Heart Earth (5 page)

Authors: Ivan Doig

***

Out of those particles, those waves, this first deliberate dream.

The heavy rain on Christmas Eve of 1944 is contradicting my mother's notion of what both Christmas and Phoenix ought to be. She is trying to work the mood to death, baking an army of cookies and rapidly wrapping Anna and Joe's presents (filmy kerchief for her, carton of cigarettes for him) while they're out visiting friends they know from Montana, and naturally the weather is keeping me inside, which is to say in her hair, until she puts me to crayoning a festive message to my grandmother. I come up with merry Christmas grandma in the countless fonts of my printed handwriting and devote the rest of the page to dive-bombers blowing up everything in sight.

The outside door rattles open, solving the whereabouts of my father, late from the aluminum plant this night of all nights. But his inevitable approximate whistling of "The Squaws Along the Yukon" doesn't follow on in to the front room. All of a sudden he is in the kitchen with my mother and me, checking us over with his sheepcounting look even though we can only tally up to two. Puts his lunchbox down. Goes to the silverware drawer, takes out a tableknife, heads back to the front room where he jams the blade into the crack under the doorway casing so that the knife snugs the door unopenable. (Whatever this is about, Anna and Joe are in for a surprise when they come home and try to get in.) He zips back into the kitchen, pours himself a cup from the constant coffeepot and begins his news ever so casually, as he likes to do.

"Did ye happen to hear?"

I have only one fact in meâthat it's about to be Christmasâand my mother but twoâthat it's about to be Christmas and we are an interplanetary distance from anybody and anywhere we knowâand so my father's bulletin arrives spectacularly fresh. Leave it to him, he has pried it out of one of the aluminum plant gate guards who were giving everybody a going-over at tonight's change of shifts, making the entire workgang shuffle through in single-file so their security badges could be hawkishly inspected.

"A whole hell of a bunch of German prisoners got away," is the report my father brings. The great breakout at the Papago Park prisoner-of-war camp had been engineered by U-boat men, tunnel-visioned in the most effective sense: somehow they dug through a couple of feet of hardpan a day for the past three months, and tonight twenty-five of them have moled out to freedom, under the cover of ruckus set up by their comrades. "They're watching for the buggers everywhere."

Including, now, 119B.

"What's next in the stampede," murmurs my mother, simply in commentary of German POWs added to the rest of the deluge out there. Tonight she wouldn't be surprised if the moon itself came squashing down on Phoenix.

Meanwhile I am scared, flabbergasted, and inspired.

A tunnel!

A foxhole is nothing compared to that; tomorrow will not be too soon for me to start my sandhog future beneath Alzona Park.

Huns at the door of Phoenix don't faze my father, at least with a caseknife jamming that door. He kids my mother about the Gluns and Zettels on her side of the family, "Just remember, Berneta, if the MPs come around here you're not related to those sauerkraut cousins of yours back in Wisconsin."

What?

What?

I'd done my teething on the war, could never remember when the grown-ups were not inveighing against Japs and Krauts. And nowâ

"Mama? Are we

Germans?

"

My mother shoots my father a now-look-what-you've-started look. "We're pedigreed Scotch," he assures me, but can't resist adding: "Even you and Mamaâye both caught it from me."

I am determined to get this matter of breed straight. "How did we catch it?"

My father gives the handsome jaunty grin off the Grass Mountain photographs. "It got pretty contagious there for a while."

Naturally I want to follow up on that, but my mother, business to do with cookies and wrapping paper, pokes another look at my father. "Do you figure you're about done stirring him up?"

"I guess maybe so," he acknowledges as he studies her. "Now what can I do about you?" All at once he says, so soberly it breaks on the air as a kind of plea:

"Merry damn Christmas, Berneta."

Realization lifts her upper lip in the middle, her index of surprise. She honestly hasn't known how much her mood has been showing. She is at a loss. "Charlie, I onlyâ"

She hunches her shoulders a little, smallest shrug, but on it ride all the distances of this Christmas. Not only is my mother ten hundred miles separate from her own mother and father, they have separated from each otherâmy grandmother is cooking on a ranch in another part of Montana from Moss Agate and my grandfather is in parts unknown. Bounced like dice against the war's longitudes and latitudes, Wally is somewhere in the Pacific, my army uncle Paul is in Australia, here we are in aluminized Arizonan Alzona. This sunward leap of ours has been my father's doing, for my mother's sake. More and more spooked by her asthma battles in the isolation of the Faulkner Creek ranch, he flung the place away, piloted us out of Montana on war-bald tires and waning ration books, recast himself from ranchman into aluminum worker, he has desperately done what he thought there was to do, made the move to Arizona for the sake of health. For her sake. But he can see the immense journey unraveling here on the snag of Christmas, homesickness, out-of-placeness, and now he is looking the plea to her, everything gathered in his eyes pulling the square lines of his face tight.

Fuss about her health has always put a crowbar in my mother's spine and it does again now. She straightens up as if shedding this hard year. She tells my father all the truth she has at the moment.

"I'll try to get over this, Charlie."

She takes a breath as big as she is, not an asthma gasp but just fuel for what she needs to put across to him about her isolation amid a cityful of strangers, how she misses everything about Montana there is to miss.

"It's going to take some trying," she lets him know.

Invisible in plain sight at the kitchen table, crayoned combat forgotten on the tablet paper in front of me, I watch back and forth at these gods of my world in their confusion.

At last my father nods to my mother and says as though something has been settled: "That's all we can any of us do, Berneta, is try."

***

The escaped Germans do not devour us in our Christmas Eve bedsâhightailing it to nonbelligerent Mexico seems more what they had in mindâand so we climb out to the day itself and its presents. Up out of the fiber of that boy who became me, can't my Christmas gift prospects be readily dreamed? Tricycle? Toy truck? Wicked new shovel? No, beyond any of those. Threadbare Alzona Park presented an actual item more magical than imagined ones can ever be. From out beyond the world's possibilities, I have been givenâ

The

Ault.

Blessed conspiracy of Wally and my mother, this; he by mailing it in time and she by sneaking the gift wrapping onto this toy replica of his ship. Replica does not say it, really, because my

Ault

was tubby, basicâa flat-iron-sized vessel with a block of superstructure and a single droll dowel of cannon poking out, more like a Civil War ironclad than anything actually asteam in the United States Navy in 1944; but painted a perfect navy gravy gray, and there on the bow in thrilling authentication, the black lettering USS

Ault.

Wally would have had to go to the dictionary for

avuncular,

but he managed to give me a most benevolently unclelike warship.

Naturally the grown-ups have wasted Christmas on each other by giving dry old functional things back and forth, so while Anna and Joe and Dad and even my mother try to have what they think is a good time, my

Ault

and I voyage 119B all that day, past Gibraltars of chair legs, through the straits of doorways to the bays of beds. (All December the logbook of the actual

Ault

has been repeating an endless intonationâ0440

COMMENCED ZIGZAGGING

. 0635

CEASED ZIGZAGGING

. 0645

RESUMED ZIGZAGGING

âas the newly commissioned destroyer practiced the crazystitch that would advance day by day from Pearl Harbor to Tokyo Bay.) We make frequent weather reconnaissances to a window, for my mother has promised that if the rain ever stops we can breast the moistures of Arizona outside.

All the while, all this holiday, although I am not to know so until the letters return forty-two years later, my parents and I and Arizona are on Wally's mind. Along with my gift ship arrived his inquiry to my mother whether she thinks he would have any prospects where we are, after the war; are there flour mills and feed stores where he might land a trucking job?

Through us, like a signal tremor along a web strand, Phoenix is making itself felt even into the most distant Pacific. You can feel the growth thrust gathering (it undoubtedly is what my mother has been feeling), the postwar land rush coming when you can throw a doorknob on this desert and a dozen houses will sprout.

Yet my mother, glad as she would have been to have him on hand in our future, does not sing back what her favorite brother wants to hear.

As she was with my father, she will be doggedly honest with Wally, sending back to him that she really can't be sure how his chances would be here where I am dreamily

Ault

ing and where my father has brought our hopes.

There is plenty of Phoenix I haven't seen,

she will write with pointblank neutrality.

***

Our story, my mother's, my father's, mine, would seem to need no help from imagination to predict us onward from that 1944 Christmas. Americans of our time lived some version of it by the hundreds of thousands, ultimate millions, as Phoenix's population greatened beyond those of Boston, Baltimore, Pittsburgh, Cleveland, Milwaukee, beyond that of entire states such as Montana, as America's center of gravity avalanched south to the Sunbelt. The picture of us-to-be is virtually automatic. My father doctors his way out of the ulcer siege, my mother's asthma stays subdued and her homesickness begins to ebb, we continue on as self-draftees in the sunward march of America. Sheepkeepers no more, now we be bombermakers. Naturalized Alzonans, no more or less ill-fitted for project living and eventual suburbs than any other defense work importées. As this last war winter drew down toward all that was going to burgeon beyond, we were right there at hand, ready-made, to install ourselves into the metropolis future that was Phoenix. Except we didn't.

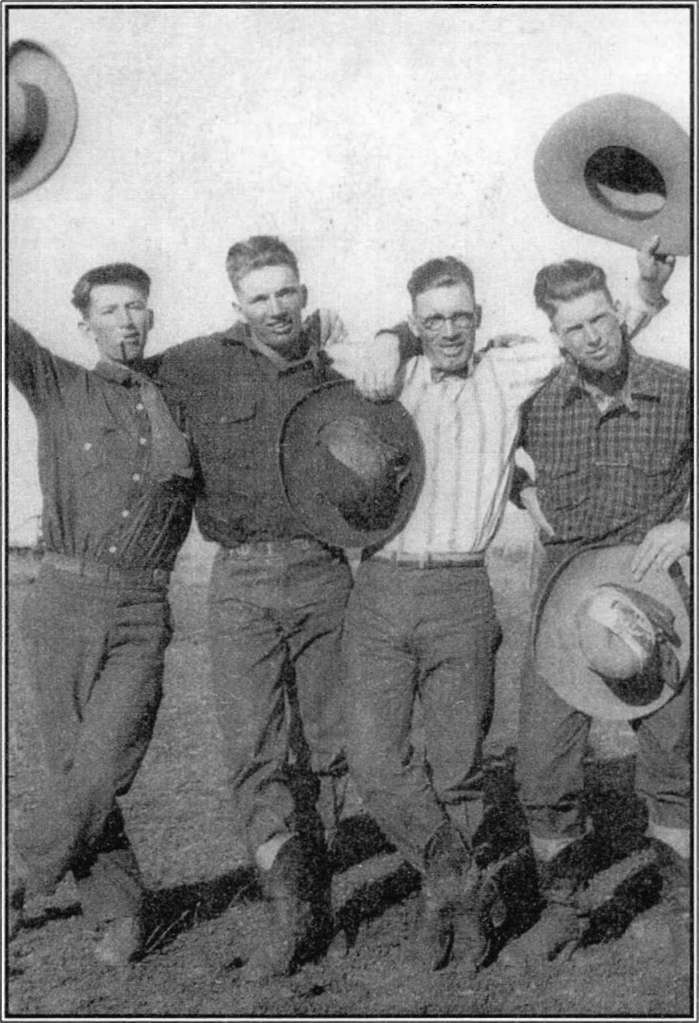

The Doig boys in the 1920s; Charlie, in the striped shirt, with three of his cowboy brothers.

We two, my mother and I,

navigate among the cacti. The road from the cabin threads in and out of any number of identical pale braids of wheel tracks, but we have memorized strategic saguaros, arms uplifted like green traffic policemen, at the turns we need to make. Behind the steering wheel of the Ford my mother keeps watch on the cloud-puffy March sky as much as she does our cactus landmarks. She hates bad roads (and has spent what seems like her whole life on them) but at least these of the desert are more sand than mud.