He Wanted the Moon (22 page)

Read He Wanted the Moon Online

Authors: Mimi Baird,Eve Claxton

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Personal Memoirs, #Psychology, #Psychopathology, #Bipolar Disorder, #Medical

“Even after the lobotomy, he still got into trouble,” Philip remembered, “especially if he drank. I’d be called out to rescue him from barroom fights or from the police station.”

I sensed that, just as my uncle had been waiting for me to reply to his letters, he had been waiting to tell me my father’s story.

“Maybe there’s still some way I can make amends,” I said, rather helplessly.

Soon, he got up to leave. After we hugged goodbye, he offered me one last piece of information.

“Your father was writing a book,” he said, scrawling a number on a paper napkin.

“It’s your cousin’s number,” he explained. “My son Randy. He has the manuscript. Call him.”

I walked Philip out to his car and watched him drive away, holding my cousin’s number in my hand.

Later that evening, after my duties at the conference were completed and I was back in my hotel room, I dialed my cousin Randy’s number. He answered and I introduced myself. We’d never met, never as much as spoken, and yet for the duration of the conversation, we chatted easily and warmly, perhaps both trying to make up for lost time. I learned that Randy lived in Austin. Over the next two days, we spoke on the telephone as often as we could, catching up on family matters on both sides. Eventually, I brought up the subject of the manuscript.

Randy confirmed that he had rescued it from his father’s house a few years back.

“My father and mother didn’t want it. There used to be a typed version, but that disappeared a long time ago.”

The manuscript was sitting in an old briefcase in his garage.

The day before I left Dallas, my cousin telephoned to let me know he had spoken with his wife, Karen. They both felt the manuscript belonged with me.

Several weeks later, I returned home from work to find the large carton on my doorstep with a return address in Austin. I called Texas the next day.

“We’re so very happy,” Randy’s wife, Karen, told me. “At last, they’re where they belong. Perry’s little girl has his papers. We’ve only been the caretakers.”

The pages of my father’s manuscript were completely out of sequence. I did my best to make sense of his words. On one page he was writing about having breakfast at the Ritz. On the next he was being violently restrained by hospital guards. If these pages held the key to the mystery of my father, they weren’t going to give up their secrets easily.

I tried to match them into some kind of order, glancing at each line and looking for key words to group the writing according to subject. Much of the writing was clearly about his confinement in Westborough. I learned to look for the names of the various wards where he had been kept, then evidence of his transfer to Baldpate. I recognized names of old family friends; my mother’s name, Gretta, appeared frequently. I became familiar with sequences of events and made piles of paper, according to the names of people, events, and places.

My father’s handwriting was another guide. On some pages the script was meticulously placed, with many straight lines on each page. In other instances, his handwriting became large and increasingly irregular, the background covered with dark smudges.

In the coming weeks, I lived with the papers still stacked in their piles around my kitchen as I continued to rearrange them according to a tentative timeline. The process was complicated by the fact that my father often drafted the same passage more than once, in slightly differing versions. I kept working, trying to restore the manuscript to its intended order. I was constantly hunting for clues to help me reassemble the story, never knowing what I might find next.

One day, reading through pages, I saw a word I’d never noticed before.

Mimi.

I read the entire page. My father was writing about staying at the Ritz Hotel. My mother arrived at his room with my sister and me in tow. She wouldn’t sit down and got ready to leave almost immediately. Then I spoke:

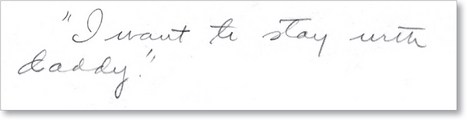

It wasn’t until I saw these words that the events of the manuscript became entirely real to me. I had been there. I had a voice. I had wanted to stay with my father.

Once the pages were in some kind of order, I began typing up his words. Initially I struggled to decipher his handwriting, but before long, I became familiar with the shape of his b’s, his l’s, his f’s. Just as I became accustomed to the contours of his letters, I also became better at detecting the levels of his sanity. For entire pages, he appeared to be completely in control of his mind. He wrote as a man of science, observing the scene as if he were a doctor visiting the hospital, rather than a patient being held there. His handwriting in these passages was orderly and regular. Then, suddenly, it would become expansive, out of control, when his grip on his sanity was slipping. Then pages and pages of visions and delusions, his script slanting to the right, the handwriting ballooning, as the urgency to get his message down on the page superseded any other concern.

After some weeks of working on the manuscript, I was handling the onionskin pages so much that I feared that they would become damaged. The pages were delicate, and were written on with pencil that smudged easily. I felt it was my great responsibility to protect my father’s words. The chances of his manuscript surviving were so slim, and yet it had ended up with my uncle in Dallas, then with my cousin in Austin, and now—so many years later—with me in Vermont. I was the caretaker now.

I purchased a box of clear, acid-free folders. That evening, I sat in my living room, sliding the pages of the manuscript inside the folders, one at a time. I was so absorbed in my task that I didn’t notice my fingers becoming blackened by the pencil from the pages. Only when I was finished did I see that my fingertips were darkened with lead.

I turned my palms up and held them before my eyes, transfixed. The thought went through my head:

My father put this lead on these papers, now it has come away on my hands.

The connection I’d always felt between us was tangible.

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN

It was clear that my father was writing about the events of 1944, the last year I’d lived with him. Emerging before me was the story of what had happened to him during those first months of his absence. Although my father’s descriptions of his time in the hospital were horrifying to read, my work was spurred on by a sense of duty. As I typed each sentence, watching the words appear on the computer screen, it was further proof that he had existed.

As I tried to absorb the meaning of his experiences, instinctively, I turned to books for help and guidance. What did it even mean that my father was “manic”? I found a copy of

The Bell Jar

and read Sylvia Plath’s novelized account of her breakdown and electric shock treatment. I read psychiatrist Kay Redfield Jamison’s

An Unquiet Mind,

about her own experiences of manic depression. I read William Styron’s startling memoir of his descent into madness,

Darkness Visible.

Over the next few months, I read as many books on mental illness and manic depression as I could find.

I kept a notebook and created page after page of quotes, looking for clues with which to plot some kind of map. I became a student of the condition, its violent and disruptive mood swings, the intense highs followed by the terrifying lows. I came to understand that, despite the menace of the disorder, manic depression is often closely allied with genius. Many of our greatest artists have been sufferers, “touched with fire,” as Jamison has written of Lord Byron, Vincent van Gogh, Virginia Woolf, and Ernest Hemingway, among many others.

The work progressed slowly. My inclination was to conduct my research a little at a time. The material I was uncovering was so unsettling that after all these years of not knowing, each discovery had to be assimilated slowly, piece by piece.

I found other traces of him, beyond the manuscript. There was the pink cloth-covered baby book where my mother recorded the small milestones of my early years, pages that are filled with references to me with my father. My mother writes that the first time I put words together in a sentence, it was to ask, “Where’s Daddy?” At the age of three, it is noted, I’d sit on my father’s lap while he read to me his favorite poems from

The Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám.

Before long, I could quote the first lines back to him: “Awake! For morning in the bowl of night has flung the stone that puts the stars to flight.”

Somewhere in my house, I knew, there was a cache of albums containing photographs and letters of his, given to me by my mother. I was a teenager when I’d first inherited them, and I had dismissed them as relics. Now I felt certain they could help me become a better student of my father’s life. I eventually located two albums tucked away in the back of one of my bookcases. The first was his baby book, its delicately worn, light blue leather covers embossed with gold. Inside, each page was decorated in the Victorian style, with golden curlicues, and images of flowers and baby faces. I found sepia studio photographs of father as a handsome toddler in overalls, his hair a mass of shining curls. In careful, steady script, my grandmother had noted the date of his first smile, his first steps, his first word. She had even preserved a lock of his baby hair. I tentatively ran my finger over the soft and glossy strands, marveling at their survival.

A second album kept by my grandmother contained my father’s school reports and photographs of him as a schoolboy. There were high school newspaper clippings indicating his many academic achievements. One article reported that he was “highly motivated and always looking toward the next goal at top speed.” He played football and was elected president of his senior class.

A letter, from 1921, contained news that he had been accepted to the University of Texas. The next letter confirmed that, after only the first semester, he had made the college honor roll. The following year, he wrote home to tell his parents he had been given a coveted assistantship by the chemistry department, and that he wished to take it, to “put me in a better position to be elected to Phi Beta Kapa in the fall.” He graduated that year summa cum laude, having completed the university’s four-year curriculum in three years. I imagined my grandmother’s pride as she received these letters, each one signed, affectionately, “Perry Boy.”