Heart of Europe: A History of the Roman Empire (103 page)

Read Heart of Europe: A History of the Roman Empire Online

Authors: Peter H. Wilson

Rudolf I’s election as king in 1273 transformed the situation by adding royal power to the Habsburgs’ already considerable regional influence thanks to his family’s existing possession of the county

jurisdiction around Zürich. Rudolf’s policy of Revindication (see

pp. 382–6

) appeared particularly threatening to many Swiss lords and communities who perceived it as a bid to consolidate Habsburg power along the Upper Rhine and western Alps. The famous ‘oath comradeship’ (

Eidgenossenschaft

) between the three incorporated valleys of Uri, Schwyz and Unterwalden was made in August 1291, two weeks after Rudolf’s death, because they feared the election of another Habsburg as king.

69

Such associations were not uncommon, and that of 1291 was not celebrated as the foundation of Swiss independence until 1891. It was directed against a perceived lordly threat, and was not a bid to leave the Empire. Indeed, Alpine communities generally looked to the emperor to consolidate their autonomy by enshrining it in legal charters. Henry VII granted a privilege in 1309 endorsing the three valleys as self-governing rural feudatories forming their own imperial bailiwick directly under him.

Imperial politics again intervened to push this development, since the double election of 1314 raised the possibility of another Habsburg, Frederick ‘the Fair’, as king. Frederick’s relation, Duke Leopold of Austria, intervened to punish the Schwyz peasants who had plundered Einsiedeln abbey, which was under his protection. His punitive expedition was defeated at Morgarten on 15 November 1315, though only around 100 of his troops were killed, and not the thousands claimed by some later historians. Nonetheless, it was a significant reverse, precipitating the collapse of Habsburg influence in the area based on possession of the rights of imperial bailiff. The three valleys renewed their confederation, which was increasingly known to outsiders as the

Schwyzer

, or Swiss. Their status of imperial immediacy elevated the confederates above other rural communities and made them acceptable partners for cities like Bern and Zürich, enabling the Confederation to expand between 1332 and 1353 through additional alliances with other cantons.

Habsburg regional influence, however, grew simultaneously with the acquisition of the Breisgau (1368) immediately to the north and the Tirol (1363) to the east, while their competition with the Luxembourgs encouraged redoubled efforts to reassert authority over the Swiss. Habsburg defeats at Sempach (1386) and Nüfels (1388) coincided with the First Civic War (see

pp. 574–5

above) and the general backdrop of protest following the Black Death. The Alpine communities further

east responded to Habsburg encroachment from the Tirol by forming the God’s House League (Chadé, 1367), Rhetia, or the ‘Grey League’ (Grisons, 1395) and the Ten Parish League (1436). They combined in 1471 as a federation known as the ‘Three Leagues’ (

Drei Bünde

), which encompassed 52 communities with a total population of 76,000 by the eighteenth century.

70

A further ‘League above the Lake’ emerged among communities south of Lake Constance during a revolt by the Appenzell region against the abbot of St Gallen in 1405. Although joined by communities in the Vorarlberg, Upper (southern) Swabia and the imperial city of St Gallen, this league was crushed by the local knights combining as the League of St George’s Shield in 1408.

Despite the sharper social tension, localism and conflicting interests prevented a broad alliance between the different Alpine leagues. The Swiss allied with Appenzell in 1411, but only admitted it as a member of their Confederation in 1513. Each of the Three Leagues allied separately with the Confederation in 1497–9, but reaffirmed their own federation in 1524. Meanwhile, the Swiss pursued their own policy of expansion, conquering the rural communities of the Aargau (1415) and Thurgau (1460) from the Habsburgs. The growing military reputation of the Swiss allowed their leaders to sign lucrative contracts with the French king and Italian princes to supply mercenaries, entangling the Confederation in more distant politics, notably the wars against ducal Burgundy from the 1440s to 1477, and the Italian Wars after 1494.

71

The Swiss also responded to Burgundian and Savoyard pressure from the west and south by accepting the imperial cities of Fribourg (1478) and Solothurn (1481) as members. The Valtelline and other parts of Milan were conquered by the Swiss in 1512.

These conflicts were frequently brutal: Swiss and German troops waged ‘bad war’, meaning the normal rules governing the taking of prisoners were suspended. However, the wider context remained strategic rather than ideological. France’s intrusion into Italy after 1494 heightened the significance of the Alpine passes to the Empire’s integrity. Crucially, this coincided with the peak of imperial reform, forcing the Alpine communities to define their relationship to the Empire. Their earlier conflicts with the Habsburgs had left them suspicious of the new Reichstag, and they refused the summons to attend meetings after 1471, in contrast with the German cities who used this opportunity to integrate themselves in the Empire as full imperial

Estates. The Swiss held their own assemblies (

Tagsetzungen

) after 1471. These drew in Basel, Zürich and other local towns like Luzern, which might otherwise have participated in the Reichstag, while the Three Leagues held separate meetings, especially after renewing their federation in 1524.

The introduction of the Common Penny tax in 1495 forced a decision. For the first time, the Empire was asking the Alpine communities for a substantial financial contribution, yet appeared to offer little in return, having largely left the Swiss on their own to repel the Burgundians before 1477. Moreover, the Swiss did not feel the need for the new imperial public peace, because they had already agreed a version of this through their own confederation. The Swiss refusal compelled Maximilian I to respond with force to assert both his imperial and Habsburg regional authority. The resulting conflict was known (depending on perspective) as the Swiss or Swabian War.

72

Maximilian mobilized the Swabian League on the basis of his membership as ruler of Austria and the Tirol in January 1499. The Swiss won three victories, but failed to cross the Rhine northwards into Swabia, and so accepted the compromise Peace of Basel on 22 September.

It would be premature to call the treaty the birth of Swiss independence. The Swiss were granted exemption from the taxes and institutions agreed at the 1495 Reichstag, but otherwise remained within imperial jurisdiction. Both the Confederation and the Three Leagues continued to display their roots in the Empire’s socio-political order. They remained networks of separate alliances between distinct communities that retained their own identity, laws and self-government. In this respect, the Confederation failed to match the Dithmarschen peasants who already had a codified constitution and common legal system by the mid-fifteenth century. Neither the Confederation nor the Three Leagues had a capital. A few communities remained apart, notably Gersau, which effectively acquired imperial immediacy when its local lord sold his rights to the parishioners in 1390. As with the other places, Gersau’s inhabitants secured imperial confirmation of their immediacy (in 1418 and 1433). Although they had cooperated with the Swiss since 1332, the fact that their tiny community was only accessible by boat across Lake Luzern enabled them to remain fully autonomous until 1798, when they were forced by France to join the Swiss Confederation and the Three Leagues in the new Helvetic Republic.

73

The Confederation eventually encompassed 13 cantons with 940,000 inhabitants by 1600.

74

Basel, Bern, Luzern and Zürich were civic republics that had extended economic and political dominance over their rural hinterlands similar to the pattern in northern Italy. Tensions from this process erupted periodically into civil war, notably between 1440 and 1446 when Zürich was temporarily expelled from the Confederation. Confessional differences following the Reformation exacerbated existing rivalries. Renewed conflict prompted a compromise in 1531 that prefigured the Empire’s Peace of Augsburg (1555) by fixing the confessional identity of each canton. The six Protestant cantons were especially concerned not to push their seven Catholic neighbours into a closer alliance with the Habsburgs.

The Swiss rejected the formalized status hierarchy entrenched in the Empire by imperial reform, and instead did not differentiate between the more urbanized and the rural cantons, each of which had two votes in the federal assembly. However, canton boundaries reflected their origins as imperial fiefs, meaning they varied considerably in size and wealth. Protestant wealth and population grew faster, adding to the resentment that the Catholics had two more votes. The Peace of Aargau stabilized the Confederation after renewed civil war in 1712, but without resolving the underlying problems. Meanwhile, both the Confederation and the Three Leagues controlled subordinate dependencies conquered collectively during their period of territorial expansion between 1415 and 1512. These areas retained self-government, but were denied representation in the federal assemblies. The Italian-speaking Catholic inhabitants of the Valtelline especially resented domination by the Protestant German-speakers of Rhetia, leading to prolonged unrest between 1620 and 1639.

75

In short, the exclusion of superior lords did not bring peace, but was followed by serious socio-economic and religious divisions.

Social practice remained hierarchical, and only outsiders believed the Swiss were all ‘peasants’.

76

Swiss equality involved the assertion that they were equal to any noble, opening the door to a noble lifestyle for those who could afford it. Lordly jurisdictions were converted into property rights that generally passed to a class of powerful, rich families like the Salis, Planta, Guler and Schauensteins in Rhetia, for instance. These displayed their status through coats of arms, and used their near monopoly on communal posts like district judges or military commanders

to secure access to the best meadows and take control of lucrative transit trade. Rhetian politics became particularly nasty during the later sixteenth century when unscrupulous leaders exploited mass assemblies of enfranchised citizens to promote their own agendas, which could culminate in armed intimidation, kangaroo courts or, in the worst case, the sectarian massacre of 1620. Populist politics exposed communalism’s dark side and was, unfortunately, the one area where the Alpine communities deviated substantially in political culture from the Empire.

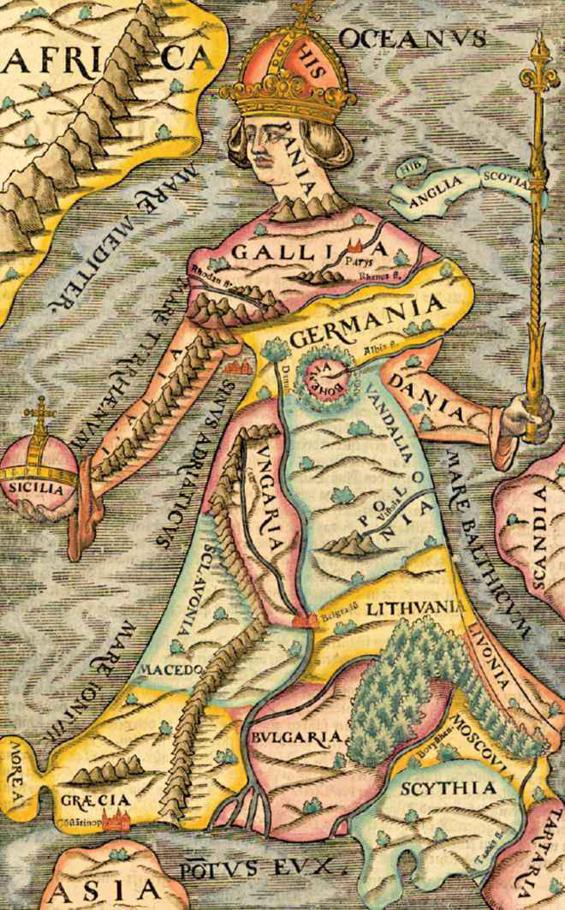

17. Johannes Patsch’s 1537 map of Europe as a single Empire, with Habsburg Spain as its crowned head.

18. The sober woman from Metz, from Hans Weigel’s

Trachtenbuch

of 1577.

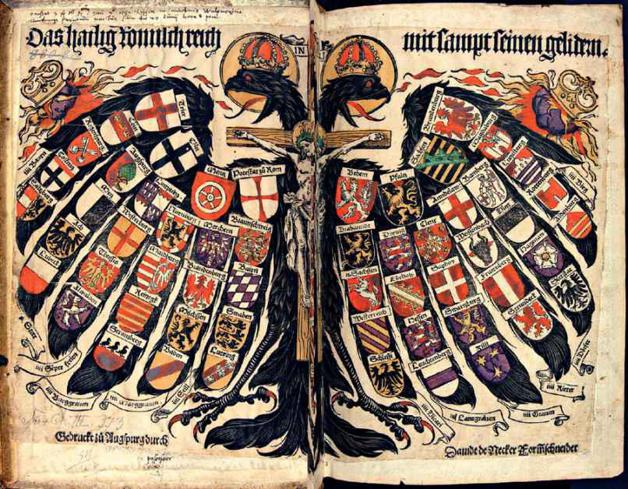

19. Hans Burgkmaier’s 1510 version of the

Quaternionenadler

, showing the Empire’s corporate order in groups of four locations identified by their heraldic device, topped by the seven electors and the papacy.