may be compared with the traditional modern Islamic harem of the early twentieth century, a large house built around a courtyard which might include a pool or fountain, and surrounded by high walls.

17

The physical setting of the more modern harem was very firmly focused inwards towards the central open space which became the scene of the daily activities of the harem-women. Here food was prepared, cosmetics were applied, and the days and evenings were spent singing, dancing and telling stories.

The dynastic Egyptian harem-palace served both as a nursery for the royal infants and as the ‘Household of the Royal Children’, the most prestigious school in the land. Here the young male royals, under the supervision of the ‘Overseer of the Royal Harem’ and the ‘Teacher of the Royal Children’, received the instruction which would prepare them for their future lives as some of the highest-ranking nobles in the land. The title ‘Child of the Palace’ (that is, a royal child, or one important enough to be brought up as one) is one often used by high officials from the Middle Kingdom onwards, the full reading in the New

Kingdom being ‘Child of the Palace of the Royal Harem’. Important 18th Dynasty officials who chose to emphasize their childhood connection with the royal court include the Viziers Rekhmire, Ramose and Amenemope, the High Priest of Amen, Hapuseneb, and the Mayor of Thebes, Sennefer. Childhood networking in the royal harem must have been of crucial importance to those living in a state where everyone's career and status was dependent upon their relationship with the king.

At any time of civil unrest, given the high mortality rates amongst the male élite engaged in physical combat, we might expect to find the embattled monarchy placing a great reliance on the production of male children both to ensure the royal succession, be it father to son (for example, Sekenenre Tao to Kamose) or brother to brother (for example, Kamose to Ahmose) and to provide loyal subordinate military leaders. However, this does not appear to be the case at the start of the New Kingdom when the more minor male royal personages – the second sons and younger brothers of kings – take their turn at becoming invisible. With the younger males this is not so remarkable as both male and female royal children tended to be relatively obscure in infancy and childhood; their early invisibility did not necessarily prevent them from achieving fame later in their careers. However, the lack of adult princes is something of a puzzle, particularly at a time when the vast increase in numbers of royal wives might have led us to expect a dramatic increase in royal children.

In part, the invisibility of the royal sons must be a result of the selective preservation of the historical records, and in particular the royal monuments. The temples and funerary monuments of Thebes and the West Bank are covered with texts and scenes depicting various kings who are occasionally shown together with their queens and the royal princesses. However, the royal family only appear in these scenes as symbolic appendages of the king; they are not intended to be seen as independent individuals in their own right and indeed New Kingdom royal art is full of images of dependant royal woman who often appear as minuscule figures barely reaching to the knees of the colossal king who is their husband, father or both. The fact that sons are unlikely to appear as royal dependents in these scenes should therefore not be taken as an indication that they lacked importance, but rather as confirmation that they were expected to live a more independent existence. The princess was given respect as the daughter (or property?) of the king;

the prince had to earn his own respect. This in turn implies that while the position of King's Daughter was very much seen as a role in its own right, the role of King's Son was merely an accident of birth, not a fulltime career. The crown prince was obviously an exception to this rule; as heir to the throne he was born with a clearly defined role and was often given the post of Great Army General to reinforce his status, just as the British heir to the throne is traditionally created Prince of Wales.

If royal sons are less likely to appear on royal monuments than their sisters then where, apart from their tombs, are we likely to find them? Even the location of their tombs poses a problem, as princely burials dating to the early 18th Dynasty are virtually unknown, although recent discoveries in the Valley of the Kings suggest that groups of princes may have been buried in batches in mass burial chambers. We do have examples of 18th Dynasty individuals classifying themselves as ‘King's Son' but, for some reason, we have no one claiming to be a ‘King's Brother’. This had led to the intriguing suggestion that royal princes may have in some way lost their royalty once the crown prince had produced an heir, thereby casting them outside the direct line of succession. This would have the effect of restricting the royal family to the king, his unmarried sisters, his spinster aunts, his mother and grandmother and his children; his brothers and uncles would no longer be regarded as fully royal, although they would still be entitled to a respected place in the community.

18

This automatic pruning of the royal family would have the advantage of reducing the number of individuals with a potential claim to the throne and would presumably keep the royal family securely exclusive. Whatever their official status, we can see that those princes who grew to adulthood before the death of their father received high-ranking appointments in the priesthood, the army and the civil service. The fate of their younger, orphaned brothers is less certain.

The best place to look for the missing 18th Dynasty princes is the workmen's village of Deir el-Medina. Here, throughout the 19th Dynasty and particularly during the reign of Ramesses II, the early 18th Dynasty royal family was regarded with great reverence. On a general level they were honoured as both the (theoretical) ancestors of the current kings and as excellent role models for military kingship, while on a more personal level the inhabitants of Deir el-Medina worshipped the Theban royal family as both the founders of their village and the

initiators of the ultimate in job-creation schemes in the Valley of the Kings. The villagers had good reason to worship their partially deified patrons Amenhotep I and Ahmose Nefertari, and it is not surprising that these two demi-gods appear on many small monuments, sometimes standing alongside other Theban deities such as Hathor, Lady of the West. Occasionally, however, the inhabitants of Deir el-Medina chose to commemorate the lesser members of the Theban royal family, including some of the missing princes. The best-known example of this is found in the tomb of a man named Khabekhnet, where the northeastern wall shows two rows of seated, named individuals who are identified as ‘Lords of the West’. Included amongst these are some who are clearly the sons of kings who did not succeed their father to the throne. Unfortunately, beyond their names, we have little further information about these lost princes.

From the scanty records surviving from the beginning of the Eighteenth Dynasty, it emerges that a remarkable part was played in the history of the newly unified state by three ladies, Tetisheri and Ahhotpe… and Ahmose Nefertiry… There can be little doubt that their behaviour served as an inspiration to the leading women of the country (of whom Hatchepsut is the leading example) throughout the Eighteenth Dynasty.

19

King Ahmose was blessed with not only a strong grandmother but with a forceful and politically active mother. Ahhotep I (or Ahhotpe, as above), consort and possibly sister of Sekenenre Tao II, exerted a profound and long-lasting influence on her son; on a stela recovered from Karnak, Ahmose encourages his people to pay homage to his mother as the ‘one who has accomplished the rites and taken care of Egypt’:

She has looked after her [that is, Egypt's] soldiers, she has guarded her, she has brought back her fugitives and collected together her deserters, she has pacified Upper Egypt and expelled her rebels.

20

The precise meaning of this curious stela is now lost to us. However if, as it seems to maintain, Ahhotep herself had truly been able to thwart a rebellion by mustering the Egyptian troops, she must have been a woman capable of wielding real rather than ceremonial power. We may even deduce that Ahhotep had been called upon to act as regent

following the untimely death of Kamose because we know that when Ahmose died at the end of his 25-year reign he was relatively young, possibly only in his early thirties. We know of no formal declaration of a regency, but there was certainly a well-established precedent for the dowager queen to act as regent for her young son; the 2nd Dynasty Queen Nemaathep had acted as regent for King Djoser and the 6th Dynasty Queen Ankhes-Merire had ruled on behalf of her six-year-old son Pepi II. Why the queen should be chosen to act as regent in preference to a male relation (perhaps father's brother) is now unclear, although we can speculate that it would be the mother above all who would safeguard her son's inheritance. If the theory of the royal princes losing their royalness on the assumption of their brother holds true, there would in any case be no close male member of the royal family available to take on the role.

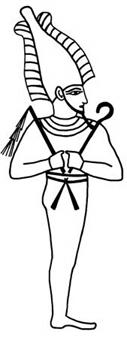

There was certainly a clear divine precedent for a mother taking care of her son's inheritance. The story of Isis and Osiris tells how Osiris, rightful king of Egypt in the time of the gods, was murdered by his jealous brother Seth. Seth cut Osiris' body into many pieces which he scattered all over Egypt. Isis, his devoted wife and sister, toiled to collect the bits together and, with her magic powers, granted Osiris temporary life. So successful was her magic that nine months later their son Horus was born. The dead Osiris then became king of the Afterlife. Meanwhile the resourceful Isis hid Horus from his uncle in the marshes until he became a man, able to avenge his father's death. The women of Egypt were not routinely expected to display such initiative; they generally took a more passive role in society. However, decisive behaviour was acceptable and even to be encouraged in a female if that behaviour was intended to safeguard the rights of either a husband or child.

After her death Ahhotep was accorded a splendid burial on the West Bank at Thebes. Her mummy in its elaborate coffin was recovered in the mid nineteenth century, and is now housed in the Cairo Museum.

Although both Tetisheri and Ahhotep had been honoured by Ahmose it was his wife, Ahmose Nefertari, who first received the formal accolades which were to become the right of future queens of Egypt. Ahmose Nefertari, ‘King's Daughter and King's Sister’, ‘Female Chieftain of Upper and Lower Egypt’, wife and probably sister of Ahmose, mother of Amenhotep I, granddaughter of Tetisheri and possibly

daughter of Kamose, was even more influential than her redoubtable mother-in-law. Unfortunately we have no text detailing her specific achievements, but we do know that Ahmose Nefertari was either given, or sold, the prestigious title of ‘Second Prophet of Amen’, a post which was intended to belong to the queen and her descendants for ever.

Fig. 2.2 The god Osiris

The queen later renounced this title for an even more prestigious position, the priestly office of ‘God's Wife of Amen’, an honour which came with its own endowment of goods and land plus a staff of male administrators and which, given the rising importance of the cult of Amen at this time, was a clear indication of the enhanced status of the queen. It is perhaps cynical to suggest that the position may have been deliberately contrived to allow the royal family some measure of control over the increasingly powerful and wealthy cult. Ahmose Nefertari obviously saw this as her most important role, and used the title of ‘God's Wife of Amen in preference to any other. Contemporary illustrations show the queen dressed in a distinctive short wig and strangely archaic-looking clothes as she performs the religious duties associated with her new office. Unfortunately, we have little understanding of the precise function of the God's Wife; the title suggests that it should have been borne either by those queens who had coupled with Amen to produce a king (that is, by queen mothers), or by unmarried women who had dedicated themselves to the service of Amen, but a quick

survey of the women who held the post shows that neither explanation can be correct. Hatchepsut, for example, was neither a virgin nor the mother of a king. It is possible, however, that the role related in some (theoretical) way to the sexual stimulation of the god which would ensure the renewal of the land: a second and less deli-cate title, ‘God's Hand’, which is occasionally used in conjunction with ‘God's Wife’, is an unmistakable reference to the masturbation which produced the first gods, Shu and Tefnut.