Heirs to Forgotten Kingdoms (41 page)

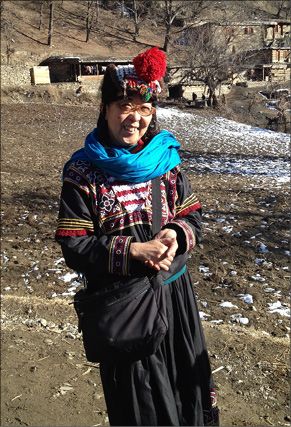

Akiko, a Japanese woman, joined the Kalasha community when she married a Kalasha man twenty years ago. Photo by the author

Azem came up to Zulfikar and me. “I am sorry that you cannot join us,” he said. “Only those who are here in the valley at the start of the festival can take part. But if you had been here,” he said to me, “it would not have been a problem: Muslims cannot join in, but foreigners can.” And in fact I could see a German man, with camera around his neck, and his wife twirling themselves around and waving their arms almost as gracefully as the Kalasha. Presumably he had been there for the goat sacrifice. There was also a lady in full Kalasha costume, complete with cowrie shells—but, unlike any others among the Kalasha women, she was also wearing spectacles. And her features were certainly not Kalasha. She was Japanese. Later I had a chance to speak to her briefly. Her name was Akiko and she had been living in the valley, she said, for twenty-five years. She had come to photograph the region and had fallen in love with a local man. She felt part of a family there, she said: when she visited Japan now, it felt like an alien, individualistic place.

Zulfikar, a Muslim, took his exclusion with good grace, and even apologized to Azem for having shaken his hand (which must have made him impure). “It’s useful for them to have this rule,” he commented to me. “It stops them from being overrun by visitors.” This was not a potential problem in the winter, but I was told that the summer festival attracted many Pakistani tourists who were as intrigued as those from Greece or countries even further afield. Many of the visitors were friendly, but some came with the wrong idea: they expected that because Kalasha women did not wear veils and were not Muslims, they would be available for sex. Lurid tales of a custom called the

budhaluk

—when a Kalasha man once a year was chosen from the community, consecrated himself by spending time in the high mountains, and then impregnated as many women as possible—had helped spread this idea. In fact, the Kalasha are very reserved about sex, and during Chaumos it is completely forbidden even between married couples. This does not stop prostitutes from coming from other parts of Pakistan to exploit the legend by dressing as Kalasha women, though, trading on this desire for the exotic.

In any case, though Zulfikar and I did not actually take part in the afternoon’s dance, we had a good view. It began with a great milling about of Kalasha women—for whom synthetic fabrics have opened up an entire rainbow of colors to wear, oranges and pinks and yellows alongside the traditional red and black—and men, who dressed much more tamely in

shalwar kameez

and Chitrali cap. Kalasha boys had adopted Western clothes and baseball caps. In the midst of the crowd I could catch sight of some brave individuals dancing while surrounded by a circle of chanting and cheering onlookers. Gradually, men and women formed human chains and began to dance in earnest.

Zarmas Gul prepares a traditional meat chapati for the festival of Chaumos, the winter solstice, when days begin to grow longer and nights to shorten. Photo by the author

Men and women danced not as partners but in separate groups, and they chanted as they danced. I asked Azem Beg what the words meant. “It is about the return of the god, coming to rejoin us,” he replied. “And they say our uncles’ sons and our aunts’ daughters have come to celebrate with us.” Every twenty minutes, he said, the chant changed. Over the course of the festivities, the various chants made up a lengthy paean to Balimain, the god of the festival, who comes from afar on a winged horse to collect the petitions of the Kalasha. Children dashed about among the dancing adults, playing games of chase. They were almost never told off. Sometimes the boys would form little groups, linking arms and chanting at the girls. This proved to be a strategic error. One girl realized that the boys, having linked arms, would find it hard to disentangle themselves in time to chase after her. So she kicked the middle boy between the legs and sped away, laughing merrily.

After a while the daytime dancing started to subside, and the Kalasha headed home to prepare for another dance that would take place at night. I went to the guesthouse where we were spending the night, which was run by Azem’s relative Zarmas Gul and her husband. (Again, Gul is not a surname but a term of endearment—it means “flower”—stuck onto the end of her given name.) I watched as Zarmas Gul sat by a wood stove making mutton bread, which resembled a Cornish pasty, but was far better because it was made with fresh meat. An old computer was playing Hindi music alternating with American pop, and while waiting for the stove to heat up, our Kalasha hostess, in her elaborate embroidered dress, moved gently in time with the rhythm of Rihanna. Her daughter sat nearby, wearing a track suit instead of the traditional embroidered dress (“She’s a tomboy, but she does agree to wear Kalasha dress for school,” Azem Beg told me later), and occasionally taking over the computer to play a game on it.

Despite these intrusions of a more modern way of life—made possible, of course, by the power lines that I had seen running along the gorge—the Kalasha daily routine otherwise remains unassisted by modern conveniences. Even the smallest meal in the village took preparation—wood had to be cut, collected, stored, and kept dry, and even to fry an egg, the fire had to be lit. How hard it must be to wash clothes in this freezing winter, I thought. The consolation was that the stove quickly made the room very warm and felt all the more so because we knew how cold it was outside.

Conditions must have been unimaginably tougher for the Kam in Robertson’s time—in an even higher place in the mountains, and without electricity or income from tourism. Yet Robertson said that they were “never melancholy”—perhaps because they were so unremittingly social. They never understood, for instance, that he sometimes wanted to be alone. When he retreated to his room in the hope of writing in peace, he noted in frustration, they assumed that there was something wrong with him and would make a special point of coming into his room and trying to cheer him up. (He could get rid of them only by asking them to teach him their language: teaching him bored them so much that they would invariably walk out almost at once.) The Kalasha, too, seemed content in their valley. Few of them, even among those who had converted to Islam, chose to leave for a career in the cities. From my own Western standpoint, every day seemed to be a struggle for them, but I reflected that they also never had to deal with the problems modern urbanites face: being in a crowd of strangers, being the odd one out, being lonely.

That evening, the second round of dancing began after dark. From our guesthouse Zulfikar and I could see blazing torches appear farther down the valley, and hear the distant sound of singing. Then a group of young men and women materialized slowly out of the darkness and headed toward a nearby field. We followed them, keeping a respectful distance. At the field we saw dots of light appearing all over the hillside, which turned out to be brushwood torches carried by Kalasha descending from their mountain villages. A hubbub arose as people greeted each other, sometimes after months of separation. The dancing lasted through the night, lit by the flames of a huge fire. Even though snow fell steadily, the Kalasha seemed not to notice. Warmth and light and human vigor were driving away the dark and cold, presaging the summer to come. When I got up the next morning, Azem Beg was still awake—he had gone in the early morning, after the dancing, to congratulate a number of couples that had gotten married the day before.

Azem’s father had been an elder among the Kalasha, but they were traditionally an egalitarian and democratic people without permanent leaders. Robertson found that when Kam leaders had to make important decisions, they always waited for other members of the tribe to express an opinion and then agreed with whatever the majority said. In cases where there was a serious division and no clear majority, Kam politicians had recourse to a tactic only rarely employed by politicians in Western democracies: they would literally hide so that they could avoid making a divisive decision. Among the Kalasha, there are elders called

gaderakan

who check to make sure that the community performs its rituals correctly; they are unpaid volunteers, not really priests in the normal sense.

—————

THAT NIGHT I SLEPT IN A KALASHA HOME

, glowing embers in the stove keeping the room warm. In the morning, after the rising sun had taken the edge off the valley’s nighttime chill, I had the chance to see a different style of dancing. Another of the Kalasha valleys—the farthest from Rumbur, called Birir, being several hours’ journey by car—had solstice celebrations of a slightly different kind. Zarmas Gul was from the valley and had told us about the festival, though my own Kalasha companions did not even seem to know about it—it seemed that news did not travel much between Birir and Rumbur, perhaps because few Kalasha either have cars or see strong reasons to leave their own valleys to make the tough journey by foot to see the other Kalasha communities. Azem and Wazir, a Kalasha who had converted to Islam, came with me.

Birir gets few tourists and is poorer than Rumbur, and many of the Kalasha in Birir were living in a large wooden building on the hillside. It was in the old style—built on several levels with staircases linking communal balconies, off which each family had a room. The steep slope of the hillside meant that each balcony was set just a little way back from the one below it. It was far more picturesque than the newer buildings in Rumbur (let alone those in the middle valley, Bomboret, which has been extensively modernized) but also much more cramped.

There was also a collection of houses on the valley floor, and we walked through this and beyond, up the valley a distance and then a short way up the hillside, to a vantage point where there stood a temple called a

jestakhan

—sacred to Jestak, goddess of the family. This was where the festival was taking place. A police guard outside the door had to see my passport before he allowed me into the temple—which was a single room, lined with pillars, all made of wood. Although it had been built recently, it had an air of great antiquity. Perhaps this was because of its interior pillars, which looked like an exoticized version of Ionic columns; perhaps it was the cobwebs on those pillars, which obscured the symbols carved into the wood. Most of the room was in shadow, except that through a square opening in the roof two thin rays of sun lit up the temple wall, and a window looked out onto the icy mountainside. A crowd of boys and girls were staring down at us through the opening, sitting on the roof—I guessed that they might be Muslims barred from entering.

A Kalasha singer has been rewarded for his singing at the Chaumos festival with a shiny cape. Here, outside the temple where the festival is being celebrated with dancing, he wears it proudly. Photo by the author

There were maybe eighty or even a hundred Kalasha in the room. Some sat on a bench at the back, but most were standing; the women in their multicolored dresses were lined up in the shadows. Friends greeted each other as they met, and stood chatting for a time. Others stood quietly listening to three men in

shalwar kameez

and Chitrali caps: one wore a sparkling cloak of synthetic fiber colored red and gold. These three were singing a simple chant in a minor key, consisting only of two notes suggesting sadness. In the corner of the

jestakhan

, two men beat different-sized drums to accompany the chant. Around its edges forty or fifty women formed a long line with linked arms and repeated the chant after the singers; they did not keep strictly to time, and the room was filled with discordant, melancholy notes. Standing among the men in the center of the circle, I had an experience quite different from that at Rumbur. The latter had been rough-and-tumble, while this felt solemn and mystical. The drums beat slowly, the women moved counterclockwise around the edges of the room, and the men sang on. Kalasha men came up to the singers from time to time and put crumpled rupee bills in their caps, a traditional way of rewarding good singing.