Hetty Feather (11 page)

Authors: Jacqueline Wilson

We stared back at her earnestly, tipping our chins

up and stretching our necks. She gave us each a warm

kiss on the lips and then took us by the hand.

'Come then, my children.'

We emerged into the loud, hissing bustle of the

station. Mother led us outside, where the hansom

cabs were waiting.

'Please take us to Guilford Street,' said Mother,

fingering her fat purse to show she could pay the

fare.

'The Foundling Hospital?' said the cab driver.

He sucked his teeth and shook his head at us. 'Poor

little mites.'

We clambered inside his cab and peered out in

awe and terror at the crowded London streets.

Mother might have been a country woman, but she

proudly showed us St Paul's Cathedral as we passed

slowly over Waterloo Bridge. We could not believe

the traffic everywhere. We were used to seeing one

cart at a time in the village lanes. There seemed to be

hundreds

of cabs and carriages and carts and huge

omnibuses crowded with city folk. Men in smart dark

suits marched on foot over the bridge. I wondered

if they could be some strangely garbed army, but

Mother said they were simply businessmen on

their way to and from work. There were ladies

too, their skirts drawn up in comical bustles at the

back, trit-trotting in their tiny shoes. They had to

hold up their skirts and tread warily when they

crossed the streets, which were covered in horse

dung.

We were country children and used to horse

dung –

and

clearing out the pigsty – but we'd never

smelled it so strongly before. The river smelled sour

and strange too, with a greasy slick shining in the

water. What sort of city was this where you couldn't

stroll along the streets or swim in the river?

Once we were over the bridge, the cab travelled

through such a muddle of streets, some very broad

and big, some narrow twisting alleyways, so that

I was hopelessly muddled and confused. My heart

thudded whenever I spotted any great grey building

in case it was the hospital. At last the cab slowed and

came to a stop outside great iron gates enclosing a

plain wide building with many arched windows.

Mother drew in her breath and clutched our

hands tight. She didn't need to tell us. We were at

the Foundling Hospital.

Gideon and I huddled in the cab. Mother had to

pull us out.

'Please be so good as to wait,' she said to the

cabman, and approached the porter. 'If you please,

sir, I'm bringing my two foster children back to the

hospital,' she said.

He nodded and let us through the forbidding gates.

Mother walked us along the long gravel path

towards the doorway. We stared up at all the windows

but we couldn't see inside. There were no children

peeping out at us, no children playing on the grass,

no children anywhere. I strained my ears but could

hear no chatter, no singing, no laughter.

Mother rang the doorbell, and a tall woman in

a dark dress and white apron opened the door. She

had a white cap tied on her head and a long grim

face. She did not smile.

'Foundlings 25621 and 25629?' she said.

'Yes, ma'am,' said Mother huskily. 'This is Gideon

Smeed and Hetty Feather. They are such dear

children. Hetty is very bright indeed, and Gideon is

very good and loving, though he doesn't speak just

at present. He needs a little extra cosseting—'

'We treat all our foundlings in exactly the same

manner. We have no favourites here,' said the nurse.

'Come along, children.'

She held out her hands. We shrank backwards,

clutching Mother.

'Say goodbye,' the nurse said firmly.

I was struck as dumb as Gideon. I couldn't believe

it was actually happening. Not now, not so coldly

and quickly.

Mother gathered us together and kissed us, first

me, then Gideon. 'Goodbye, my dear lambs. Try to

be good and make me proud of you,' she whispered.

'Hetty, look after your brother.'

She straightened up and took a step backwards.

Then she turned and ran down the path, her hand

over her eyes.

'Mother!' I called.

Before she could look back the nurse shut the

door, trapping us inside the hospital. She clasped our

hands determinedly. Her own hands were icy cold

and startlingly smooth – we were used to Mother's

big work-roughened hands.

'I am Nurse Beaufort. Come with me,' she said,

setting off at a quick march.

We had to scurry fast to keep up with her. Gideon

tripped once and she jerked his arm impatiently,

hurting him. He started crying then, big tears

splashing down his cheeks.

'Don't cry so, Gideon. I am here. I will look after

you,' I said desperately.

'Ssh, child. You are not allowed to talk until outdoor

playtime,' said the nurse, yanking my arm too.

She pulled us up a long flight of stairs. There

was another nurse standing there, waiting. She

was dressed in an identical dark frock and white

starched apron, but she was smaller and very squat.

Her dress strained at the seams and her white cap

seemed too small for her dark-pink face. She had

little eyes, prominent nostrils and several chins,

looking for all the world like a pig in a bonnet. I

gave a little snort, half laughing, half crying.

'Be quiet, child,' she snapped. She seized me by

the shoulders and propelled me to the right. My

head jerked round. Tall, grim Nurse Beaufort was

propelling Gideon

the other way.

'Oh no, if you please, Nurse, Gideon and me, we

have to stay together!' I said, struggling.

'I am not a nurse! I am Matron Peters. Now come

along,

child. You cannot go with your brother. The

small girls' wing is

this

way,' said Pigface Peters.

'But you don't understand! He's only little. He

can't manage without me.'

'Nonsense.'

'It is

not

nonsense!' I shouted, stopping in my tracks.

'I have to look after Gideon. I promised Mother.'

'You must forget all about your foster mother

now. You are a foundling child and you will obey

our

rules. Our boys and girls live separately – and so

will you.'

'Then let me say goodbye to Gideon! Let me

explain to him. Oh

please

!'

'Stop this ridiculous fuss this instant, Hetty

Feather!'

'I

won't

stop! You are very cruel and wicked and

I hate you!' I cried.

I twisted my wrist out of her grasp and ran the

other way, after Gideon.

'Gideon! Oh, Gideon!' I shouted.

He was dragging his feet and drooping, his boots

barely supporting him. He looked round, his eyes

wide, his mouth a great O of terror.

Then fat pig-trotter fingers seized me by the

shoulders. She hauled me along, kicking and

screaming, marching me to the right, away from my

poor brother.

'How

dare

you behave so atrociously! You will be

sorry, my girl, very sorry.'

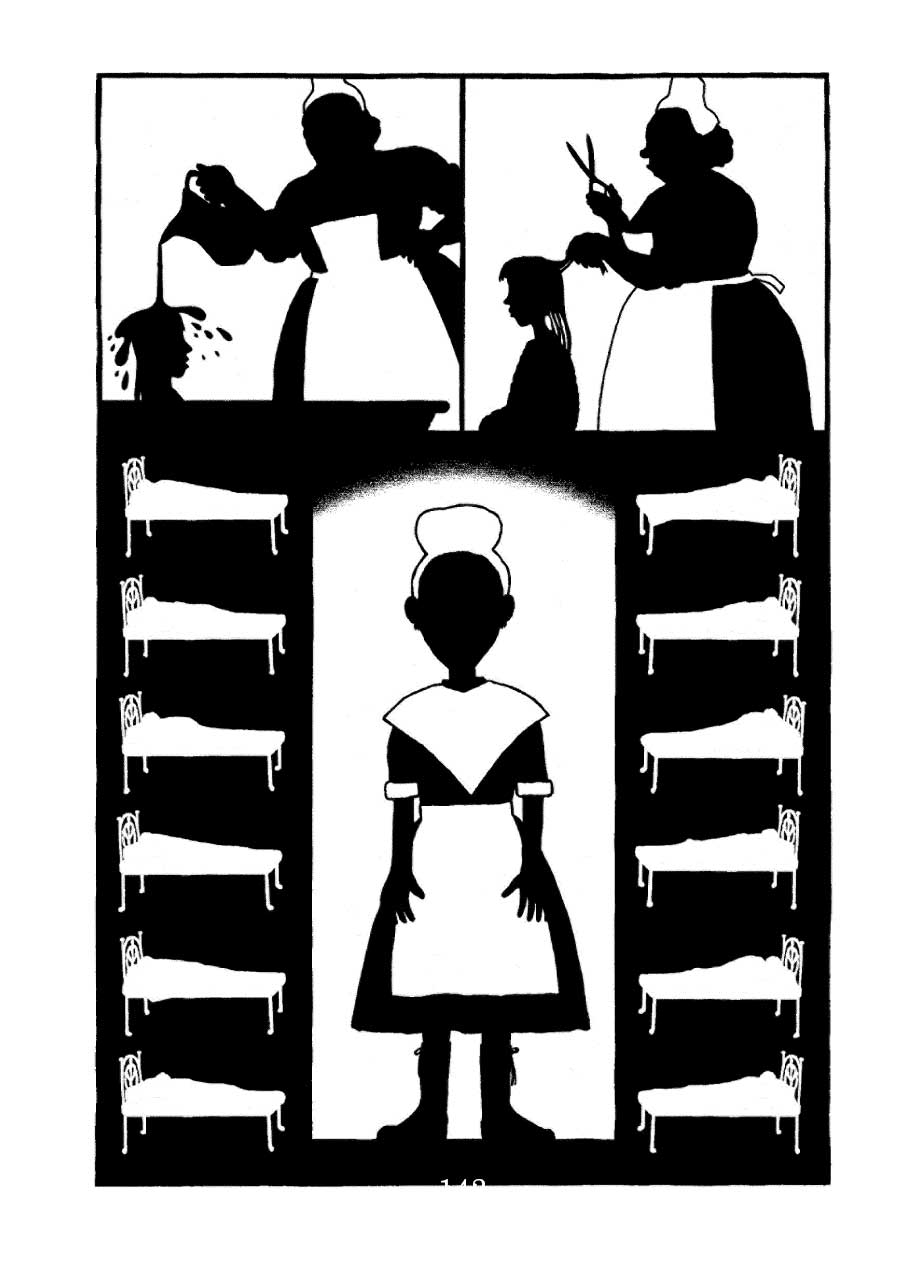

She pushed me into a strange cold room with

small bathtubs in orderly rows.

'Right, missy, take your clothes off instantly. You

need a bath.'

I stared at her. 'But I've

had

a bath. I'm clean as

clean, look!'

'Country

clean,' she said scornfully. 'You need a

good scrubbing to get rid of all those nasty bugs and

beasties. Get those clothes off while I fill the tub.'

I took off my coat and then sat down to start

unlacing my boots. The matron crumpled my

good coat up into a little ball and dropped it into a

basket. I gave her one boot and she threw it on top

of my coat, careless of the muddy soles. She saw my

shocked expression.

'You won't need these any more,' she said, giving

the basket a contemptuous shake.

I blinked at her. Were the foundling children

required to run around

naked?

'You will wear our uniform now,' she said.

'Can I wear my best clothes on Sundays, miss?'

'You must call me

Matron.

No, you wear your

white tippets and aprons on the Sabbath, with

bands around your cuffs, specially snowy white. And

woe betide you if you get them dirty. Now hurry

up,

child. Get the rest of your clothes off and step into

the bath this instant.'

While she was topping up the bath, her back

turned, I took Jem's precious sixpence out of my

pinafore pocket. I stuck it inside my mouth for

want of a better place to hide it. The coin tasted

unpleasantly metallic and felt as big as a dinner

plate against my cheek, but it couldn't be helped.

I was right to be so cautious. Once I had my

pinafore and dress and drawers off, standing

shivering in my shift and stockings, the matron

darted at me, snatched my rag baby and threw her

in the basket too.

'She's not clothes! She's my baby!' I protested,

though it was hard to talk distinctly with the

sixpence wedged in my cheek.

'It's nasty and dirty. And you're not allowed

dollies here.'

'But I can't sleep without her!'

'Then you will have to stay awake,' said the

matron.

She pulled the shift over my head, plucked my

stockings from my feet, lifted me up and plunged me

into the bath. Then she took a cake of red carbolic

soap and started scrubbing me viciously. I wriggled

and squirmed at the indignity, especially when she

started washing my long hair, digging her fat fingers

into my scalp and kneading it as if my head was a

ball of dough. I put my hands up, trying to protect

my poor head. My fingers scratched her wrists and

she dug harder, furious.

'Keep still, you fiery little imp,' she said, lathering

me into a foam. She fetched another jug to rinse

the suds away. 'This will quench that fire!' she said,

pouring icy cold water over me.

I gasped in shock and would have screamed at

her, but I had to keep my mouth stoppered because

of the sixpence. Then she hauled me out onto the

cold floor and wrapped a thin towel round me.

'Well, dry yourself, child, hurry up, hurry up!'

When I was halfway dry she sat me on a stool and

picked up a pair of scissors. I started trembling. What

did she intend to do now? Cut off my fingernails?

Cut off my

fingers?

She attacked my head with a hairbrush,

smoothing out all the tangles so that my hair fell

in a silky curtain past my shoulders – and then she

started snip-snip-snipping, cutting my hair off right

up to my ears.

'Oh,

please

don't cut my hair!' I begged, but she

paid no heed. She snipped until my hair was shorter

than a boy's and I was covered in damp red tendrils.

She brushed them off me with the towel and then

fetched another basket, the clothes inside this one

neatly folded.

'This will be your clothes basket, Hetty Feather.

You are to keep your clothes in it at night, and woe

betide you if you rumple them.'

She pulled out boots and stockings and bade me

put them on. The stockings were stiff and bunched

at the toes with repeated darning, and the boots

were much too big for my small feet. I told Matron,

but she didn't appear to care.

'Put your dress on now – the

right

way round,

you silly child. I will tie your apron for you.'

I hesitated. Where were my new undergarments?

I saw something white in my basket, but it was

simply a strange old-fashioned cap. There was no

shift, no drawers, nothing!

I sidled over to my old clothes.

'Leave them alone! They're going to be disposed

of straight away.'

'But, miss – Matron – I have no drawers!' I

said, agonized.

The matron's pig face went even pinker. 'You do

not wear such garments here,' she said. 'Now put

that dress on at once.'

I stuck my poor shorn head through the stiff brown

serge. It felt hard and scratchy against my scrubbed

skin. She did up my buttons at the back for me, tied

on the apron, and then stuck the cap upon me.

'There!' Matron marched me over to a speckled

mirror above the stone slab sinks. 'Respectable at last!'

I stared at the forlorn figure in the mirror. Was

that weird little creature in the cap really me? I

shook my head violently, but the girl in the mirror

shook her head back at me.

'Now you will join the other infant girls. Come

with me.'

I hung back, fidgeting. 'Please, miss – Matron – I

need the privy,' I blurted.

She consulted the watch pinned to her chest.

'The infant relief break is not for another hour. You

will have to wait.'

'But I need to go

now

! Please, I'm nearly

wetting myself!'

She sighed impatiently. 'The privies are outside in

the yard. I'm not trailing you all the way there. You

will have to use a chamber pot. Go in that little room

and be quick about it. You must learn to control your

bladder as well as your temper, Hetty Feather.'

I ran into the room, selected an ugly pot and sat

on it, trembling. What sort of a madhouse was this?

I put my fingers up under my cap and felt the shorn

ends of my hair. I gave a little sob. Even if I managed

to run away back to Jem, maybe he wouldn't love

me any more because I looked such a fright.

'Hurry up, child!' Pigface grunted outside.

Safe behind the door, I took the sixpence out of

my mouth, stuck out my tongue and waggled it at

her. Then I hid the sixpence in my new tight cuff

and jumped up from the pot.

'Now wash your hands!' she said as I came out

of the little room. 'Dear goodness, do you know

nothing of hygiene?'

I didn't think it at all hygienic to run around

without underwear. I wondered if the matron

wore drawers herself. I imagined her big piggy-pink

bare bottom.

'What are you smirking at?' she said suspiciously.

I lowered my eyes and shook my head. 'Nothing,

Matron.'

'Then come along with me. You will join your

class at their afternoon tasks.'

She took hold of me by the wrist. I looked back

at the little basket of my Sunday clothes, so lovingly

washed and pressed by Mother. They were all in a

muddy jumble now, my poor rag baby sprawling on

top, arms and legs akimbo.

'Come on! You've no need of those nasty old

clothes any more, I've told you that already,' said

Matron Pigface.

'Mayn't I just kiss my baby goodbye?' I begged.

'I've never heard such nonsense. It's only a

bundle of rags!' she said, and she would not let me.

I pictured my poor baby so forlorn without her

mother. I heard her wailing, abandoned in the

basket. I wished she was little enough to hide about

my person, like the sixpence. But there was nothing

I could do. I had to leave her there, tumbled about

in my clothes. I never saw her again.

As Matron Pigface marched me along to my class,

I thought at least I would meet up with Gideon again

– but there was no sign of him. I was thrust into a

room of some forty or fifty girls of five or six or seven,

but there was not a single little boy. The girls were

sitting at small wooden desks, all startlingly similar

in their white caps and mud-hued dresses. They

all stared hard at me and then whispered. I shifted

from one sorely-shod foot to the other, feeling so shy

and strange.

'This is Hetty Feather,' said Pigface.

Several of the little girls giggled. My hands

clenched into fists.

'Thank you, Matron Peters,' said a starch-

aproned nurse at the front of the class. She wasn't

pink and pig-faced, she wasn't grim and pale.

This

nurse had rosy cheeks and dimples and wisps of

curly hair escaping from her cap. She was as sweet

and fresh-faced as Rosie or Eliza or any of the village

girls. She smiled at me.

'I would watch this one. She's got a

very

contrary

way with her. Redheads are always little vixens,'

said Matron Pigface Peters. 'She needs that temper

quelled. Spare the rod and spoil the child, remember!'

She shorted, and then waddled out of the room, her

stays creaking loudly.

'Hello, Hetty dear,' said this new nurse, beckoning

to me.

I crept up to her desk. I saw a leather strap lying

across it. Oh Lordy, was she about to punish me

already?

No, she leaned towards me and said gently, 'Do

not look so fearful, child. It must seem very strange

your first day here, but I promise you will soon get

used to life at the hospital. You seem very small. Are

you turned five yet?'