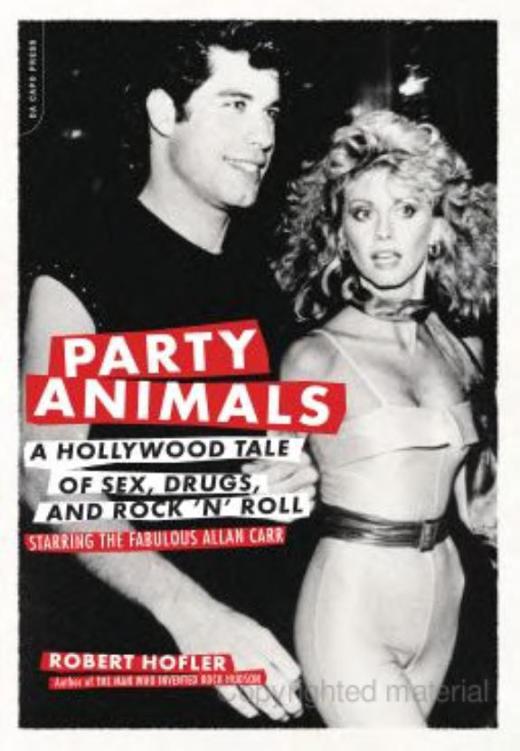

Party Animals: A Hollywood Tale of Sex, Drugs, and Rock 'N' Roll Starring the Fabulous Allan Carr

Authors: Robert Hofler

Tags: #General, #Performing Arts, #Biography & Autobiography, #Reference, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #Social Science, #Film & Video, #Art, #Popular Culture, #Individual Director

BOOK: Party Animals: A Hollywood Tale of Sex, Drugs, and Rock 'N' Roll Starring the Fabulous Allan Carr

6.34Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

Table of Contents

ALSO BY ROBERT HOFLER:

The Man Who Invented Rock Hudson

Variety’s

“The Movie That Changed My Life”

“The Movie That Changed My Life”

INTRODUCTION

And the Phone Rang

July 5, 1999. The phone call came early that Sunday morning.

“Can you see the house today?” the real estate agent asked. “It’s the Ingrid Bergman house. She used to live there. I think it’s exactly what you’ve been looking for. It goes on the market tomorrow, Monday. But I can show it to you today

exclusively

.”

exclusively

.”

Brett Ratner assured his realtor, Kurt Rappaport, that he would be right over. He wrote down the address: 1220 Benedict Canyon Drive. The house was available, suddenly, because someone had died, suddenly. Someone named Allan Carr, said Rappaport.

Ratner wondered: Could it be

that

Allan Carr? The very same Allan Carr who produced the top-grossing movie musical of all time,

Grease,

as well as the most absurd movie musical of all time,

Can’t Stop the Music

starring the Village People in their first and last big-screen appearance? Was this the party-central house that Ratner read about as a kid—this virtual pleasure arcade of 1970s hedonism that rivaled Hugh Hefner’s Playboy mansion—that is, until 1980s reality hit hard and Allan Carr produced what Hollywood vets were still calling the worst, most embarrassing Oscars telecast ever? Was he about to enter the Beverly Hills home of Allan “you’ll-never-throw-another-party-in-this-town-again” Carr?

That

Allan Carr?

that

Allan Carr? The very same Allan Carr who produced the top-grossing movie musical of all time,

Grease,

as well as the most absurd movie musical of all time,

Can’t Stop the Music

starring the Village People in their first and last big-screen appearance? Was this the party-central house that Ratner read about as a kid—this virtual pleasure arcade of 1970s hedonism that rivaled Hugh Hefner’s Playboy mansion—that is, until 1980s reality hit hard and Allan Carr produced what Hollywood vets were still calling the worst, most embarrassing Oscars telecast ever? Was he about to enter the Beverly Hills home of Allan “you’ll-never-throw-another-party-in-this-town-again” Carr?

That

Allan Carr?

In addition to its illustrious, and sometimes infamous, film-world pedigree, the house at 1220 Benedict Canyon Drive carried an evocative, cypress-scented name. Hilhaven Lodge rested on the side of a steep hill a mere mile from where Ratner had recently taken up residence, at the legendary Beverly Hills Hotel

on Sunset Boulevard and Crescent. He could walk there in half an hour, but since this was Beverly Hills, the custom dictated that he drive. And besides, he could get there faster if he took his Bentley.

on Sunset Boulevard and Crescent. He could walk there in half an hour, but since this was Beverly Hills, the custom dictated that he drive. And besides, he could get there faster if he took his Bentley.

In Billy Wilder’s last film, a 1978 box-office disaster called

Fedora,

William Holden plays Wilder’s stand-in: an old-time movie producer, who, because he can’t finance his latest opus, is forced to complain, “The kids with beards have taken over! Just give them a hand-held camera with a zoom lens!”

Fedora,

William Holden plays Wilder’s stand-in: an old-time movie producer, who, because he can’t finance his latest opus, is forced to complain, “The kids with beards have taken over! Just give them a hand-held camera with a zoom lens!”

Wilder, of course, was referring to such hirsute, relatively young upstarts at the time as Francis Ford Coppola and Steven Spielberg and Martin Scorsese and George Lucas, who had revolutionized the entertainment industry. But twenty years later, it was the boyish and brash Brett Ratner who sported the big beard and the even bigger box-office success,

Rush Hour,

starring Chris Tucker, a stand-up comic with few Hollywood credits, and Jackie Chan, a martial-arts star from Hong Kong with absolutely no Hollywood credits. That cop comedy made back its $33-million budget in its first weekend and went on to gross five times that much. Sometime around that film’s second month of release, when

Rush Hour

hit the almighty $100-million mark, Ratner moved into the Beverly Hills Hotel and promptly began to think about realizing his dream of living in an old Hollywood house. And not just any old Hollywood house. He didn’t want, for instance, Norma Desmond’s mansion on Sunset Boulevard, to bring this story back to Billy Wilder. That manse, which actually stood across town in Hancock Park before it was unceremoniously plowed under to make way for a much-needed filling station on Wilshire Boulevard, looked too monstrously Gothic by half. Ratner didn’t want Nathaniel West’s idea of Hollywood grandeur gone bad. Ratner wanted a place like Woodland, Bob Evans’s estate, where Greta Garbo once slept and, momentarily, achieved her ultimate dream “to be alone.” The

Rush Hour

director recently attended a party at the

Chinatown

producer’s sixteen-room house, and had fallen in love with its understated French Regency style.

Rush Hour,

starring Chris Tucker, a stand-up comic with few Hollywood credits, and Jackie Chan, a martial-arts star from Hong Kong with absolutely no Hollywood credits. That cop comedy made back its $33-million budget in its first weekend and went on to gross five times that much. Sometime around that film’s second month of release, when

Rush Hour

hit the almighty $100-million mark, Ratner moved into the Beverly Hills Hotel and promptly began to think about realizing his dream of living in an old Hollywood house. And not just any old Hollywood house. He didn’t want, for instance, Norma Desmond’s mansion on Sunset Boulevard, to bring this story back to Billy Wilder. That manse, which actually stood across town in Hancock Park before it was unceremoniously plowed under to make way for a much-needed filling station on Wilshire Boulevard, looked too monstrously Gothic by half. Ratner didn’t want Nathaniel West’s idea of Hollywood grandeur gone bad. Ratner wanted a place like Woodland, Bob Evans’s estate, where Greta Garbo once slept and, momentarily, achieved her ultimate dream “to be alone.” The

Rush Hour

director recently attended a party at the

Chinatown

producer’s sixteen-room house, and had fallen in love with its understated French Regency style.

With fewer than half as many rooms, Hilhaven Lodge was far less grand than Evans’s Woodland but more storied in movie history, because Ingrid Bergman (and Kim Novak, too) didn’t just sleep there. She owned the joint. Ratner could only hope that Bergman’s extraordinary talent for acting extended to picking houses. As he was soon to learn,

Gone with the Wind

producer David O. Selznick bought the Benedict Canyon house for Bergman when he feared that his moody Scandinavian star might return with her husband, Dr. Petter Lindstrom, to Sweden. As his gift of enticement to make Bergman stay put in Hollywood, Hilhaven Lodge made good business sense for Selznick, despite the

reported $40,000 price tag. With Ingrid happily living there, he could continue to loan his star to other studio chiefs for four times the amount he was paying her in 1944.

Gone with the Wind

producer David O. Selznick bought the Benedict Canyon house for Bergman when he feared that his moody Scandinavian star might return with her husband, Dr. Petter Lindstrom, to Sweden. As his gift of enticement to make Bergman stay put in Hollywood, Hilhaven Lodge made good business sense for Selznick, despite the

reported $40,000 price tag. With Ingrid happily living there, he could continue to loan his star to other studio chiefs for four times the amount he was paying her in 1944.

Although the address reads 1220 Benedict Canyon Drive, Hilhaven Lodge anchors itself not on that serpentine road but rather at the top of a cul-de-sac that runs off the east side of the drive and up a narrow evergreen corridor to the house. Racing along Benedict Canyon Drive, Ratner nearly missed the turnoff on the right that leads to this cozy enclave of three addresses, one of which is the Ingrid Bergman house. That’s what Rappaport called it, “the Ingrid Bergman house,” although its present owner was a man named Allan Carr, who, at this point in his life, was as dead as the Swedish movie star had been for the past sixteen years.

It was a legendary house, because legendary things had happened there to legendary people.

Beyond the gate, the driveway makes a steep upgrade to the house on the hill and its adjacent cottage. It was here on the driveway that Ingrid Bergman, in typical Hollywood style that was so atypical for this otherwise introspective Swede, rolled out a thirty-foot red carpet to welcome her future paramour, director Roberto Rossellini, to the West Coast in 1946. She admired his films

Open City

and

Paisan,

destined to be classics of Italian neorealism, and when that latter title won the New York Film Critics award for best foreign film, he cabled her in mangled English I JUST ARRIVE FRIENDLY, to which she cabled back WAITING FOR YOU IN THE WILD WEST. They would make five beautiful movies together and nearly as many beautiful babies.

Open City

and

Paisan,

destined to be classics of Italian neorealism, and when that latter title won the New York Film Critics award for best foreign film, he cabled her in mangled English I JUST ARRIVE FRIENDLY, to which she cabled back WAITING FOR YOU IN THE WILD WEST. They would make five beautiful movies together and nearly as many beautiful babies.

By the time Ratner first saw Hilhaven Lodge, the red carpet had long been rolled up and a yellow Mercedes-Benz now occupied the driveway. It carried a curious designer license plate: CAFTANS. Ratner walked up the flight of flag-stone steps to the front door. Built of chiseled fieldstone and redwood, the house came topped with a wood-shingle roof and looked like a hunting lodge out of

Rebecca

or some other Daphne du Maurier novel set in Cornwall-on-the-Pacific. To Ratner’s immediate right on the grounds, the rectangular pool came courtesy of Dr. Lindstrom, but the small stone cottage nestled beside it was very much part of the lot’s original 1927 design. If Rossellini had been impressed, or more likely dumbfounded, by the red carpet, it was the cottage by the pool that won his heart: It was here that his affair with Mrs. Lindstrom began shortly after the Italian director’s benefactor, producer Ily Lopert, stopped paying his bills at the Beverly Hills Hotel and Dr. Petter Lindstrom invited Rossellini to live free

of charge on the grounds near the big house, which Ingrid affectionately called “the barn.”

Rebecca

or some other Daphne du Maurier novel set in Cornwall-on-the-Pacific. To Ratner’s immediate right on the grounds, the rectangular pool came courtesy of Dr. Lindstrom, but the small stone cottage nestled beside it was very much part of the lot’s original 1927 design. If Rossellini had been impressed, or more likely dumbfounded, by the red carpet, it was the cottage by the pool that won his heart: It was here that his affair with Mrs. Lindstrom began shortly after the Italian director’s benefactor, producer Ily Lopert, stopped paying his bills at the Beverly Hills Hotel and Dr. Petter Lindstrom invited Rossellini to live free

of charge on the grounds near the big house, which Ingrid affectionately called “the barn.”

Rappaport greeted Ratner at the barn’s front door, and after the potential buyer took one step inside the foyer, he succumbed to a severe case of décor whiplash. The charming hunting-lodge façade gave way immediately to froufrou white lattice, gold mirrors, a grotto-like stone fountain, and an altar of sorts that featured a silver-framed portrait of Ingrid Bergman, circa

Notorious.

Ratner stepped closer to read the inscription:

Notorious.

Ratner stepped closer to read the inscription:

To Allan,

I’m glad to see the Swedes are still paying for this house.

Love, Ingrid

Allan Carr and Ingrid Bergman. Never had one Hollywood residence linked two more disparate personalities. How ever had the ebullient Jew from Illinois gotten the cool Swede from Stockholm to inscribe her own photo? Less of a mystery were “the Swedes” who paid for the house. In addition to Bergman, there was Ann-Margret, the erstwhile kitten with a whip whom Allan Carr had groomed from Las Vegas stardom to Oscar-nominated film glory, if, in fact, rolling around in a small mountain of baked beans and screaming “Tommy” was anyone’s idea of glory.

With Rappaport pointing out the architectural details, Ratner’s aesthetic disorientation continued to spin his bearded head around and around. As he would later observe, “The bones of the house were solid, but Allan Carr kept peeking out.”

As in life, and now in death, nobody could miss him.

At Hilhaven, the low-ceilinged foyer leads to an explosion of space in the living room. No wonder Ingrid had nicknamed it “the barn.” A vast beamed and vaulted room, its peak rises to an awesome thirty feet, and straight ahead, the granite fireplace with its old scroll inscription HILHAVEN LODGE could have been lifted from

Citizen Kane

’s Xanadu. To the right, a sweeping bay window with an equally extensive window seat offers a panoramic view of the pool and cottage. No doubt about it, thought Ratner: This is classic, elegant Hollywood architecture. But what about the chandelier that dripped crystal over a Lucite grand piano, and high above it, as if ready to swing through the oak rafters, a life-size portrait in painted plywood, by Gary Lajeski, of the recently departed master of Hilhaven Lodge—Allan Carr himself!—his avoirdupois badly disguised

in a signature caftan as the breeze wafts through shaggy blond-streaked hair, his plump left hand placed in proud ownership over a violet-filled urn? Allan must have posed for the portrait at the pool outside, as if he were the reincarnation of Hadrian on a summer retreat to Capri—or was it Mykonos?—with the guys. In case anyone didn’t know the once proud owner of Hilhaven, there was another Allan Carr portrait, this one in oil on canvas, placed in honor over the bay window. It showed a somewhat younger and slimmer man, this one decked out in white suit and Jew-fro.

Citizen Kane

’s Xanadu. To the right, a sweeping bay window with an equally extensive window seat offers a panoramic view of the pool and cottage. No doubt about it, thought Ratner: This is classic, elegant Hollywood architecture. But what about the chandelier that dripped crystal over a Lucite grand piano, and high above it, as if ready to swing through the oak rafters, a life-size portrait in painted plywood, by Gary Lajeski, of the recently departed master of Hilhaven Lodge—Allan Carr himself!—his avoirdupois badly disguised

in a signature caftan as the breeze wafts through shaggy blond-streaked hair, his plump left hand placed in proud ownership over a violet-filled urn? Allan must have posed for the portrait at the pool outside, as if he were the reincarnation of Hadrian on a summer retreat to Capri—or was it Mykonos?—with the guys. In case anyone didn’t know the once proud owner of Hilhaven, there was another Allan Carr portrait, this one in oil on canvas, placed in honor over the bay window. It showed a somewhat younger and slimmer man, this one decked out in white suit and Jew-fro.

The living room contained only a few pieces of nondescript furniture. It was, after all, a party house to be filled with famous people, not intimate conversations, and expensive tchotchkes. But if the now-deceased owner of Hilhaven Lodge had skimped on sofas and chairs, he made up for it with a stunning display of Lalique and Baccarat crystal that sent the room swirling with light that reflected off dozens of photos under silver frames, most of which featured Allan with the stars he’d managed over the years—entertainers like Peter Sellers, Mama Cass Elliot, Rosalind Russell, Sonny Bono, Dyan Cannon, Tony Curtis, Petula Clark, Herb Alpert, Marvin Hamlisch, Joan Rivers, Marlo Thomas, and Melina Mercouri, as well as a wide range of personalities who made sense only as a Dadaist collage: Sophia Loren, Che Guevara, John Travolta, Mae West, Placido Domingo, Jayne Mansfield, Ronald and Nancy Reagan, the Village People, and Roy Cohn. “There were more photos of Roy Cohn than you can believe,” Ratner would later note. Or, as Allan Carr himself used to put it, “Walk around the house and you’ll see my life on the shelves.”

Other books

A Simple Suburban Murder by Mark Richard Zubro

Cheating to Survive (Fix It or Get Out) by Christine Ardigo

Perfect Together (Canyon Cove Book 5) by Liliana Rhodes

Silence 4.5 by Janelle Stalder

Death in the Time of Ice by Kaye George

This is For Real by James Hadley Chase

Live In Position by Sadie Grubor

A Duchess to Remember by Christina Brooke

Hammer Head: The Making of a Carpenter by Nina MacLaughlin