Heart Earth (8 page)

Authors: Ivan Doig

Quite a gabfest,

my mother puts down in her desert chronicle to Wally and ultimately to me, and I am surprised when I find she doesn't even remotely mean hers and my father's.

The old miner did all the talking, just about.

But yes, the miner. Guerrilla cattle aside, our only caller at the cabin.

Before realizing dudes and tourists were the real lode, Wickenburg originated as a goldstrike town, and prospectors still were tramping around in the hills trying to hit the yellow rainbow again. I dream our miner upward from his visit to my mother's recording pen on the twenty-second day of March, 1945. Story-become-person, he comes refusing to look like a desert oreseeker is expected to, other than a few missing finger joints. Instead of shag and beard he sports a precise white mustache like a sharp little awning over his mouth, and a snowy pompadour he keeps in place by lifting his hat straight up when he takes it off in highly reluctant acknowledgment of my mother, womankind. Or maybe he is simply uncorking everything stored up since he last kept company with anyone besides himself in his shaving mirror.

In windjammer style he fast sets us straight about the war (England is who we ought to be fighting) and about the president (Franklin The-Hell-No Roosevelt, in the miner's indignant rendition of the person who took the nation off the gold standard).

Wide-eyed I wait for the battle to erupt over President Roosevelt, great voice that strode out of the radio with every word wearing epaulettes, president for perpetuity if the votes of my parents have anything to do with it.

But skirmish is all anybody wants to risk here, my mother saying only that at least people don't need to eat gophers anymore as they did during Hoover's Depression and my father saying at least Roosevelt is aware of the existence of the working man and the miner saying that when you come right down to it England and Roosevelt are only pretty much the same blamed thing, you can hear it in how they both talk.

Politics disposed of, the miner plunges on to his experiences in the desert generally and here in the Wickenburg country in particular, which is what my folks want to hear from him, local knowledge. Arizoniana, not to mention Wickenburg weather wisdom, they could stand to have by the bale. Used to dealing with loopy sheep-herders, my father and mother cross their arms and let the soliloquist unravel while I restlessly wish he'd get going on how to tell gold from rock.

Then one particular squirm of mine seems to remind our filibustering guest of something. Montana he is unacquainted with, he announces, but he has been to Dakota, practically the same.

"I was about the size of your fellow here," he indicates me, then squints as if making a vital adjustment. "Little bigger. Anyways, both my own folks had passed away with mountain fever and so my uncle tucked me into his family. This was when he was running a freight outfit into Deadwood, Dakota, the kind of mule train they called 'eight eights.' Eight teams of eight mules each, three wagonsâno, I'm lying againâ

two

wagons to each mule team. This one day my uncle hustled home and got us all, my aunt and his own kids and me, and said we better come downtown and see this. So we went down and here was a big freight jam, right in that one long street of Deadwood. What's happened was, all these freight outfits had lit in from Fort Pierre and Bismarck on one side of the gulch and from Cheyenne and those places on the other, and now couldn't none of them get out either way, frontwards or back. There was teams there of just all descriptions, eight-yoke ox teams pulling three wagons, little outfits with two horses or four horses, mostly mule teams like my uncle's on the Cheyenne end of the traffic. Everything jammed up so tight for about a mile, you could have run a dog on the backs of those freight teams from one end of Deadwood to the other. Everybody's standing around saying 'This is no good,' and finally the big freighters got together and talked it over. One man in the bunch made a motion to appoint my uncle the captain of straightening this thing out. My uncle said, 'Well, boys, if you want me to, I'll take charge.' They said, 'We want you to take charge. Whatever you say is law and we'll back you.' My uncle said, 'Let's get a little more backing than that,' and he went over to his lead wagon and come back with two six-shooters in his belt. So him and the rest of the bunch started through town looking over the mess and my uncle said, 'We might as well start right here,' and he started them in on moving the little outfits to the sidestreets by hand. The little rigs of two horses, four horses, they put them up alleys and onto porches and just anywhere they could find, and that way they'd get some room to bend out a big ox or mule team. It took my uncle and them all night and into the next morning, sorting all those outfits out. He did something in getting that jam cleared, my uncle did."

Magical uncles. Out there ropewalking the dream latitudes, Deadwood, Okinawa, sorting oxen and mules by hand, preserving the

Ault

from submarines below and dive-bombers above. Uncle Sam even, in the cartoons kicking the behinds of Hitler and Tojo. Whatever marvel needed doing, uncles were the key Wait a minute, though. Wasn't this mustache-talker awful old to be in on knowledge about uncles? It was a new thought, that uncles were available to just anybody.

Abruptly the miner declares he has to skedaddle back to his claim, as if needing to collect the nuggets it's laid that afternoon. Dad and I walk with him to the road while my bemused mother makes a start on supper.

Still talking a streak, out of nowhere the miner breaks in on himself and asks what brings us to Arizona.

Dad could answer this in his sleep. "My wife's healthâ"

"Figured so. Could hear it in her."The miner knocks on his own chest. "Got a chuteful of rocks, don't she, there in her lungs. She's young to have it like that."

My father looks as though he has been hit from a blind side. To him, my mother's breathing is not nearly the alarming wheezes of her Montana seizures, or for that matter of our first harrowing night in Arizona four months ago. North of here in the auto court at the town of Williams, high up on the Coconino Plateau, she had put in a horrendous night of gasping spasms. My father would swear on a stack of Bibles that she had improved every foot of the way down from nightmarish Williams to this desert floor. True, one other severe spell hit her during our Phoenix try, but not nearly as bad as that Williams siege, as any of a dozen heart-hammering emergency runs from the Faulkner Creek ranch. Surely to God this desert air is making Berneta better, isn't it? Yet how much better, if an utter stranger can pick out the trouble in her lungs as casually as the tumult in a seashell.

My father stares at the miner. Finally he can say only: "She's ... thirty-one."

Charlie range-branding a calf.

I can hear that day of mice and thread.

The needle of Winona's portable sewing machine sings over the material to the treadlebeat of her foot, our kitchen table is gowned with the chiffon she is coaxing to behave into hem. This way and that and the other, she jigsaws the pattern pieces she and my mother have scissored out. My mother is no bigger than a minute in build and Winona minuter yet, so they are resorting to a lot in these prom dresses. The latest nomination has been ruffles.

"I think ruffles would go okay, Nonie, don't you? Give us a little something to sashay?"

"What the hey, we'll ruffle a bunch up and see," pronounces Winona. Her voice is bigger than she is, deep, next thing to gruff. "If I can find my cussed ruffler."The sewing machine treadle halts while Winona conducts a clinking search through her attachments box. "Did you have the radio on, Berneta, the other day? I didn't know a thing about it until the kiddos told me the next morning. I about dropped my teeth."

"I wish to Halifax I hadn't heard, but I did. I had it on while I was in here trying to scrub down that oldâ"

Where I am holed up behind the couch in the living room, as usual overhearing for all I am worth, comes the somersault snap of another mousetrap going off.

"My turn at the little devils?" Winona volunteers.

"I'll fling this one," says my mother, "you're doing so good on the dresses."

"I thought Ringling has mice something fierce," Winona gives out with. "But cripes, this place!"

"We tried a cat, did I tell you?" An old marmalade stray one, half its tail gone, whom my mother nonetheless cooed

kitten-katten

to. "He only lasted two days. Charlie swears the mice ran the cat out of town."

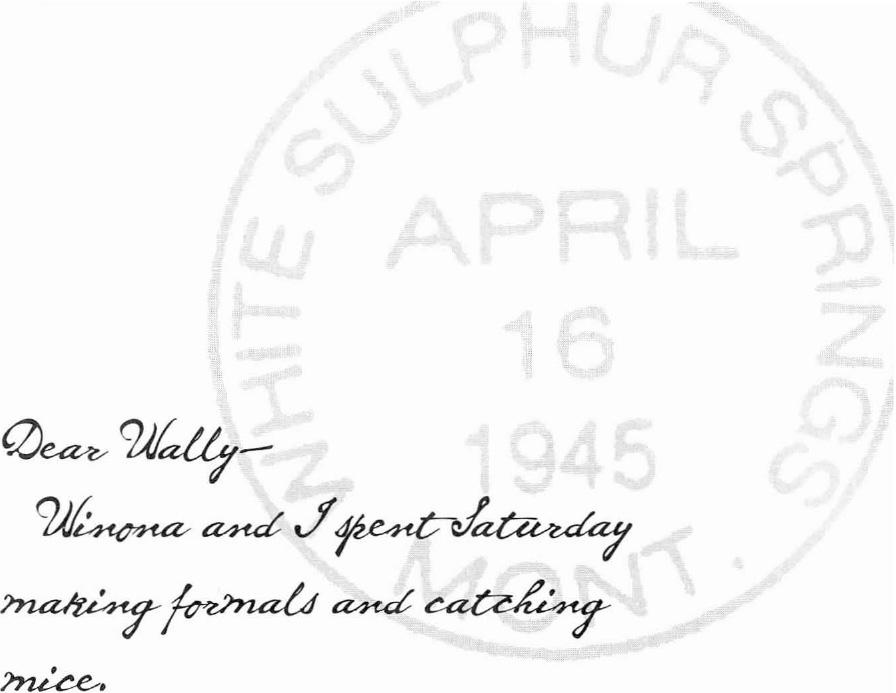

Both women laugh, until I hear my mother putting on overshoes to take the expired mouse out to the garbage barrel, feel the wind make its presence all through the house when she opens the back door. Blowy April, a thousand and fifty miles north of our Arizona try. We have reverted to Montana, pulling out of Wickenburg at the end of March (

Kind of anxious to get home, see everybody, find out how I'm going to feel, figure out what we are going to do this summer,

my mother's last words to Wally from the desert cabin) to climb back up the continent through Flagstaff and Kanab and Provo and Salt Lake City and Pocatello and Dillon and Twin Bridgesâand after all that, we still are nowhere much. This rented house on a side street in White Sulphur Springs is as dreary as it is drafty, its only companionable feature the mob of mice.

Busy busy busy, Winona's Singer goes again. I laze in my own territory, the triangle cave of couchback and room corner it angles across. My books, my trucks, my tubby

Ault,

are cached in here with me out of the prevailing weather. The wind steadily tries to pry out the nearest windowpane.

Seems as though it blows & storms all the time,

my mother has reported this polar Montana spring to Wally,

we're having our March weather in April.

We are having gabstorms and earquakes, if I know anything about it. Since Thursday I've nearly listened myself inside out. This is a job with work to it, this spying on history. Who can tell what will distill next out of the actual air, after Thursday afternoon when my mother had her programs on,

Ma Perkins

or some such, I wasn't much listening until the news voice cut in: "We interrupt this program to bring you a special bulletin..."

When the bulletin was over, I came out from behind the couch on all fours, then stood up curious into another age.

In the kitchen, stock-still, scrubbing brush still in her hand where she had been slaving away at the rust stains on the ancient sink drainboard, my mother stood staring at the radio as though trying to see the words just said.

"Mama? When Daddy gets home, are we going to wash the car in the creek?"

"I ... I don't think so, dear. President Roosevelt's funeral isn't going to be here."

Everything rattles on in the kitchen now, full days later; the dressmaking, the chitchat, their medical opinions on my father who, sore side or not, goes winging out of the house every day to put in twelve hours in a lambing shed

(he really shouldn't be working but then you know Charlie),

rosters of who's home on leave from the war and apt to be met up with at the prom (the White Sulphur Springs high school spring formal amounts to a community dance, as any dance in that lonely Big Belt-edged country tends to), denunciations of this wintry spring, you name it and the smart cookies in the kitchen will do you a two-woman chorus of it. This peppy visit from Winona amounts to a special bulletin itself. Cute yet industrious, Winona looks like a half-pint version of Rosie the Riveter except that, slang and gravelly in-this-for-the-duration voice and all, she is a schoolteacher. Winona I suppose I am a bit shy of, her firecracker energy, her sassy eyes. Kiddo, she calls me. But really,

kiddo

is a hundred times better than the excruciating

Pinky

which some of White Sulphur's downtown denizens call me because of my red mop of hair, and in the right tone of voice I think it also makes an improvement over

Ivan.

Now Winona is off on hats. She's seen a zippy spring number in the Monkey Ward catalogue she is sure she could make for my mother. Living out of suitcases as we have been for the past half year my mother's wardrobe can stand any first aid it can get, so the women talk headgear until the next mousetrap springs. This time Winona, insisting she wouldn't want to get out of practice, takes a turn at disposing of the deceased mouse. Quick as she scoots back in from the garbage barrel, the conversation again becomes fabric and color and whether to veil or not, yet how much more than hat chat is going on.