Heart of Europe: A History of the Roman Empire (52 page)

Read Heart of Europe: A History of the Roman Empire Online

Authors: Peter H. Wilson

6. The

furor teutonicus

. Archbishop Balduin of Trier splits the skull of an Italian opponent during Henry VII’s Roman expedition of 1312.

7. The last papal coronation of an emperor. Charles V and Clement VII in the coronation procession at Bologna in 1530.

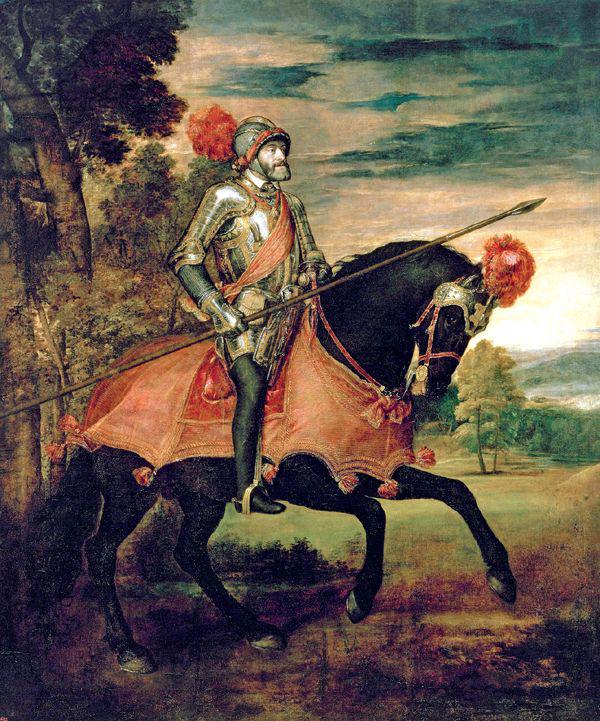

8. Charles V as victor at the battle of Mühlberg, 1547, by Titian. The armour shown in the portrait is preserved in the royal palace in Madrid.

9. Identification with the Empire. A bag made by a Jewish craftsman around 1700 displaying the imperial eagle.

10. Charles V flanked by the Pillars of Hercules and the imperial eagle adorned with the Habsburg Order of the Golden Fleece, c.1532.

11. Charles VI points to Charlemagne’s crown, showing the continued significance of the Empire for the Habsburgs in the eighteenth century.

12. The banquet for Joseph II’s coronation as king of the Romans in Frankfurt, 1764. Note the place settings for the princes who failed to attend in person.

13. The three ecclesiastical electors officiating at Joseph II’s coronation in 1764.

14. Francis II depicted as emperor of Austria in 1832, wearing the Habsburg imperial crown made for Rudolf II in 1602.

15. Figures representing the Slavs, Germans, Gauls and Romans pay homage to Emperor Otto III.

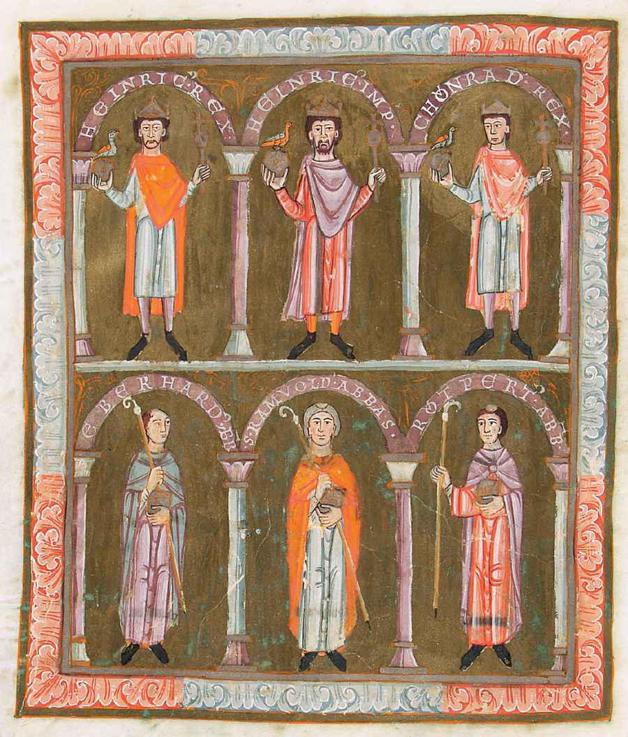

16. The link between locality and Empire. A sequence of three Salian monarchs stands above a corresponding row of abbots of St Emmeram monastery.

The popular enthusiasm to celebrate Francis II’s coronation in 1792 was doubtless heightened by the closure of all the inns and a ban on alcohol sales until his election was completed. However, an analysis of south German sermon texts shows real concern for the welfare of the imperial family.

77

One reason was the widespread identification of the emperor as the peasants’ protector. A collection of popular stories from 1519 recounted how German peasants had aided Frederick I ‘Barbarossa’ in a mythical siege of Jerusalem, while six years later within days of the peasant rebels’ bloody defeat at Frankenhausen at the foot of the Kyffhäuser Mountain there were rumours that Barbarossa would awake to avenge their innocent blood.

78

Changes in judicial practice after the peasants’ defeat opened access to the Empire’s supreme courts, and one quarter of the Reichshofrat’s cases were brought by ordinary inhabitants. So many peasant delegations arrived to petition the emperor that some Viennese inns specialized in accommodating them. Although the Habsburgs tried to restrict direct access in favour of official judicial channels in the eighteenth century, in 1711 three hundred peasants managed to accost the newly elected Charles VI and were delighted at his promise of action. They were still hopeful seven years later, but the likelihood of disappointment was high. One faction in a long-running dispute in Hauenstein in south-west Germany came close to repudiating allegiance to the Habsburgs in 1745. Nonetheless, Hauenstein peasant leaders who had petitioned the emperor gained personal prestige, encouraging several to invent stories of audiences and promises of help. Faith in imperial justice persisted, with unfavourable verdicts blamed on unsympathetic judges rather than on either the emperor or the system.

79