Henry V as Warlord (24 page)

Read Henry V as Warlord Online

Authors: Desmond Seward

Henry reacted predictably, loudly and cynically lamenting the death of ‘a good and loyal knight and honourable prince’ (a blackly humorous description), while – to judge from the accounts in more or less contemporary chronicles – it was abundantly clear that he realized that he could now obtain almost anything he wanted. Waurin records how he swore that by the help of God and St George he would have the Lady Catherine though every Frenchmen should say him nay. Ten days after the murder Queen Isabeau wrote exhorting him to avenge Duke John and it seems that at the same time she asked Duke Philip to protect her from her son. She knew what Henry wanted and was prepared to co-operate. Negotiations between the English and the Burgundians began at Mantes at the end of October. Henry told the envoys that if their duke tried to take the French crown he would make war on him to the death. He expected to marry Catherine and inherit the crown from King Charles, who however might keep it during his life, while queen Isabeau was to retain her estates. These were the terms which would eventually be agreed by the Treaty of Troyes in April 1420 and make him ‘heir and regent of France’.

Meanwhile at Mantes, according to Tito Livio, the king ‘gave not himself to rest and sloth but with marvellous solicitude and diligence he laboured continually. For almost no day passed but he visited some of the holds, towns and [strong] places. And everything that they needed he enstored. He ordained in all parts sufficient garrisons for their defence. He victualled them. He repaired their castles, towers and walls. He cleansed and scoured their ditches.’

9

He did not neglect to let London know what was happening, writing under his signet on 5 August 1419 to the mayor and aldermen that the enemy would not make peace and that therefore he must continue the war.

A further meeting of Burgundian notables at Arras warned Duke Philip that if he allied with the English there was a danger that not only would Henry drive the king and queen out of France but many of the French people as well, replacing them by English lords, knights and priests; this warning surely reflects the impression made by news of what was happening in Normandy. On the other hand most of Philip’s subjects believed in the dauphin’s guilt and wished that the duke would avenge his father’s murder. Philip was a Valois too, the great grandson of King John II who had been defeated at Poitiers, and it might be asked why he did not put in a bid for the throne himself instead of letting the Englishman take it. But Philip could not fight both the Armagnacs and the English; in any case the latter now had a name for near invincibility. By allying with Henry he doubled his territory and blocked the return to power of the hated faction which had killed his father so foully.

The king’s hold over large areas of France was to be made infinitely more secure by the alliance with Burgundy and by the feud between Burgundians and Armagnacs. Any Frenchman who had little love for the Englishman but feared the Armagnacs was forced to support him. This was particularly true in the capital where, in the light of the bloody massacres of recent years, every Parisian had good reason to dread the return of the dauphin whose Armagnac followers would surely take the opportunity of settling old scores as bloodily as possible. The Bourgeois of Paris shudders as he recounts how the city was full of rumours of fiendish Armagnac atrocities – each report of the dauphin’s forces raiding anywhere in the vicinity of Paris being greeted with horror.

Henry was perversely anachronistic in his insistence on seeing the throne of France as something which was neither more nor less than a personal inheritance. Yet at the same time he was fully aware of the power of nationalism – from his Welsh campaigns and from his English subjects’ frenzied rejoicing at his victories. Sometimes when talking to Frenchmen he even referred to ‘our way’ and ‘your way’. Where, on the other hand, he was centuries before his time was in presenting the dispute over the French throne as a struggle between personalities. No modern politician contesting the leadership of a party or the presidency could have sold his case more shrewdly. He offered himself as an experienced and proven leader, a superb soldier and brilliantly efficient administrator who could give outstandingly good government, impeccably fair justice and, above all, peace. At the same time he contrasted his rival with himself– as an immature degenerate, a murderer rejected by his parents, condemned by the law of the land, the willing tool of vicious and revengeful party bosses.

The King of England realized that he was now the most powerful man in France, against whom no one could hope to stand successfully, and that he was on the verge of a diplomatic triumph. He continued to batter his way mercilessly towards Paris while at the same time mopping up any Norman strongholds which still held out for the King of France. He moved his headquarters from Mantes to Pontoise on 6 August, Clarence raiding savagely up to the very gates of Paris. Gisors, the easternmost strongpoint in Normandy, fell to him on 23 September 1419, and St Germain very soon after; Gisors threatened the Burgundian border, St Germain Paris. The Burgundians might still control the capital but they had to accept that Henry was certain to capture it and that with Paris they would lose their hold over that tattered symbol of phantom authority which was poor, mad King Charles VI. They were forced to accept that their only course was to follow their instinct to avenge Duke John’s killing and ally with the English, however much good reason they had to dislike them. The English king knew that he could demand what he wanted from the Burgundians – their acquiescence in his conquering not merely vast tracts of France but the French crown itself. In early December his troops finally obtained the surrender of Château Gaillard on its great cliff overlooking the Seine. It had been popularly regarded by the French as the strongest fortress in the realm.

Constructive negotiations commenced as soon as the Burgundian envoys arrived at Mantes on 26 October. Despite their being received ‘very benignly and feasted’, Henry repeated what he had told Duke Philip’s father; that unless their master agreed to his terms he would conquer France by himself. This time he set a deadline for agreement – Martinmas, 11 November. He again made clear just what he wanted – there never was a more expert practitioner of

realpolitik

. He demanded the hand of Catherine of France and his recognition as heir to the French throne; while Charles VI might retain the crown till his death, Henry must be Regent of France during his mad fits; and the Duke of Burgundy would have to acknowledge Henry as his sovereign after his crowning. As the English king saw clearly, Philip had much to gain from an agreement; not only would he have the chance of increasing his territory but he would be protected from the dauphin and the Armagnacs. If some Burgundian supporters feared that Englishmen might monopolize all positions of power and influence in France, it was obvious that Henry V would never allow so dangerous a situation to develop. A treaty was signed with Duke Philip on Christmas Day, 1419. All that remained was to persuade the French king and queen to disinherit their son.

The dauphin was accused of killing Duke John on the bridge at Montereau and the accusation was used as a pretext for depriving him of his inheritance. Even had he been tried and found guilty there was no law or precedent for excluding him from the succession, while the notorious insanity of the French king made it impossible for him to set his son aside with any convincing show of legality. Nevertheless, the infuriated Burgundians’ desire for revenge enabled Henry to use the accusation as grounds for usurping the youth’s birthright.

The English king had convinced himself that in creating a dual monarchy, in which each realm would be governed according to its own laws, he was securing what was rightfully his. He believed that he alone could impose the same good government on France which he had given England. His entire political programme was based on these two firm convictions.

Henry tried indefatigably to surround dauphinist France with a string of diplomatic alliances, some of them dynastic. Excellent, although not particularly profitable, relations were maintained with the Emperor Sigismund, while the three important Elector-Archbishops of Cologne, Triers and Mainz all received English subsidies. A trade agreement was negotiated with Genoa.

The king also tried, unsuccessfully, to marry his brother Humphrey of Gloucester to the daughter of Charles III of Navarre, whose realm adjoined Guyenne. His most ambitious attempt at a dynastic alliance was in 1419 when he sent John Fitton and Agostino de Lante to Naples to explore the possibility of his brother John of Bedford being adopted by the Neapolitan queen. Bedford was thirty while Joanna II was forty-four, a widow with a discarded second husband. She was childless and clearly infertile, a byword for promiscuity and had a thoroughly sinister reputation. She had made the first move in the negotiations, offering to create Bedford Duke of Calabria – the title traditionally borne by heirs to the Neapolitan throne – and to acknowledge him as her official successor, besides handing over to him all citadels and castles in her possession. Probably just as well for Bedford, nothing came of this exotic project.

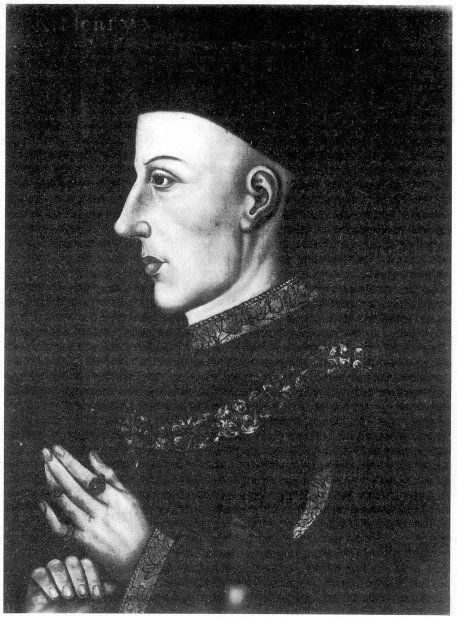

Henry V as a youth. From an early sixteenth-century copy of a lost original. (The Mansell Collection)

John, Duke of Bedford kneels before St George, from the

Bedford Book of Hours

c. 1423. The small forked beard makes it highly probable that St George is a portrait of Henry V. (The British Library)

Thomas Montacute, Earl of Salisbury – Henry’s most formidable commander – with fashionable military haircut. Note his poleaxe. (The British Library)

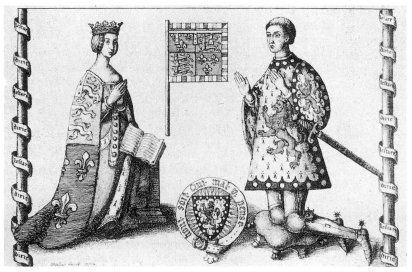

Henry V’s aunt Princess Elizabeth Plantagenet and her third husband, Sir John Cornwall KG, one of his most daring commanders. From a window formerly at Ampthill in Bedfordshire.