Have His Carcase (54 page)

Authors: Dorothy L. Sayers

supposes are right, then MZTSXSRS is RUSQSIAT. Knock out the Q and

we’ve got RUSSIAT.

Why

couldn’t that be RUSSIA?’

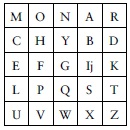

‘Why not, indeed? Let’s make it so. Write the letters down. M O N A R –

oh, Harriet!’

‘Don’t joggle!’

‘I must joggle! We’ve got the key-word. MONARCH. Wait a jiff. That

leaves three spaces before E, and we’ve only got B and D to put in. Oh, no, I

forgot! Y – dear old Y! MONARCHY! Three loud cheers! There you are! Al

done by kindness! There! There’s your square complete. And joly pretty it

looks, I must say.’

‘Oh, Peter! How marvelous! Let’s dance or do something.’

‘Nonsense! Let’s get on with the job. None of your frivoling now. Start

away. PR BF XA LI MK MG BF FY MG TS QJ – and let’s get to the

bottom of this BF FY business, once and for al. I’l read out the diagonals and

you write ’em down.’

‘Very wel. T – O – H – I – “To His Serene” – can that be right?’

‘It’s English. Hurry up – let’s get BFFY.’

‘ “To His Serene Highness” – Peter! what

is

al this about?’

Lord Peter turned pale.

‘My God!’ he exclaimed, melodramaticaly, ‘can it be? Have we been wrong

and the preposterous Mrs Weldon right? Shal I be reduced, at my time of life,

to hunting for a Bolshevik gang? Read on!’

XXIX

THE EVIDENCE OF THE LETTER

‘In one word hear, what soon they all shall hear:

A king’s a man, and I will be no man

Unless I am a king.’

Death’s Jest-Book

Friday, 3 July

‘To His Serene Highness Grand-Duke Pavlo Alexeivitch heir to the throne of the

Romanovs.

‘Papers entrusted to us by your Highness now thoroughly examined and marriage

of your illustrious ancestress to Tsar Nicholas First proved beyond doubt.’

Harriet paused. ‘What does that mean?’

‘God knows. Nicholas I was no saint, but I didn’t think he ever

married

anybody except Charlotte-Louise of Prussia. Who the deuce is Paul Alexis’

ilustrious ancestress?’

Harriet shook her head and went on reading.

‘All is in readiness. Your people groaning under oppression of brutal Soviets

eagerly welcome return of imperial rule to Holy Russia.’

Wimsey shook his head.

‘If so, that’s one in the eye for my Socialist friends. I was told only the other

day that Russian Communism was doing itself proud and that the Russian

standard of living, measured in boot-consumption, had risen from zero to one

pair of boots in three years per head of population. Stil, there may be Russians

so benighted as not to be content with that state of things.’

‘Alexis did always say he was of noble birth, didn’t he?’

‘He did, and apparently found somebody to believe him. Carry on.’

‘Treaty with Poland happily concluded. Money and arms at your disposal. Your

‘Treaty with Poland happily concluded. Money and arms at your disposal. Your

presence alone needed.’

‘Oho!’ said Wimsey. ‘Now we’re coming to it. Hence the passport and the

three hundred gold sovereigns.’

‘Spies at work. Use caution. Burn all papers all clues to identity.’

‘He obeyed that bit al right, blow him!’ interjected Wimsey. ‘It looks as though

we were now getting down to brass tacks.’

‘On Thursday 18 June take train reaching Darley Halt ten-fifteen walk by coast-

road to Flat-Iron Rock. There await Rider from the Sea who brings instruction for

your journey to Warsaw. The word is Empire.’

‘The Rider from the Sea? Good gracious! Does that mean that Weldon – that

the mare – that –?’

‘Read on. Perhaps Weldon is the hero of the piece instead of the vilain. But

if so, why didn’t he tel us about it?’

Harriet read on.

‘Bring this paper with you. Silence, secrecy imperative. Boris.’

‘Wel!’ said Wimsey. ‘In al this case, from beginning to end, I only seem to

have got one thing right. I said that the letter would contain the words: “Bring

this paper with you” and it does. But the rest of it beats me. “Pavlo Alexeivitch,

heir to the throne of the Romanovs.” Can your land-lady produce anything in

the shape of a drink?’

After an interval for refreshment, Wimsey hitched his chair closer to the table

and sat staring at the decoded message.

‘Now,’ he said, ‘let’s get this straight. One thing is certain. This is the letter

that brought Paul Alexis to the Flat-Iron. Boris sent it, whoever he is. Now, is

Boris a friend or an enemy?’

He rumpled his hair wildly, and went on, speaking slowly.

‘The first thing one is inclined to think is that Boris was a friend and that the

Bolshevik spies mentioned in the letter got to the Flat-Iron before he did and

murdered Alexis and possibly Boris as wel. In that case, what about Weldon’s

mare? Did she bring the “Rider from the Sea” to his appointment? And was

Weldon the rider, and the imperialist friend of Alexis? It’s quite possible,

because – no, it isn’t. That’s funny, if you like.’

‘What?’

‘I was going to say, that in that case Weldon could have ridden to the Flat-

Iron at twelve o’clock, when Mrs Polock heard the sound of hoofs. But he

didn’t. He was in Wilvercombe. But somebody else may have done so – some

friend to whom Weldon lent the mare.’

‘Then how did the murderer get there?’

‘He walked through the water and escaped the same way, after hiding in the

niche til you had gone. It was only while Weldon or Bright or Perkins was

supposed to be the murderer that the time-scheme presented any real difficulty.

But who was the Rider from the Sea? Why does he not come forward and say:

“I had an appointment with this man. I saw him alive at such a time?” ’

‘Why, because he is afraid that the man who murdered Alexis wil murder

him too. But it’s al very confusing. We’ve now got two unknown people to

look for instead of one: the Rider from the Sea, who stole the mare and was at

the Flat-Iron about midday, and the murderer, who was there at two o’clock.’

‘Yes. How difficult it al is. At any rate, al this explains Weldon and Perkins.

Naturaly they said nothing about the mare, because she had gone and come

again long before either of them was at the camping-ground. Wait a moment,

though; that’s odd. How did the Rider from the Sea know that Weldon was

going to be away in Wilvercombe that morning? It seems to have been pure

accident.’

‘Perhaps the Rider damaged Weldon’s car on purpose.’

‘Yes, but even then, how could he be sure that Weldon would go away? On

the face of it, it was far more likely that Weldon would be there, tinkering with

his car.’

‘Suppose he knew that Weldon meant to go to Wilvercombe that morning in

any case. Then the damaged H.T. lead would be pure bad luck for him, and the

fact that Weldon did, after al, get to Wilvercombe, a bit of compensating good

luck.’

‘And how did he know about Weldon’s plans?’

‘Possibly he knew nothing about Weldon at al. Weldon only arrived at

Darley on the Tuesday, and al this business was planned long before that, as

the date of the letter shows. Possibly whoever it was was horrified to find

Weldon encamped in Hinks’s Lane and frightfuly relieved to see him barge off

on the Thursday morning.’

Wimsey shook his head.

‘Talk about coincidence! Wel, maybe so. Now let’s go on and see what

happened. The Rider made the appointment with Alexis, who would get to the

Flat-Iron about 11.45. The Rider met him there, and gave him his instructions –

verbaly, we may suppose. He then rode back to Darley, loosed the mare and

went about his business. Right. The whole thing may have been over by 12.30

or 12.45, and it must have been over by 1.30, or Weldon would have seen him

on his return. Meanwhile, what does Alexis do? Instead of getting up and going

about

his

business, he sits peacefuly on the rock, waiting for someone to come

along and murder him at two o’clock!’

‘He may have been told to sit on a bit, so as not to leave at the same time as

the Rider. Or here’s a better idea. When the Rider has gone, Alexis waits for a

little bit – say five minutes – at any rate, til his friend is wel out of reach. Then

up pops the murderer from the niche in the rock, where he has been

eavesdropping, and has an interview with Alexis. At two o’clock, the interview

ends in murder. Then I turn up, and the murderer pops back into hiding. How’s

that? The murderer didn’t show himself while the Rider was there, because he

didn’t feel equal to tackling two men at once.’

‘That seems to cover the facts. I only wonder, though, that he didn’t murder

you too, while he was about it.’

‘That would make it look much less like suicide.’

‘Very true. But how was it you didn’t see these two people talking

animatedly on the Flat-Iron when you arrived and looked over the cliff at one

o’clock?’

‘Goodness knows! But if the murderer was standing on the seaward side of

the rock – or if they both were – I shouldn’t have seen anything. And they may

have been, because it was quite low tide then, and the sand would have been

dry.’

‘Yes, so it would. And as the discussion prolonged itself, they saw the tide

turn, so they scrambled up on to the rock to keep their feet dry. That would be

while you were asleep. But I wonder you didn’t hear the chattage and talkery

going on while you were having your lunch. Voices carry wel by the sea-

shore.’

‘Perhaps they heard me scrambling down the cliff and shut up.’

‘Perhaps. And then the murderer, knowing that you were there, deliberately

committed his murder under your very nose, so to speak.’

‘He may have thought I had gone. He knew I couldn’t see him at the

moment, because he couldn’t see me.’

‘And Alexis yeled, and you woke up, and he had to hide.’

‘That’s about it. It seems to hang together reasonably wel. And that means

we’ve got to look for a quite new murderer who had an opportunity of knowing

about the appointment between Boris and Alexis. And,’ added Harriet,

hopefuly, ‘it needn’t be a Bolshevik. It might be somebody with a private

motive for doing away with Alexis. How about the da Soto gentleman who got

the reversion of Leila Garland? Leila may have told him some nasty story about

Alexis.’

Wimsey was silent; his thoughts seemed to be wandering. Presently he said:

‘Yes. Only we happen to know that da Soto was playing at the Winter

Gardens al that time. But now I want to look at the thing from a quite different

point of view. What about this letter? Is it genuine? It’s written on ordinary sort

of paper, without a water-mark, which might come from anywhere, so that

proves nothing, but if it realy comes from a foreign gentleman of the name of

Boris, why is it written in English? Surely Russian would be safer and more

likely, if Boris was realy a Russian imperialist. Then again – al that opening

stuff about brutal Soviets and Holy Russia is so vague and sketchy. Does it

look like the letter of a serious conspirator doing a real job of work? No names

mentioned; no details about the Treaty with Poland; and, on the other hand,

endless wasted words about an “ilustrious ancestress” and “His Serene

Highness”. It doesn’t ring true. It doesn’t look like business. It looks like

somebody with a very sketchy idea of the way revolutions realy work, trying to

flatter that poor boob’s monomania about his birth.’

‘I’l tel you what it does look like,’ said Harriet. ‘It’s like the kind of thing I

should put into a detective story if I didn’t know a thing about Russia and didn’t

care much, and only wanted to give a general idea that somebody was a

conspirator.’

‘That’s it!’ said Wimsey. ‘You’re absolutely right. It might have come

straight out of one of those Ruritanian romances that Alexis was so fond of.’

‘Of course – and now we know why he was fond of them. No wonder!

They were al part of the mania. I suppose we ought to have guessed al that.’