Heart of Europe: A History of the Roman Empire (51 page)

Read Heart of Europe: A History of the Roman Empire Online

Authors: Peter H. Wilson

His contemporary, Georg Friedrich of Waldeck, asked ‘Where outside the Empire can one find such freedom as is customary within it?’ While leading princes sought crowns elsewhere in Europe, they continued to engage in imperial politics. The elector Palatine commissioned two copies of the imperial crown in 1653 to give substance to his new

title of Arch-Treasurer, awarded as part of the Westphalian settlement.

66

As the emperor’s immediate vassals, the imperial knights also identified closely with the Empire. Although territorial nobles were encouraged to be loyal to their prince as immediate lord, they also looked to the emperor, because only he could grant the coveted status of full immediacy. The close juxtaposition of the different territorial nobilities combined with their relatively small size to encourage individuals to seek careers across the Empire. Often criticized by contemporaries as provincial hicks, most German nobles were at least aware of wider intellectual, educational, scientific, military and political networks. They saw themselves as a distinct ‘nation’ within a broader European aristocracy. Many families had branches in Burgundy, Italy, Bohemia and outside the Empire. Like educated commoners, they saw no contradiction between cosmopolitanism and multiple, more focused loyalties.

67

The Empire’s decentralized structure never employed a large staff. For most of the Middle Ages the ‘imperial personnel’ barely extended beyond the imperial chapel and the emperor’s immediate household. Ruprecht gave the post of councillor to just 107 men across his reign (1400–1410). The establishment of permanent central institutions increased numbers somewhat after the 1490s. At least seven hundred people were employed at the Reichstag in the 1780s, with another 150 at the Reichskammergericht; but even adding the Reichshofrat, the chancellery and other agencies, the total is unlikely to have been more than 1,500.

68

Unlike other large states in early modernity, the Empire lacked permanent armed forces that might otherwise have served to encourage ‘national’ loyalty.

However, to look for such institutions would miss how the decentralized structure created numerous layers of engagement and identification. All imperial Estates sent envoys and agents not just to the Reichstag but to each other. The Empire defined their world. Only a few of the larger principalities maintained representatives at foreign courts by the eighteenth century. These roles had been performed by clergy during the Middle Ages, providing another example of the imperial church’s significance to the Empire. The spread of educational opportunities from the high Middle Ages led to the rise of the ‘learned’ (

Gelehrten

), recruited largely from patrician families, who formed the backbone of most territorial administrations throughout early modernity. Like their noble counterparts, they were often highly mobile,

working in several courts and imperial cities across their careers, which often included stints at the Reichstag or other institutions – like Goethe, who was a legal trainee at the Reichskammergericht before becoming a minister in Sachsen-Weimar. The experience of these men was as much imperial as territorial.

69

Some, like Goethe, were ambivalent about the Empire, while others, like Moser, were enthusiasts. Those serving larger territories could be more critical, but the Hohenzollerns’ Reichstag envoy, Count Görtz, lamented the Empire’s demise and chose to retire in Regensburg rather than return to Prussia.

70

Rather more significantly, identification with the Empire stretched far deeper than the political and administrative elite. Despite their problematic relationship with many emperors, the Empire’s Jews continued to pray for their welfare until 1806. Evidence that attachment extended beyond such official acts is provided by the blessings to the emperor recorded in family memory books (see

Plate 9

). Although Frankfurt Jews were confined to their ghetto on election days, they were included after 1711 in the homage ceremonies to new emperors. Jews performed homage ceremonies in four other imperial cities, though Worms council successfully petitioned to have the one there stopped. The episode perfectly demonstrates how identification with the Empire worked. The Jews saw their participation in such ceremonies as a way to assert their own corporate identity, while Christian city councillors sought to prevent this to achieve the opposite. Individual communities could also see the Empire as a framework for common action, exemplified by the Franconian Jews who in 1617 prosecuted the bishop of Bamberg on behalf of all their co-religionists to prevent him from requiring them to wear a star badge. Far from heralding a new dawn, many Jews perceived the Empire’s demise as a disaster, since it removed the legal protections that had been corporate in line with their own visions of community, unlike the individual freedoms granted by post-1806 states.

71

The imperial cities also found emperors to be problematic patrons and so already during the twelfth century these cities emphasized their relationship to the Empire as transpersonal. Later medieval emperors relied on the cities to accommodate them during their royal progresses, and their entry was always a cause for lavish celebration. Frederick II’s third wife, Isabella Plantagenet, was greeted by 10,000 people when she arrived in Cologne in 1235. Royal entrées became increasingly elaborate around 1500 as the Habsburgs fused Italian and Burgundian

ideas with classical examples supplied by Humanist scholars. Emperors’ arrivals were now marked with elaborate triumphal arches, decorated floats and obelisks. The practice continued into the late eighteenth century, though modified in line with changing styles to include processions of state coaches and military parades. Arrivals for imperial elections, coronations and (until 1663) Reichstag openings were on an especially grand scale: 18,000 people participated in the procession of the electors into Frankfurt for the 1742 imperial election, equivalent to half the city’s population.

72

Imperial cities replaced palaces as the Empire’s political venues during the fifteenth century, not just for events involving the emperor, but also for the numerous gatherings of imperial Estates, either in official gatherings, like the regional (Kreis) assemblies, or for their own alliances and congresses. Accommodating these activities could be burdensome, especially with the additional security costs during periods of tension, but such events also brought valuable business into the city and offered communities opportunities to express their own identity and place in the Empire.

73

Augsburg built an imposing new city hall from 1618 to 1622 prominently displaying the imperial double eagle on the portico in the hope of encouraging the Reichstag to choose it as a venue, as well as a statue of Emperor Augustus to stress its origins as a Roman imperial city.

74

Nuremberg was another city proud of its imperial traditions, which had been cemented in 1424 when Sigismund entrusted it with conserving the insignia. These had been displayed publicly since 1315, becoming an annual event each Easter from 1350. Nuremberg’s conversion to Protestantism ended this tradition in 1524, because of the Lutheran critique of relics, but the city council refused to release the insignia to the still-Catholic Aachen, which repeatedly petitioned to replace Nuremberg as custodian.

75

Attachment to the Empire extended to ordinary, rural inhabitants as well, despite the growth of numerous intervening layers of lordship between them and the emperor. Indeed, the emperor’s relative distance and absence from daily life appears to have heightened the sense of reverence, and his rare appearances were a source of great curiosity and celebration. This extended even in death: Otto I’s corpse took 30 days to travel the relatively short distance (130 kilometres) from Memleben for burial in Magdeburg so that it could be seen by the crowds along the route. The bishop of Speyer refused to bury Henry IV in his

cathedral in 1106, because the king died under papal excommunication. However, peasants stole the earth from atop his grave outside to scatter on their fields, believing it would improve fertility. Sigismund’s corpse was allegedly left seated on a stool for three days when he died at Znaim in 1437 to enable the crowds to file past.

76

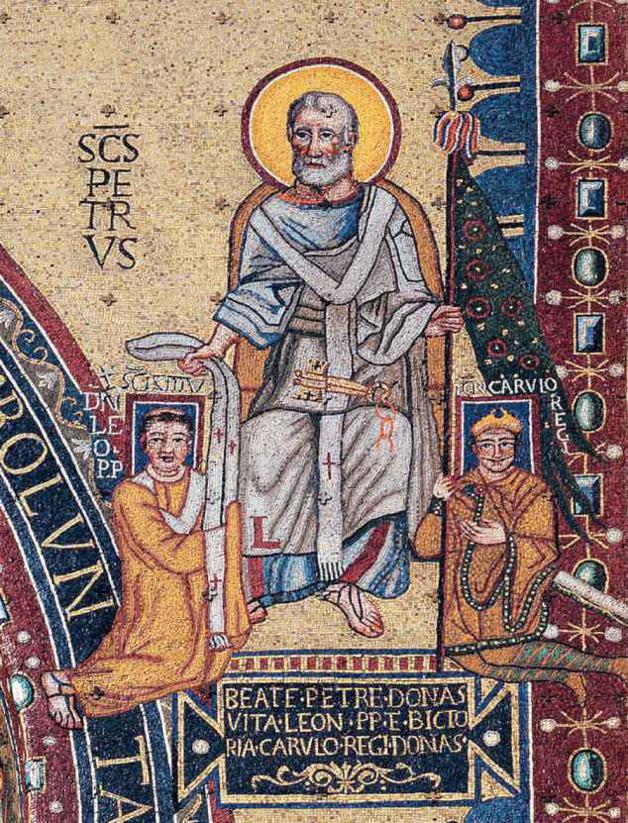

1. The two swords theory: St Peter presenting a pallium to Pope Leo III and a flag to Charlemagne (Lateran palace).

2. Charlemagne as portrayed by Albrecht Dürer in about 1512, wearing the imperial crown and holding the sword and sceptre.

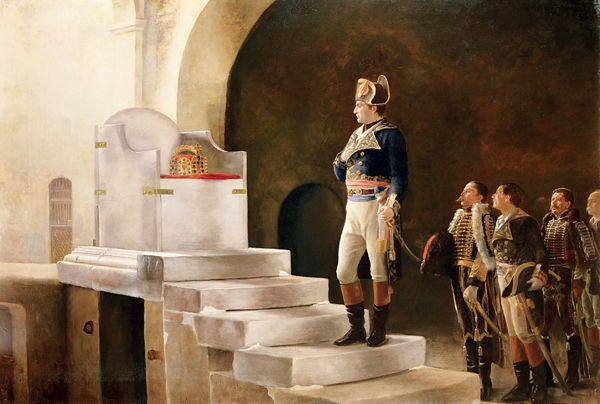

3. Napoleon contemplates Charlemagne’s crown and stone throne in Aachen. The real crown had in fact been removed by the Austrians (late nineteenth-century painting).

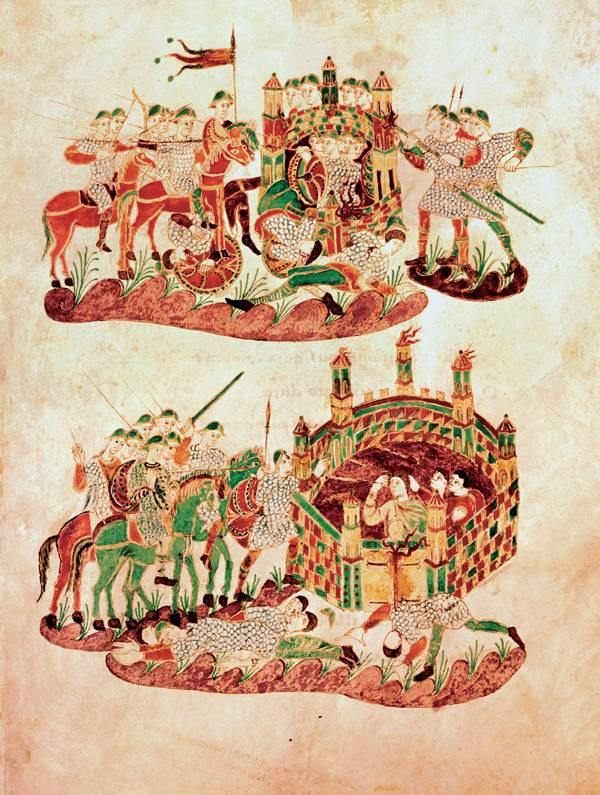

4. Carolingian troops besieging towns (ninth-century manuscript).

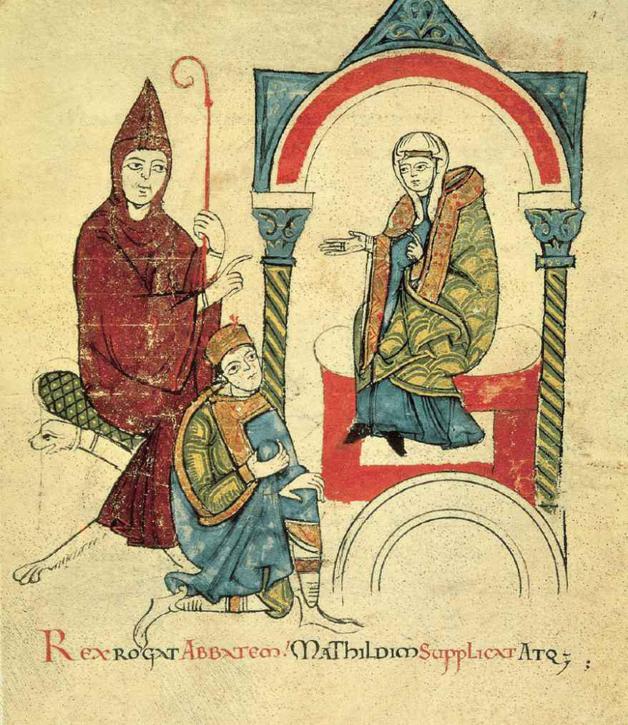

5. The act of Canossa 1077. Henry IV kneels in front of Matilda of Tuscany to seek her mediation, while Abbot Hugh of Cluny looks on from the left.