He Wanted the Moon (21 page)

Read He Wanted the Moon Online

Authors: Mimi Baird,Eve Claxton

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Personal Memoirs, #Psychology, #Psychopathology, #Bipolar Disorder, #Medical

After my stepfather passed away, and the Woodstock summer house was sold, I moved to that same Vermont village, a place I had always loved. It was 1979. My children were teenagers, and I had decided to return to work. I applied for a job at the prominent teaching hospital across the Connecticut River in New Hampshire, where I started in an entry-level secretarial job. Some months later, I was hired as the office manager in the department of plastic surgery.

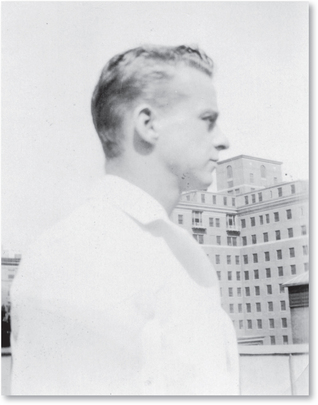

During the move to Vermont, as I packed up my possessions, I came across a box of my father’s belongings that my mother had given me when I went to college. These included some of his old books, photograph albums, and other mementoes, including two silver Paul Revere bowls my father had inscribed to celebrate his riding victories and a gold pin he had given my mother as a present. In the same box were two tin canisters of home movies marked “Perry/Gretta wedding, 1931.” With the holidays approaching, I decided to have the old film converted to VCR format, so I could give my mother the video for Christmas. I assumed the wedding film would be a nice surprise for her and might prompt some much-needed discussion between us.

Before I put the videotape in the mail, I sat in my living room to watch it. The grainy, black-and-white footage clearly showed my father and mother on their wedding day. They were standing next to one another in the receiving line against a dark background, from which their figures seemed to emerge like ghosts. My girlish mother was giddy with love and excitement. My father was tall and proud, if a little dazed. Toward the end of the video, my father bent down to give my mother a long, lingering kiss. I caught my breath. Later that day, I put the tape in a box and mailed it to my mother with great anticipation. I told my family members who would be with her on Christmas day not to reveal the contents of the tape until it began to play in the video machine.

I learned later that when my mother realized it was her wedding footage, she got up and left the room. No further mention of the tape was ever made. After this episode, I resolved never to bring up my father’s name in my mother’s presence again.

It was another ten years before I heard anyone speak of him. I continued my work at the hospital, surrounded by doctors and nurses each day, feeling a great sense of purpose in my job and appreciation for the medical environment. Then, one bright fall day in October 1991, I was scheduled to attend an opening event at our new hospital building. We had just moved in and were celebrating.

The day of the reception, I was in good spirits. I’d been out of the office for a few weeks, and so spent most of that afternoon catching up with my colleagues on the latest news from around the department. Later, I went over to speak to the guest of honor, a pioneering plastic surgeon named Dr. Radford Tanzer, after whom our new space was being named. I had worked with Dr. Tanzer for a time and had always admired him. He was now in his mid-eighties, and had the same compassionate and intelligent eyes that must have reassured many generations of patients.

During the course of our brief conversation, I mentioned to Dr. Tanzer that my father had been a doctor.

“What was your father’s name?” the surgeon asked.

“Perry Baird,” I replied.

Dr. Tanzer looked at me and paused.

“I knew your father,” he said quietly. “We were at Harvard Medical School together.”

The noise of the party seemed to ebb away in the wake of his words.

“I graduated the year after him, in 1929,” Dr. Tanzer went on. “We both attended lectures at the St. Botolph’s Club in Boston.”

It was the first time in my life

anyone

had spoken to me about my father in this way, as if he were an actual person, someone who went to Harvard, attended lectures at a club, and who

knew

people. Moments later, Dr. Tanzer was led away to speak with another party guest. I wasn’t able to ask him for any more information. Nonetheless, the effect of this short exchange on my life was profound: it validated my feeling that something significant was missing from my understanding of my early years.

The following Monday, I told another surgeon at the hospital, Dr. Morain, about the extraordinary coincidence. Dr. Morain asked me some questions, and I shared with him the very little I knew. Although my mother had always been more or less mute on the subject of her first husband, she had once told me that Dr. Walter B. Cannon was one of my father’s mentors. Dr. Morain responded that Dr. Cannon was one of the most important physiologists of the twentieth century.

A week later, Dr. Morain walked into my office, proudly holding a large manila envelope in his hands. He explained that he had been in Boston that weekend for a meeting and had decided to look in Harvard Medical School’s Countway Library of Medicine for any trace of my father. In the Walter B. Cannon archive, he had found a cache of my father’s letters to Dr. Cannon and copies of Dr. Cannon’s replies. Incredibly, the elderly lady librarian—about to retire—remembered my father and refused to charge for copying the file. I thanked Dr. Morain profusely.

Later that evening, I sat leafing through the many dozens of pages inside the envelope. Most of the correspondence was typewritten, but some of the letters were in my father’s handwriting, a large looping script. As I flipped from page to page, my eyes froze at one of the letterheads: 32 Clovelly Road, Chestnut Hill—the little white clapboard where I’d lived with my father and mother all those years ago.

I imagined my father sitting there at his writing desk in the house, the promising young doctor corresponding with one of the most famous physicians of the times. The earliest letters were written in 1928, during the period when my father had been a research assistant to Dr. Cannon. The two men discussed my father’s career, the appointments he should seek, and how he should move forward with his work.

Throughout the letters, I found repeated mention of Dr. James Howard Means, Chief of Medical Services at Massachusetts General Hospital. So I decided to visit Harvard’s Countway Library to see if Dr. Means’s archive might hold further letters from my father. The library is housed in a modern concrete structure on the outskirts of Boston, and as I walked into its large entry area, I was struck by the quiet solemnity of the place. I placed my request with the librarian and waited, as she disappeared behind two large wooden doors. Before long, she returned with a large folder of correspondence between my father and Dr. Means. I sat at one of the long wooden tables, alongside students and researchers, running my eyes across page after page. The letters spanned the early 1920s to the late 1940s. As far as I could ascertain, Dr. Means’s tone was very similar to that of Dr. Cannon: warm, friendly, and encouraging to his younger protégé.

“A man of the finest type of character,” Dr. Means wrote of my father in a letter of recommendation from 1933, “upright and sincere in every way, unselfish, brilliant and delightful, very loyal to his friends and principles. His integrity is beyond question. There is no doubt whatever but that Dr. Baird is an internist of superior ability.”

As I read, shadows from the afternoon light rippled across the pages. My father’s story was emerging from the silence.

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN

The discovery of the letters emboldened me. Some months after that, I was scheduled to attend a plastic surgery conference in Dallas, Texas, for my work. I decided that while I was there, I would look up my uncle Philip, my father’s brother. I had no information as to his whereabouts except that he lived in Dallas. As soon as I arrived at my hotel, I opened up the telephone book and looked for his name, fearing I would lose my nerve if I didn’t call right away. There were three Philip Bairds listed. I quickly dialed one of the numbers. A woman answered. No, she had never heard of me. I dialed the second number. A man who evidently was not my uncle answered and I hung up quickly. I was about to give up, but instead decided to try the last number.

“Hello,” came the voice from the other end of the line. A slow Texas “hello” with the “o” drawn out. I recognized his tone immediately.

“Hello, this is Mimi Baird,” I announced.

My uncle’s response was immediate: “Why didn’t you write back?”

I felt a pang of shame. When I was a child, Uncle Philip had written me a number of letters. I had taped them to the inside of my closet door, the secret place where I stored my treasures. They were extremely precious to me, as one of my only connections to my father. I’d just never known how to respond, and so they had always gone unanswered. My uncle had been waiting for a reply for over forty years.

I told him, truthfully, that I didn’t know why, I just never felt able to write.

“I was so young,” I told him. “I wish I had.”

We agreed to meet the next day.

Philip came to my hotel. As I waited for him in the foyer, I tried to picture him. We must have met at my father’s funeral, but I couldn’t recall his face. Would he look like my father? After a few minutes, an older man, rather disheveled, wearing white baggy shorts and a faded blue sports shirt, appeared on the other side of the lobby. In the back of my mind I remembered that Uncle Philip had played tennis. I stood up and walked toward him.

“Uncle Philip?” I asked.

He immediately enfolded me in a hug.

We went to take a seat in the little café next to the lobby. Philip sat down. It was clear he was uninterested in polite chitchat.

“Your mother neglected her responsibilities as a wife,” he told me, his face folding into a frown. “She deserted your father.”

Despite my own reservations about my mother’s actions, I felt myself wanting to leap to her defense. I knew that my great-aunt Martha had contributed a considerable amount of money for my father to stay in a private mental institution. I offered this information to Philip, noting that my mother had two young children to think about.

“We were the ones who had to pick up the pieces after your mother divorced him,” he responded sternly. “Everything fell to us.”

Philip explained that he and his wife—along with my father’s elderly parents—shouldered the burden of caring for my father.

“Your father had a lobotomy,” Philip told me. “After that, he could barely tie his own shoelaces. We had to do everything for him. Brush his teeth, buckle his belt. He was never the same.”

I remembered hearing the adults around me speaking about lobotomy once, but I had had no idea what they’d meant.

Philip told me that after the surgery, my father was given medication to help with his recovery—but too much medication made him dizzy. When he forgot to take his pills, he would have seizures.