He: (Shey) (Modern Classics (Penguin))

Read He: (Shey) (Modern Classics (Penguin)) Online

Authors: Rabindranath Tagore

Contents

Rabindranath Tagore wrote He (Shey) to satisfy his nine-year-old granddaughter’s incessant demands for stories. Even as Tagore began to create his grand fantasy, he planned a story that had no end, and to keep the tales spinning he employed the help of ‘Shey’ (He), a ‘man constituted entirely of words’ and rather talented at concocting tall tales.

So we enter the delightful world of Shey’s extraordinary adventures. In it we encounter a bizarre cast of characters (the ganja-addict Patu whose body He inhabits after losing his own in a pond, a misdirected jackal who aspires to be human, the snuff-sniffing scientists of Hoonhau Island and the New Age poets of the Hoi! Polloi Club dedicated to the cause of tunelessness); grotesque creatures like the Gandishandung and Bell-Ears; comic caricatures of contemporary figures and events, as well as mythological heroes and deities—all brought to life through a sparkling play of words and illustrations in Tagore’s unique style.

In this first-ever complete translation of

Shey

, including Tagore’s delightful nonsense verse, Aparna Chaudhuri brilliantly captures the spirit and flavour of the original.

Translated by APARNA CHAUDHURI

‘On reading [

Shey

], I find it is not just for children but for the eternal child. Those for whom you have written it will never cease to be children’

Banaphul, in a letter to Tagore

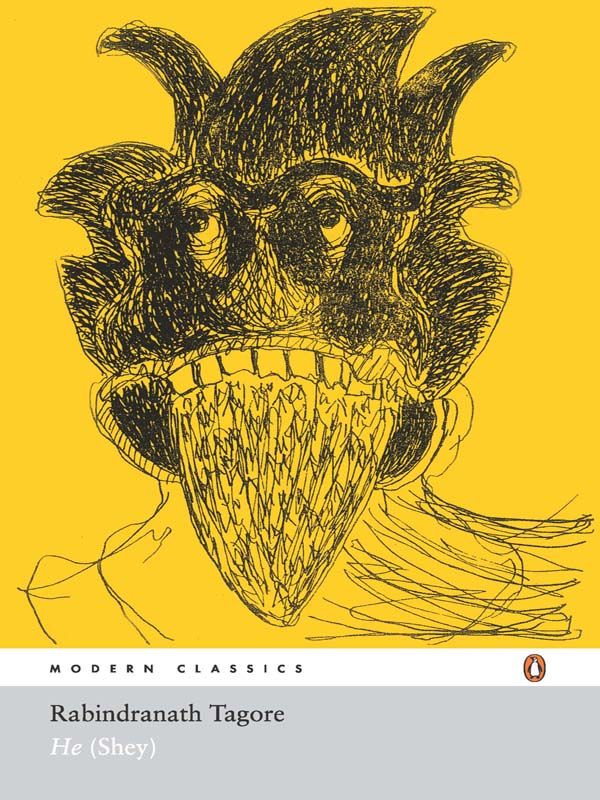

Cover illustration by Rabindranath Tagore

MODERN CLASSICS

Fiction/Translation

PENGUIN BOOKS

HE

RABINDRANATH TAGORE was born in 1861. He was the fourteenth child of Debendranath Tagore, head of the Brahmo Samaj. The family house at Jorasanko was a hive of cultural and intellectual activity and Tagore started writing at an early age. In the 1890s he lived in rural East Bengal, managing family estates. He was involved in the Swadeshi campaign against the British in the early 1900s. In 1912 he travelled to England with

Gitanjali

, a collection of English poems, and won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1913. Tagore was knighted in 1915, an honour he repudiated in 1919 after the Jallianwala Bagh massacre. In the 1920s and 1930s he lectured extensively in America, Europe, the Far East and Middle East. Proceeds from these and from his Western publications went to Visva-Bharati, his school and university at Shantiniketan. Tagore was a prolific writer; his works include poems, novels, plays, short stories, essays and songs. Late in his life Tagore took up painting, exhibiting in Moscow, Berlin, Paris, London and New York. He died in 1941.

APARNA CHAUDHURI is in her final year at Calcutta Girls’ High School.

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Books India Pvt. Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park,

New Delhi 110 017, India

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014,

USA

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto,

Ontario, M4P 2Y3, Canada (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of

Penguin Books Ltd)

Penguin Group (Australia), 707 Collins Street, Melbourne, Victoria 3008, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)

Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, Auckland 0632, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)

Penguin Group (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, Block D, Rosebank Office Park, 181 Jan Smuts Avenue, Parktown North,

Johannesburg 2193, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

First published by Penguin Books India 2007

Translation and Translator’s Note copyright © Aparna Chaudhuri 2007

Introduction copyright © Sankha Ghosh 2007

Illustrations by Rabindranath Tagore

All rights reserved

ISBN: 978-0-14310-209-0

This Digital Edition published in 2010.

e-ISBN: 978-8-18475-095-9

Digital conversion prepared by DK Digital Media, India.

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or

otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the

publisher’s prior written consent in any form of binding or cover other than

that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this

condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser and without limiting

the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be

reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted in

any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording

or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright

owner and the above-mentioned publisher of this book.

A child comes to me and commands me to tell her a story. I tell her of a tiger which is disgusted with the black stripes on its body and comes to my frightened servant demanding a piece of soap. The story gives my little audience immense pleasure, the pleasure of a vision, and her mind cries out, ‘It is here, for I see!’ She knows a tiger in the book of natural history, but she can see the tiger in the story of mine.

—Rabindranath Tagore,

The Religion of Man

I first read

Shey

1

when I was ten years old. In retrospect, I think the idea of translating it grew out of a desire to enter more actively into the text and the characters; at the time, it was just something to keep me occupied during a long summer vacation. I approached the translation in no very purposeful spirit—the first draft contained more doodles than writing and was frequently buried under novels, school work and anything else that happened to engage my attention. Done in occasional spurts, the work took longer than it might otherwise have. I changed my mind about almost every sentence, and when, some years later, I completed the translation, I could hardly remember what it was like when I began.

Both while reading

Shey

and translating it I had to keep in mind that the story was originally told and not written (at least, that is the impression sought to be conveyed). Like all told stories, it evolved through its telling—the ideas are dependent on the words, just as the words are fitted to the ideas. As a reader, I enjoyed this exchange between word and meaning—as a translator, I recognized it as a problem. The hero of Tagore’s story is introduced as ‘a man constituted entirely of words’. As a translator, I had to create the same man in a different idiom—to tell the same story, but in different words. This search for different words led me to the accidental discovery of many different meanings of the original words; while exploring the linguistic possibility of translation, I was led also to explore different analytic and imaginative possibilities inherent in the original work. Not all these possibilities can be fulfilled, or even conveyed, through translation—they can, however, considerably enrich one’s reading of

Shey

. They also make translation of a work like this, more than of any other kind, an imaginative rather than a purely linguistic exercise. If

Shey

is to make sense (or nonsense) in any language other than its original Bengali, merely finding the closest linguistic equivalents in that language is patently not enough to achieve that aim.

At the same time,

Shey

is very much a modern fantasy, part of a universal more-than-real. Like Carroll in

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland

or Antoine de Saint-Exupéry in

The Little Prince

, Tagore taps a vein of the purest whimsy that makes

Shey

a fantasy on the grand scale. Even the local or regional references retain their effect in translation, because they have become components of a fantasy world. At the same time, the colloquial language, the frequent play on words, and the caricatures of the heroes and deities of Indian mythology cannot quite keep their original flavour. I only hope this does not materially lessen their fun.

Happily, the sketches Tagore drew to illustrate

Shey

require no translation, and, therefore, run none of the risks of the text. Yet, at best, they only aid the imagination of the reader, who remains perfectly free to picture Shiburam or Puttulal or the Gandishandung as he or she pleases. In the last chapter, the writer discusses the ‘Age of Truth’ with young Sukumar and Pupe, when people will know by being, rather than touching or seeing:

Sukumar spoke. ‘It’s fun to think of you spreading over trees and brooks and becoming part of them. Do you think the Age of Truth will ever come?’

‘Till it does, we have paintings and poems. They are wonderful paths down which you can forget yourself and become other things.’

Perhaps the sketches are only the story-maker’s way of becoming the story.

This idea of ‘becoming the story’ is central to

Shey

, a story named after its hero, a man who bears no more distinguished a name than the Bengali third person pronoun (which I have translated as ‘He’). We are told that He helps the writer to make up the story: ‘I employed another man to help me, and you will know more about him later.’ Yet He is undeniably part of the story himself. The story-creator becomes the story’s most integral element—a truth behind all stories, but seldom so apparent as in

Shey

. So that the story should include all possible elements, the story-creator does not possess the distinction of a name. His identity and character remain undefined, for to define them would be to limit them—to include him in the unmysterious intimacy of ‘youand-me’ when his function is to represent the unknown and exciting ‘them’. The ordinary thus becomes the extraordinary, and the ordinary man a creature of untrammelled, whimsical fantasy.

It is this differently fantastic quality that makes translating

Shey

difficult. The language, in itself, is simple, the style easy and conversational, the incidents amusing, even if the ideas, sometimes quite visionary, may seem strange material for a story intended for a nine-year-old. The later episodes give narrative expression to Tagore’s thoughts on education, ethics, philosophy and similar subjects that one would not have thought conducive to storytelling. But we must remember that ‘in this story of mine, there is no trace of what people usually call a story’. Instead, the very process of story-making is visible and active and, indeed, what the story is really about.

Over five years, as the translation progressed, I grew closer to the story. In fact, I grew with it—or, at any rate, with the person it was originally intended for, Tagore’s granddaughter, Nandini (Pupe), the adopted daughter of his son Rathindranath. The first stories about He are, therefore, closer to young Pupe’s experience of people and their familiar activities. The ‘Shey’ of the first stories is, in the writer’s own words, ‘a very ordinary man. He eats, sleeps, goes to the office and is fond of the cinema. His story lies in what everyone does every day.’ No sooner does he enter the story than he makes the endearing confession that he is very hungry, and, as Tagore himself points out, it is easy to make friends with a hungry man. All elements of conventional fantasy are strongly suppressed—there is nothing wonderful or magical about this man, and yet he is to help create a story ‘about something quite extraordinary…without head or tail, rhyme or reason, sum or substance, just as we please’. Obviously, the idea is to rearrange the elements of ordinary reality into an extraordinary expression of the more-than-real. It is this more-than-real that we actually experience— Pupe asking for a story ‘sees’ the tiger in it because the tiger is part of the more-than-real.