Hatchepsut: The Female Pharaoh (16 page)

Read Hatchepsut: The Female Pharaoh Online

Authors: Joyce Tyldesley

Tags: #History, #Africa, #General, #World, #Ancient

The tomb was discovered full of rubbish… this rubbish having poured into it in torrents from the mountain above. When I wrested it from the plundering Arabs I found that they had burrowed into it like rabbits, as far as the sepulchral hall… I found that they had crept down a crack extending halfway down the cleft, and there from a small ledge in the rock they had lowered themselves by a rope to the then hidden entrance of the tomb at the bottom of the cleft: a dangerous performance, but one which I myself had to imitate, though with better tackle… For anyone who suffers from vertigo it certainly was not pleasant, and though I soon overcame the sensation of the ascent I was obliged always to descend in a net.

20

Having eventually gained entrance to the tomb, and cleared it of its accumulated debris, Carter discovered that internally the tomb was similar in plan to that which Tuthmosis II had been constructing

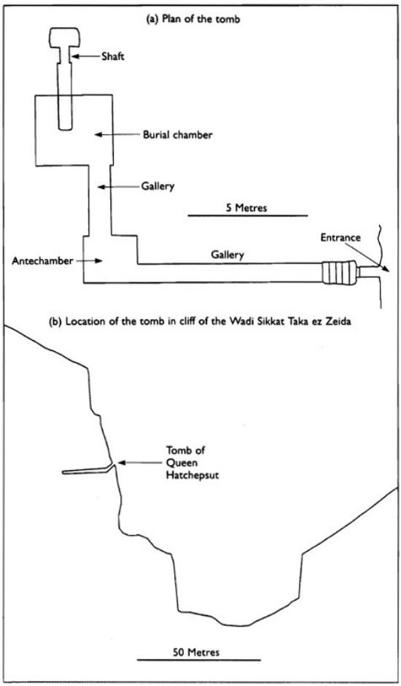

Fig. 3.5 Plan of Hatchepsut's first tomb

in the Valley of the Kings, with an entrance stairway descending to a doorway and leading in turn to a gallery, antechamber, second gallery and burial chamber. One of the descending galleries housed an impressive quartzite sarcophagus, a stone version of the massive rectangular wooden outer coffin provided for the burials of Queens Ahhotep and Ahmose Nefertari, measuring 1.99 m × 0.73 m × 0.73 m (6 ft 6 in × 2 ft 4 in × 2 ft 4 in). The lid, 0.17 m (6½ in) thick, was discovered propped against a corner of the sarcophagus. This, the first of the three magnificent sarcophagi which Hatchepsut was to commission, bore an inscription for ‘The Great Princess, great in favour and grace, Mistress of All Lands, Royal Daughter and Royal Sister, Great Royal Wife, Mistress of the Two Lands, Hatchepsut’. On the lid was a prayer to the goddess Nut, adapted from the Old Kingdom

Pyramid Texts

:

Recitation: The King's Daughter, God's Wife, King's Great Wife, Lady of the Two Lands, Hatchepsut, says ‘O my mother Nut, stretch thyself over me, that thou mayest place me among the imperishable stars which are in thee, and that I may not die.’

21

The burial shaft, cut into the floor of the chamber, was unfinished. The tomb had been abandoned before the preliminary work had been completed, and it had clearly never been used by its intended owner.

Hatchepsut bore her brother one daughter, the Princess Neferure. For a long time it was believed that a second contemporary royal princess, Meritre-Hatchepsut (often referred to as Hatchepsut II), eventual consort of Tuthmosis III and mother of Amenhotep II, was the younger daughter of Hatchepsut and Tuthmosis II, but there is no foundation for this assumption which seems to be based on nothing more concrete than the coincidence that the two ladies shared the same name. Hatchepsut herself makes no mention of a second daughter on any of her monuments while Meritre-Hatchepsut is tantalizingly silent about her parentage although, given the fact that she became a God's Wife, Great Royal Wife and Mother of the king, it seems likely that she was born a member of the immediate royal family.

Neferure, undisputed daughter of Hatchepsut and Tuthmosis II, appears suitably invisible, as we might expect of a young royal child, throughout her father's reign. However, following the death of Tuthmosis II, she starts to play an unusually prominent part in court life, suddenly appearing in public alongside her mother, the king. The little princess is now far more conspicuous than her mother was at an equally early age, and it is difficult to escape the conclusion that, while Hatchepsut's childhood was overshadowed by that of her brothers, Neferure as an only child was being groomed from an early age to play an important role in the Egyptian royal family. However, there is a big difference between training a daughter to be queen consort – for it would have been almost a foregone conclusion, given her ancestry, that Neferure would marry the next pharaoh – and raising her to become king.

To hint, as some modern historians have done, that Hatchepsut intended from the outset that her daughter would become pharaoh is to imply one of two very different views of Hatchepsut's personality. The first, the simplest and in many ways the most acceptable scenario, is that Hatchepsut was being merely practical in her assumption that Neferure might eventually inherit the throne. If Hatchepsut had realized that she herself, as queen, would not bear a son, if Tuthmosis III had died in infancy and if the immediate royal family could offer no more suitable (that is, male) candidate for the crown, she may well have been proved correct. Historical precedent would certainly have been on ‘King’ Neferure's side, as the Middle Kingdom Queen Sobeknofru had successfully claimed the throne in the absence of any more suitable male heir. In this case, we might push our speculation further by suggesting that Tuthmosis III, the son and eventual heir of Tuthmosis II, was either not born until the very end of his father's reign, or that for some reason – perhaps because of his mother's lowly birth – he was not always considered an entirely suitable heir. It would certainly have been prudent, in an age where no child could be guaranteed to live to become an adult, to ensure that as many royal children as possible were educated as future kings.

Alternatively, it has been suggested by those historians belonging to the anti-Hatchepsut camp that Hatchepsut's treatment of Neferure was the outward sign of her own personal disappointment and thwarted ambition. Hatchepsut may have grown to see the position of queen

consort and eventual queen mother as an unfulfilling and unacceptably subordinate role both for herself and her daughter. Herself the daughter and sister of a king, she had experienced years of being passed over in favour of male relations, and had no intention of seeing her much-loved daughter repeat her humiliation. She therefore planned that her daughter should upset the

status quo

and become a female pharaoh. In many respect this argument lacks conviction. We have no evidence to suggest that Hatchepsut was ever dissatisfied with her own role as consort during the reign of Tuthmosis II, although it could of course be argued that we are unlikely ever to find such evidence. More to the point, it seems unlikely that Hatchepsut, the product of a highly conservative society brought up to think in conventional gender stereotypes, would even dare to imagine that she had any chance of successfully challenging

maat

without a valid and widely acceptable reason.

From infancy, the care of the royal princess was considered to be a matter of some importance, and successive high-ranking officials laid claim to the prestigious title of royal nurse or royal tutor. In his tomb at el-Kab, Ahmose-Pennekheb proudly recalls how ‘the God's Wife repeated favours for me, the great King's Wife Maatkare, justified; I educated her eldest daughter, Neferure, justified, when she was a child at the breast’.

22

Later Senenmut, Hatchepsut's most influential courtier, became first Steward of Neferure and then royal tutor; Senenmut seems to have taken particular pride in his association with the young princess and we have several statues which show him holding Neferure in his arms, or sitting with her on his lap. When Senenmut eventually moved on to greater glories, the administrator Senimen took over the role of caring for the young princess. The extent to which Neferure was actually educated by any of her tutors is hard for us to assess. It seems very probable that most kings of Egypt could read and write, particularly those who had been taught in the harem schools, but literacy was by no means a necessity as the king had access to armies of scribes who could read and write on his behalf. If Neferure was truly being raised to inherit the throne, we might expect that she was given the education appropriate to a crown prince. In general, however, royal women were less likely than their brothers to be literate but would find this less of a disadvantage than we might suppose, thanks to the ready availability of professional scribes who could be hired as often as needed.

Given her background as the daughter and half-sister of a king, it would seem almost certain that Neferure was the intended bride of Tuthmosis III. The heir to the throne would have been the only man royal enough to marry such a well-connected girl, and she in turn would have made the most suitable mother of the next king. However, we have no record of their ever marrying, and it was Meritre-Hatchepsut rather than Neferure who was to become the mother of the subsequent pharaoh of Egypt, Amenhotep II. It is therefore surprising to find that throughout her mother's reign Neferure bore the title of ‘God's Wife’, the title which her mother had preferred as both consort and regent, and one which was normally reserved for the principal queen or queen mother. Any ‘normal’ king would be accompanied in such scenes by his wife, and here we almost certainly have the true explanation of Neferure's prominence. Hatchepsut as king needed a God's Wife to participate in the ritual aspects of her role and to ensure the preservation of

maat

. As Hatchepsut could not act simultaneously as both God's Wife and King her own daughter, herself the daughter of a king (or rather two kings) and therefore an acknowledged royal heiress, was the ideal person to fill the role and act as her mother's consort. The dismantled blocks of the Chapelle Rouge at Karnak (discussed in further detail in

Chapter 4

) include three sets of scenes in which an unnamed God's Wife is shown performing her duties during the reign of King Hatchepsut. In the absence of a more suitable candidate for the position, it seems safe to assume that the anonymous lady must be Neferure. The groups of scenes make the importance of the God's Wife clear. This was not an honorary role and, in theory at least, the God's Wife had to be present during the temple rituals. In one scene the God's Wife is shown, together with a priest, performing a ritual to destroy by burning the name of Egypt's enemies. In the second tableau she stands, both arms raised, with three priests to watch Hatchepsut present the seventeen gods of Karnak with their dinner. The final ritual shows the God's Wife leading a group of male priests to the temple pool to be purified, and then following Hatchepsut into the sanctuary where the King performs rites in front of the statue of Amen.

Neferure fades out of the limelight towards the end of her mother's reign; she is mentioned in the first tomb of Senenmut built in regnal Year 7 and appears on a stela at Serabit el-Khadim in Year 11, but then

vanishes. She is unmentioned in Senenmut's Tomb 353 dated to Year 16, and the lack of further references to the hitherto prominent princess strongly suggests that she had died and been buried in her tomb in the Wadi Sikkat Taka ez-Zeida, close to that being prepared for her mother. There is only one, inconclusive, shred of evidence which hints that Neferure may have outlived her mother and married Tuthmosis III.

23

It is possible, but by no means certain, that Neferure was originally depicted on a stela dated to the beginning of Tuthmosis III's solo reign. However, although Neferure's title of God's Wife is given, the associated name on the stela now reads ‘Satioh’. We know that Satioh was the first principal wife of Tuthmosis III, and that she never bore the title God's Wife. Is it possible that the stela, originally designed to include Neferure as the chief wife of Tuthmosis III, could have been altered after her death to show a replacement chief wife?

There is a general consensus of opinion that Tuthmosis II was not a healthy man, and that throughout his reign he was ‘hampered by a frail constitution which restricted his activities and shortened his life’.

24

His mummy, unwrapped by Maspero in 1886, was found to have been badly damaged by ancient tomb robbers. The left arm had become detached, the right arm was severed from the elbow downwards and the right leg had been completely amputated by a single axe-blow. Maspero was particularly struck by the unhealthy condition of the king's skin:

The mask on his coffin represents him with a smiling and amiable countenance, and with fine pathetic eyes which show his descent from the Pharaohs of the XVIIth dynasty… He resembles Tuthmosis I; but his features are not so marked, and are characterised by greater gentleness. He had scarcely reached the age of thirty when he fell victim to a disease of which the process of embalming could not remove the traces. The skin is scabrous in patches and covered with scars, while the upper part of the [scalp] is bald; the body is thin and somewhat shrunken, and appears to have lacked vigour and muscular power.

25

Some years later Smith was also allowed access to the mummy, and noted that:

The skin of the thorax, shoulders and arms (excluding the hands), the whole of the back, the buttocks and legs (excluding the feet) is studded with raised macules varying in size from minute points to patches a centimetre in diameter.

26

Smith concluded that the mottled patches of skin were unlikely to be the signs of disease, as similar blotches were also to be found, albeit to a lesser extent, on the mummified bodies of Tuthmosis III and Amenhotep II. He therefore decided that they must have been caused by preservative used in mummification.