Hatchepsut: The Female Pharaoh (12 page)

Read Hatchepsut: The Female Pharaoh Online

Authors: Joyce Tyldesley

Tags: #History, #Africa, #General, #World, #Ancient

Fig. 2.3 The god Horus

The role of ‘God's Wife of Amen' was passed down from Ahmose Nefertari to her daughter Meritamen, and then to Hatchepsut who used it until she became king, when it was transferred to her daughter Neferure. The title fell into decline during the solo reign of Tuthmosis III – perhaps the new king had experienced enough powerful women – and died out completely after the reign of Tuthmosis IV, only to be revived during the Third Intermediate Period when, having merged with the position of ‘Divine Adoratrice’, it developed into a politically and economically highly significant post. The God's Wife of Amen now had theoretical control over the vast wealth of the estates of Amen.

Ahmose Nefertari fulfilled her wifely duties by presenting her husband-brother with at least four sons and five daughters, five of whom died in infancy or childhood. However, she was not content to restrict herself to breeding and abandoned the traditional shelter of the queen's palace:

To judge from the number of inscriptions, contemporary and later, in which that young queen's name appears, she obtained as celebrity almost without parallel in the history of Egypt.

21

Setting a precedent now followed by modern royal couples, the queen accompanied her husband as he performed his many civic duties; we know that when Ahmose opened a new gallery at the Tura limestone quarry in his regnal Year 22, he was accompanied by his queen who stood modestly behind her husband in a typical wifely pose. The queen also seems to have assisted her husband in developing his building projects and, as we have already noted, Ahmose consulted his wife over his plans to honour their dead grandmother, Tetisheri. She was certainly active in the religious sphere; her piety, or perhaps her independent wealth, led her to dedicate far more religious offerings than any previous queen and offerings presented by Ahmose Nefertari have been found in temples as far apart as Karnak in the south and Serabit el-Khadim in the Sinai Peninsula.

Following the death of Ahmose, Ahmose Nefertari took on the role of regent for her young son, Amenhotep I, handing over the reins of state when her son became old enough to rule. Throughout his 21-year reign, Amenhotep I consolidated the successful foreign policies started by his father, uncle and grandfather. There was no further military action in Palestine, but the army ex- further south into Nubia where a viceroy was appointed to take care of Egypt's interests in the Upper Nubian Kingdom of Kush. The ubiquitous Ahmose, son of Ibana, was present to witness the new king's triumph:

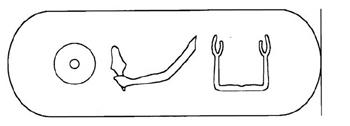

Fig. 2.4 The cartouche of King Amenhotep I

I transported the King of Upper and Lower Egypt Djeserkare [Amenhotep I], the justified, when he sailed south to Kush to make wider the borders of Egypt. His Majesty smote those Bowmen of Nubia in the midst of his army. They were brought away in a stranglehold, none escaping. The fleeing were laid low, as if they had never existed. I was at the head of the army and truly I fought. His Majesty saw my bravery. I brought away two hands to bring to his Majesty… Then I was rewarded with gold. I brought away two female captives as plunder, apart from those which I brought to his Majesty, and I was made ‘Warrior of the Ruler’.

22

Internally, there was an ambitious building programme encompassing several Upper Egyptian sites, and the arts and sciences flourished. Dying before his mother, Amenhotep I became the focus of a funerary cult at Deir el-Medina, where he was worshipped as ‘Amenhotep of the Town’, ‘Amenhotep Beloved of Amen’, or ‘Amenhotep of the Forecourt’. When she, too, flew to heaven, Ahmose Nefertari was also deified and worshipped at Deir el-Medina as patron goddess of the Theban necropolis. She eventually became ‘Mistress of the Sky’ and ‘Lady of the West’ and her cult lasted throughout the New Kingdom.

Ahmose Nefertari's forceful personality completely eclipsed that of her son's consort and sister, Queen Meritamen. Although we are told that Meritamen also bore the title of ‘God's Wife of Amen’ we know little else about this lady, beyond the fact that she did not provide her husband with a living male successor. Amenhotep I was therefore followed as king by a man whom he himself had chosen, a middle-aged general who was to become King Tuthmosis I. As the early 18th Dynasty was a time when the ruling élite formed a close-knit and well-defined group almost invariably linked by marriage, the new heir to the throne may well have been a descendant of a collateral branch of the royal family.

23

Tuthmosis himself, however, makes no claim to royal blood. His father is never named and remains a man of mystery, although it seems safe to assume that had he been of noble or royal birth Tuthmosis would have been the first to acknowledge him, while his mother was a non-royal woman named Senisenb who was never a queen and who was always given the simple title of ‘King's Mother’. Tuthmosis himself confirmed his mother's relatively humble origins when he required his loyal troops to swear an oath of loyalty on his

accession ‘by the name of His Majesty, life, health and strength, born of the Royal Mother Senisenb’. This choice of successor seems to have met with general approval and in the fullness of time Tuthmosis I became pharaoh of Egypt. The Tuthmoside era had begun.

There is some rather weak archaeological evidence to suggest that Amenhotep I may have associated himself in a co-regency with his intended successor. On the wall of the chapel of Amenhotep at Karnak, Tuthmosis I is shown dressed as a king, performing royal tasks and with his name written in the royal cartouche. If, as has been suggested, this scene was commissioned during the lifetime of Amenhotep I, there must have been two kings on the throne at the same time. Unfortunately, we have no means of knowing when the carving was made and, while it would certainly have made good sense for Amenhotep to associate himself formally with Tuthmosis, the case for a joint reign must rest unproven. It is, after all, equally possible that the building, started by Amenhotep, was finished after his death by Tuthmosis. The fact that Tuthmosis I started to count his regnal years from the death of his predecessor is of little help in determining whether or not the two shared a reign.

The tradition of the co-regency, a regular feature of 12th Dynasty reigns and one which reappears during the early 18th Dynasty, appears a strange one to those of us accustomed to seeing a single divinely appointed monarch on the throne. Joint rule must have posed many practical difficulties – how could the country be ruled by two kings at the same time? Were the royal duties performed in stereo or were they divided on some mutually agreed basis? Was there to be a ‘junior’ and a ‘senior’ king? And how was the joint reign to be dated? Egyptian

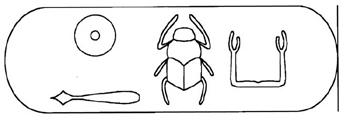

Fig. 2.5 The cartouche of King Tuthmosis I

theology decreed that the attributes of divine kingship were passed from father to son, the son becoming the living Horus at the precise moment that his dying father became the dead Osiris yet, as Gardiner has pointed out, ‘… there is no hint that the Egyptians ever felt scruples on this score. In matters of religion logic played no great part, and the assimilation or duplication of deities doubtless added a mystic charm to their theology.’

24

The question of how such a joint reign was to be dated was no trivial matter – the Egyptians always described their years with reference to the current pharaoh. We now know that there were in fact two types of co-regencies, each employing a different dating system. Where there was clearly a ‘senior’ and a more ‘junior’ king, the joint reign was dated by reference to the regnal years of the senior partner with the junior king counting his own years only from the death of his senior. Such unequal co-regencies leave very little evidence and are consequently very hard for the historian to detect. Other co-regencies, where the newest king started to count his regnal years from the beginning of the co-regency while his co-ruler continued with his own regnal years, may be viewed as a more equal partnership. However, this equality led to a certain amount of chronological confusion as each year of such a co-regency had two equally valid regnal dates, and indeed we occasionally find ‘double-dated’ texts and monuments giving the regnal years of two contemporary kings, while the anniversaries of the succession of each king created two New Year's days which were not necessarily synchronized with the third New Year's day, that of the civil calendar.

25

Given these not inconsiderable drawbacks, it is perhaps not surprising to find that double-dated co-regencies were rare during the New Kingdom.

In spite of the theological, political and dating problems posed by joint reigns, they remained a feature of Egyptian kingship. There must, therefore, have been enough compensating advantages to make a co-regency appear worthwhile. Perhaps the main advantage was that the co-regency made the intended succession absolutely clear; no one could dispute the intentions of a king who had already announced his successor. At times when the new king was not an obvious choice (for example, when there was no legitimate male heir), the co-regency must have seemed a sensible precaution which would deter any other claimant to the throne and ensure continuity of rule in a land where so

much depended on the presence of a pharaoh on the throne. The additional benefit of allowing the new king to learn the art of government while the old king eased into a semi-retirement must have been appreciated by both monarchs.

King Tuthmosis I was married to a lady named Ahmose, a popular female name in New Kingdom Egypt. There is some disagreement over the origins of this lady, with some authorities classing her as a daughter of Amenhotep I and others placing her as the daughter of Ahmose and Ahmose Nefertari and therefore a full sister of Amenhotep I. Whatever her parentage, until recently all experts were in agreement that Ahmose must have been a princess of the royal blood, and that Tuthmosis must have married her in order to make his position as king even more secure. It is relatively common for a legally dubious claimant to a throne to seek to enhance his position by marrying a close female relative of his predecessor, a match which consolidates his claim while removing any potential challenge from the children or grandchildren of the previous king. In Egypt, such political matches appear to have been standard procedure; indeed, the first pharaoh of the Archaic Period, the victorious southern King Narmer, contracted a similar marriage when he married Neith-Hotep, a northern Princess. We should therefore not be too surprised to find that Tuthmosis appeared to follow this prudent plan.

However, Queen Ahmose, who bears the title of ‘King's Sister’ (

senet nesu

) is never accorded the more important title of ‘King's Daughter’ (

sat nesu

). The Egyptians were not generally shy of recording their ranks and achievements, and this unusual reticence may therefore be an indication that Ahmose was not the daughter of a king, and by extension that she could not be either the daughter or the sister of Amenhotep I. Instead, she may actually have been the sister or half-sister of Tuthmosis I. If this is the case, we may speculate that their brother–sister marriage must have occurred after Tuthmosis's promotion to heir apparent, as such incestuous marriages are extremely rare outside the immediate royal family. This would suggest that Hatchepsut, and indeed her full brothers and sister, may have been born after Tuthmosis had become co-regent, and that Hatchepsut may therefore have been little more than twelve years old when she married her half-brother to become queen consort.