Henry V as Warlord (14 page)

Read Henry V as Warlord Online

Authors: Desmond Seward

On 24 October a terrified scout reported to the Duke of York that he had sighted the enemy through the drizzle. The English had just forded the ‘river of swords’, the little River Ternoise. The chaplain tells us that ‘as we reached the crest of the hill on the other side, we saw emerging from further up the valley, about half a mile away from us, hateful swarms of Frenchmen’. They were marching in three great ‘battles’ or columns, ‘like a countless swarm of locusts’,

3

towards the English to intercept them. For the French commanders had decided to make Henry stand and fight, and there was no hope of escape. He had been out-generalled. The English trudged on through the mud and the wet to the hamlet of Maisoncelles, where they bivouacked, preparing to spend yet another night under torrential rain. Even the king was shaken, releasing his prisoners and sending some of them into the French camp with a message that, in return for a safe passage to. Calais, he was ready to surrender Harfleur and pay for any damage he had done. The offer was rejected. A Somerset knight, Sir Walter Hungerford, told Henry that they could do with 10,000 more archers, at which the king rounded on him, retorting that he was a fool since the troops they had ‘are God’s people’. He added, again with a hint of uneasiness, that no misfortune could befall a man with faith in God so sublime as his own.

A set-piece confrontation was the last thing he wanted. He had only seen one before, at Shrewsbury, where he had very nearly been on the defeated side and had almost lost his life. He shared Vegetius’s opinion: ‘a battle is commonly decided in two or three hours, after which no further hopes are left for the worsted army … a conjuncture full of uncertainty and fatal to kingdoms.’ In any case he was more of a gunner, a sapper or a staff officer, than an infantry commander, and this was going to be an infantry battle. It was clearly with the utmost misgivings that he prepared for a general engagement.

According to English sources the French passed the night dicing for the English lords they expected to capture and for the rich ransoms they would demand. Later it was said that they were so confident that they had brought a painted cart with them in which to bring Henry back to Paris as a prisoner. They had plenty of wine and provisions and the sound of their feasting could be heard in the English camp. The Picard squire, Monstrelet, (born in 1390 and a contemporary) tells us, however, that the French passed a depressing night during which not even their horses neighed. He also says that, ‘The English played their trumpets and other musical instruments, so that the whole neighbourhood resounded with their music while they made their peace with God.’

4

For, as all sources agree, the English were understandably terrified, confessing their sins to each other if the queues for priests were too long. The king ordered them to keep silent during the night, under pain of forfeiture of horse and armour for a gentleman, and of the right ear for a yeoman and anyone of inferior rank. (The reality behind Shakespeare’s ‘touch of Harry in the night’.) Armourers were kept very busy servicing weapons, as were the fletchers and bowyers. All were exhausted after their gruelling eighteen-day trek, all were sodden and starving, and all must have dreaded the next morning. Henry had got his trial by battle with a vengeance.

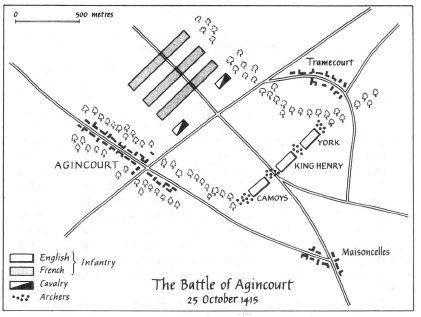

The chaplain, a fearful eyewitness, records how ‘in the early dawn the French arrayed themselves in battle-lines, columns and platoons and took up position in that field called the field of Agincourt, across which lay our road towards Calais, and the number of them was really terrifying’. It was a vast open field sown with young corn, two miles long and a mile wide but narrowing in the middle to about a thousand yards, where a small wood hid the village of Agincourt to the west and another small wood hid that of Tramecourt to the east. The King had spent the night in the village of Maisoncelles to the south, the French in and around that of Ruisseauville to the north. The site, off the road from Hesdin to Arras, remains miraculously unchanged, preserved by the re-planting of trees in the same clumps for generation after generation. On that particular day, because the corn was newly sown and because the rain had been falling for several days, the field had turned into a sea of mud which was bound to be churned up by large bodies of men and horses.

Most of the French were men-at-arms in full plate armour. There were three lines of them, each six deep, the first two lines dismounted and carrying sawn-off lances. A third line remained mounted, as did two detachments of 500 men-at-arms who were on the wings. They had some cannon and even some catapults together with a few crossbowmen and archers but there was no room to deploy them. The French plan – if plan it can be called – was for the horsemen on the wings to dispose of the English archers, while their men on foot got to grips with the English men-at-arms and overwhelmed them. They hoped that the English would facilitate this simple operation by attacking. Even the Constable d’Albret and Marshal Boucicault took their places in the front rank of the first line. The French therefore left themselves without any proper command structure, let alone any room to manoeuvre.

There was another eye-witness besides Henry’s chaplain who has left an account. This was ‘Messire Jehan, bastard de Waurin, sieur du Forestal’, a Picard nobleman born in 1394 who fought on the French side and whose father and younger brother were killed in the ensuing combat. Waurin recalls what it was like for the French nobles to prepare for battle:

And the said Frenchmen were so heavy laden with armour that they could not support the weight nor easily go forward; firstly they were armed in long steel coats of plate down to the knee or even lower and very heavy, with armour on their legs below, and underneath that white harness [felt], while most of them had on basinets with chain-mail; the which weight of armour, what with the softness of the trampled ground … made it hard for them to move or go forward, so that it was only with great difficulty that they might raise their weapons, since even before all these mischiefs many had been much weakened by hunger and lack of sleep. Indeed it was a marvel how it was possible to set in place the banners under which they fell in. And the said Frenchmen had each one shortened his lance that it might do more execution when it came to fighting and dealing blows. They had archers and crossbowmen enough but would not let them shoot, since so narrow was the field that there was room only for men-at-arms.

5

The English also took up their positions at dawn. They were by now down to 800 men-at-arms at most and probably slightly under 5,000 archers. The former, dismounted and carrying sawn-off lances like the French, were grouped four deep in three ‘battles’, each one flanked by a projecting wedge of archers four or five deep; on both wings there was a horn-shaped formation of archers curving gently forward so that they could shoot in towards the centre. By the king’s orders every archer stuck an eleven foot long stake, sharpened at both ends, into the ground in front of himself as protection against enemy cavalry. There were not enough troops for a reserve, so great was the disparity in numbers, the baggage train behind being guarded by ten men-at-arms and thirty archers. However, the English front did at least cover the entire centre while the flanks were protected by the woods.

Descriptions of Agincourt omit to comment on the relatively advanced age of the men whom the twenty-six-year-old monarch chose as his key commanders for this critical confrontation. The right was under his cousin, Edward, Duke of York, who at forty-two was the senior member of the royal family; fat and extremely cunning, once a favourite of Richard II, he was a natural survivor and by medieval standards in advanced middle age. The left wing was under Lord Camoys, married to Hotspur’s widow, who had seen service against the French as long ago as the 1370s. A still more reassuring figure was ‘old Sir Thomas Erpingham’, Knight of the Garter, who had charge of the archers. Born in 1357 he had been a household man of both John of Gaunt and Bolingbroke, accompanying the latter into exile in 1397 and on his march from Ravenspur to seize the crown. He had become Steward of the Royal Household in 1404 and was someone whom the king had known for most of his life. Henry, as overall commander, took the centre himself. It is significant that he did not entrust one of the main commands to his brother Humphrey – he was plainly anxious to have the coolest and most reliable heads available.

The author of the

Gesta

was among the other chaplains, the sick and the supernumaries who stayed near the baggage. He says that he and his fellow English priests were so frightened that he believed the French to be thirty times larger than the English army, and that he and his companions prayed throughout ‘in fear and trembling’. Nonetheless, he kept his head sufficiently to watch the battle and gives the best eye-witness account of it.

6

Henry heard three Masses and took Communion before donning a burnished armour, over which he wore a velvet and satin surcoat, embroidered in gold with the leopards and lilies; on his helmet was a coronet, ‘marvellous rich’, studded with rubies, sapphires and many pearls. Then, riding a small grey pony – a page leading a great war-horse behind him – he rode up and down the line in front of his troops. His eve-of-battle speech struck a familiar note – he ‘was come into France to recover his lawful inheritance and that he had good and just cause to claim it’. He warned the archers that the French had sworn to cut three fingers off the right hand of every English bowman captured. ‘Sirs and fellows,’ he promised his army, ‘as I am true king and knight, for me this day shall never England ransom pay.’ When he had finished they shouted back, ‘Sir, we pray God give you a good life and the victory over your enemies!’

In the justified belief that it would be best for the English to open the battle, the French remained motionless, some 700 yards away. After waiting for four hours Henry decided that his cold, wet, hungry and weary men had stood there quite long enough and resolved to make the French attack. He ordered Erpingham to take the archers forward just within range of the enemy. When Sir Thomas signalled that he had done so, by throwing his wand of office into the air, the king gave the command, ‘Banners advance! In the name of Jesus, Mary and St George!’ His men therefore, as was their custom, first knelt and kissed the earth on which they made the sign of the cross, placing a morsel of soil in their mouths in token of desire for communion. Then, trumpets and tabors sounding (‘which greatly encouraged the heart of every man’), they marched forward as steadily as the soggy ground permitted, shouting in unison at intervals, ‘St George!’ The little army was now within 300 yards of the vast host of the enemy, many of its men bedraggled and lacking equipment, especially the archers who went barefoot because of the mud. The latter replanted their stakes, a horse’s breast high and angled so as to impale, and began to shoot. Volley after volley hissed up into the air for a hundred feet before descending noisily onto the Frenchmen who kept their heads down beneath the arrow storm – even if few arrows penetrated their expensive plate armour the clatter must have been unnerving.

Now the first line of the enemy, 8,000 strong, began to advance, roaring hollowly from inside their close helmets their traditional war cry of ‘

Montjoie! Saint Denis!

’ At the same time 500 mounted French men-at-arms, led by the Sieurs Guillaume de Saveuse and Clignet de Brébant, charged the English on each flank. The archers repulsed them with ease. Three horses were impaled on the stakes and their riders killed, among them Saveuse. What drove the enemy horse off, however, was arrow fire under which their poor mounts became unmanageable, screaming and bolting back through those advancing on foot. They knocked many over, throwing the line into confusion. They also galloped over their gunners and catapult men, besides trampling down the sparse contingent of French archers and crossbowmen. Their example was contagious – after only one discharge the entire enemy artillery withdrew rather than face English arrows.

The first line of the dismounted French men-at-arms trudged grimly on, often sinking knee-deep into the mud on account of their weight, an exhausting business for a heavily-armoured man. Their ranks included the greatest names of France, royal as well as noble, for among them were the Dukes of Bourbon and Orleans. The English archers shot point-blank at their flanks – armour-piercing range. To avoid the murderous hail the French flinched away towards the centre, bunching up, so that the line turned into a dense scrum. Nevertheless they came doggedly on, though trying to keep away from the wedges of archers between the English battles who were also shooting at them. At last three tightly packed columns of French infantry crashed into the English men-at-arms, with such an impact that the latter were flung two or three yards back.

But the French were packed so close together that they could not raise their arms to use their weapons, while those in front were pushed over by those behind. Once down it was almost impossible for them to regain their feet. The fallen were soon pressed further down by more and more men falling on top of them in ever growing heaps; many drowned in mud or were suffocated by the bodies above. (John Hardyng, a former squire of Hotspur’s who was present, says specifically that ‘more were dead through press than our men might have killed’.) As soon as their arrows were exhausted, the English archers seized ‘swords, hatchets, mallets, axes, falcon-beaks and other weapons’ – even stakes according to the

Gesta

– and rushed at their enemies. Lightly clad, they jumped on top of the prostrate men-at-arms, frequently three deep, to get at their companions. Yet more Frenchmen were pushed off their feet and lost their balance as the second line came up behind.