Hetty Feather (9 page)

Authors: Jacqueline Wilson

'I'm not taking you back to the circus.'

'Then I will go by myself.'

'If you try to do that you will get lost. You are

too little to find the way. It will kill Mother if she

loses another child. And Father will most likely kill

you

if he finds you – and me, into the bargain. Now

lie down properly and go back to sleep like a good

little girl.'

He forced me down on my pillow but I couldn't

sleep, though I tried hard to seek refuge in my

dreams. Eventually I heard Father getting up for

work. I slid out of bed quickly and caught him as he

went down the stairs.

'Why are you up so early, little minx?' he asked.

'I couldn't sleep, Father,' I said.

'I'm not surprised. I dare say this whole circus

escapade was all down to you, Hetty. You have a

knack for leading the others astray. Jem's a sensible

lad but he's soft as butter where you're concerned.'

Father shook his head at me. 'I don't know what

to do with you, child. Perhaps it's just as well you

won't be with us much longer.'

I felt as if Father's huge fist had punched me

straight in the stomach.

'Yes, well might you hang your head,' he said.

'That little lad in my bed was a hair's breadth from

death when we found him. He's still icy cold for all

he's swaddled in shawls like a newborn babe.'

I dodged round Father and ran into his bedroom.

Mother was lying in bed, propped up on one elbow,

crooning a lullaby. Gideon was in a little huddle

beside her. I edged towards him, expecting to see

a little Jack Frost brother, hair hoary white, icicles

hanging from his nose and chin. But Gideon looked

almost his usual self, though he was very pale.

I climbed up into bed beside him. Mother put her

finger to her lips, frowning at me. She clearly wanted

Gideon to sleep – but his dark eyes were wide open.

'Hello, dear Gideon,' I whispered. 'Are you

better now?'

Gideon didn't seem able to tell me. His mouth

opened and moved but no sound came out.

'I can't hear you,' I said, nuzzling closer, so that

my ear was inches from his face.

'Hetty, Hetty, don't squash him! Go back to your

own bed,' said Mother.

'But I—'

'I! I! Can't you think of anyone else but yourself,

child?' said Mother sharply.

Gideon whimpered at her tone.

Mother glared at me. 'See, you're upsetting your

brother. Go

away

!'

All right, I thought. I

will

go away. You don't want

me. Father doesn't want me. Even Jem has had

enough of me. You're all sending me to the hospital

soon anyway. So I'll go away now and save you

the trouble.

I stomped out of Mother's bedroom and then

crouched at the top of the stairs, tucking my knees

up under my nightgown and rubbing my cold feet.

I longed for a warm jacket and my boots, but they

were in my bedroom and I knew Jem would be

suspicious if he saw me putting them on. I took

Gideon's boots instead, lying on the landing, still

caked with mud and grass from his trek into the

forest. They were too big for me but it couldn't be

helped. I had difficulty with the laces. I was used

to Jem helping me tie neat bows, but I turned and

twisted them until they held fast.

I waited, shivering, until I heard Father shut the

front door on his way to the farm. I couldn't count

beyond ten but I had some idea of time and waited

several minutes until I judged it safe. Then I tiptoed

downstairs as best I could in my ill-fitting boots. I

grabbed a hunk of bread from the larder, and wound

an old sack about my shoulders in lieu of a coat. I

could not yet write, apart from my name, so I did

not leave them a note. I felt a pang for not saying

goodbye to Jem, but it couldn't be helped.

I went out the front door, and marched off to join the circus

and my true mother.

Oh dear, I am shaking now as I write this. I did

not get lost. I was only five then, but I was a very

determined child. I hurried through the village,

glad that most folk were still in their beds because

I looked a queer sight in my sacking and borrowed

boots. I could not wait for my own dear mother,

Madame Adeline, to clothe me in some beautiful

pink outfit so that I looked like a little fairy.

I found exactly the right hole in the hedge to

scrabble through to get into the fields. I ran across

one, the dewy grass soaking the hem of my night-

gown. I stumbled several times, my boots rubbing

my bare feet raw, but I was sure I would soon be

shod in pink satin slippers. I reached the edge of the

field. I fought my way through the second hedge.

There I was, in the circus field – but

where

was the circus?

I opened my eyes wide, staring all

around. Where was the big tent, the wagons, the

horses, Elijah the elephant? Where, oh, where was

Madame Adeline?

Had I come to the wrong field after all? Was

it on through another hedge? Yes, I had simply

miscalculated. But as I wearily started crossing

the empty field, I saw the huge circle of crushed

grass, scatterings of sawdust, the print of wagon

wheels in the earth. Rubbish blew in the wind like

gaudy flowers – all that was left of Tanglefield's

Travelling Circus.

I had found my true mother – and lost

her again.

I trudged all the way back home again. What else

could I do? I didn't know when the circus had

gone. If they'd packed up and travelled all night

after the show, they could now be many miles north,

south, east or west. And I was too small and scared

to run any further. I was freezing cold in spite of

my sack, my nightgown was soaked through and

stained all over with mud where I'd stumbled, and

Gideon's boots seemed intent on paring every inch

of flesh from my feet.

I trailed all the way back to the cottage, and as

I hobbled homewards I did think with satisfaction

that they'd maybe make a fuss of me now. I must

have been missing for hours. I thought of the to-do

when Father returned with Gideon in his arms. I

hoped for just such rejoicing when I limped through

the front door. Mother would cast Gideon aside

and swoop me up into her arms, Nat would clap

his hands, Rosie and Eliza would kiss my pinched

cheeks, and Jem . . .

I gave a genuine little groan as I thought of dear

Jem. How could I have left him without saying a

single word of farewell? He would be heartbroken.

He might be running crazily round the village this

very minute calling for me, striding through the

woods, wading through mud and mire, calling my

name until his voice cracked. I could picture him so

vividly . . .

But I cannot always picture the banal truth.

Jem wasn't out searching for me frantically. Jem

was fast asleep in his bed, not having missed me

for one moment.

None

of the family were aware

that I had run away to join the circus. They

were all still in their beds, snoring. Even baby Eliza

was fast asleep in her cot, though it was past her

feeding time.

I thought I'd changed the world but no one

had noticed. I got into trouble with Mother later

because of the state of my nightgown, but she was

too distracted with Gideon to concentrate on giving

me a paddling.

Gideon did not get properly better. He warmed

up, he ate and drank, he walked around in his

uncomfortable boots, he did his few chores – but

he seemed like a ghost child now. He was more

nervous and timid than ever. If I jumped out at

him and went

'Booo!'

he would cower away from

me and cry, even though he could see it was

only me. He could still laugh, just about, though

I laboured long and hard at this. I pulled faces,

I tickled him, I said silly rude things, I stood on

my hands and waved my legs in the air so he

could see my drawers – and yes, Gideon's nose

might wrinkle, his mouth twitch into a tiny smile.

But he didn't talk any more. He'd always been a

quiet child – well,

any

child living with me would

seem silent by comparison – but now he didn't talk

at

all.

Mother coaxed him, Father badgered him,

the big girls petted him, Nat and Jem tried tricking

him and I certainly plagued him, but he stayed

resolutely silent.

I could offer him some trinket that I knew he

really coveted, perhaps a glass bead as blue as the

sky. I'd put it on the table in front of him and say,

'Do you like this bead I found, Gideon?'

He'd nod.

'Would

you

like it?'

He'd nod more eagerly.

'Well, all you have to do is say, "Please may I have

the bead, Hetty?" and it is yours.'

Gideon's head drooped.

'Come on, Gid, it's

easy.

You can say it, you know

you can. You don't even have to say please. "Can I

have the bead?" That's all you have to say.'

Gideon's head drooped further. I took hold of his

jaw and tried to make his lips mouth the words. No

sound came out, though tears started to roll down

his cheeks.

'Are you

hurting

Gideon, Hetty?' said Mother,

bustling into the room.

'No, no, Mother, I'm simply encouraging him to

speak,' I said.

Mother paused, diverted by my quaint speech.

'You're a caution, Hetty. I've never known a child

like you. I don't know what's to become of you –

or Gideon either.' She suddenly sank to her knees

and opened her arms wide, hugging both of us to

her bosom.

I cuddled up close to Mother. She might not have

the starry glamour of Madame Adeline, she might

be rough with her tongue, she might paddle me hard

for my naughtiness, but she was the only mother I'd

known and I still loved her dearly.

'Don't send us to the hospital, Mother!'

I begged.

She started, as if I'd read her mind. 'I wish I could

keep you, Hetty,' she said, looking straight into my

eyes. 'I can't bear to let you go – and it breaks my

heart to think of little Gideon there, especially not

when . . . when he's not quite himself.'

I wriggled guiltily.

'You will look after your brother when you're at

the hospital, Hetty?' Mother said earnestly. 'He can't

really look after himself. He'll need you to speak up

for him. Will you promise you'll do that, dear?'

'I promise,' I said, though I was shivering so I

could hardly speak.

'It's not as if

all

the children will be strangers,'

said Mother, perhaps trying to convince herself

as well as Gideon and me. 'Saul will be there, and

dear little Martha. They will look out for both

of you.'

I didn't have Mother's faith in my sister and

brother. Besides, the only brother I wanted looking

out for me was my own dear Jem.

I started following him like a little shadow,

tucking my arm in his, huddling close to him at the

table, sitting on his lap. He was so patient with me,

playing endless games of picturing: we were pirates,

we were polar bears, we were soldiers, we were

water babies, we were explorers in Africa – and the

simplest and most favourite game of all, we were

Hetty and Jem grown up and living together in our

own real house, happily ever after.

I was used to dear Jem indulging me, but Gideon

was the family favourite. They treated him now like

a very special frail baby, dandling him on their knees

and ruffling his dark locks. Even Father stopped

trying to turn him into a little man. He hoisted

him onto his huge shoulders and ran around with

him, pretending to be one of his own shire horses.

Gideon squealed in fear and joy, though he still

didn't speak.

But suddenly I seemed to be the pet of the family

too. Father took me out in the fields with him and

held me tight while I rode on the shire's back. The

horse was too big to be a comfortable ride and was

a simple Goliath plodder compared to Madame

Adeline's elegant performing pirate horse – but

even so I kicked my heels and held my arms out,

pretending I was dressed in pink spangles in the

circus ring.

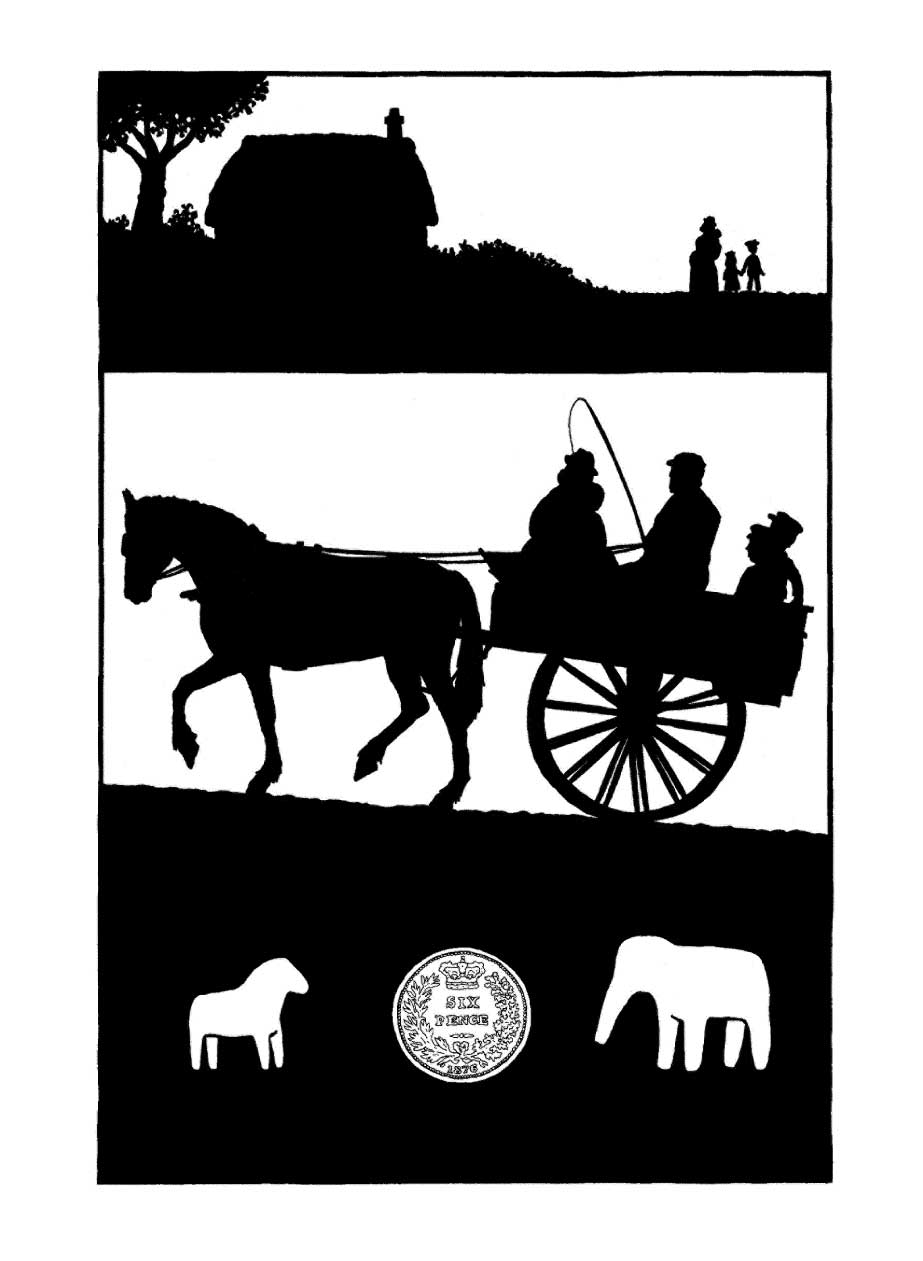

Nat had started whittling simple toys from

pieces of wood. He fashioned me a horse and Gideon

an elephant. To be truthful, the only way we could

distinguish them was by size, but it was kind of my

big brother all the same.

Rosie and Eliza were surprisingly sweet to me

too, letting me play grown-up ladies in their best

dresses, even tying my hair up high and fastening it

with pins. We played we were three big girls together

and they sprayed me with their precious lavender

perfume and told me special big-girl secrets.

Even little Eliza seemed extra fond of me and

smiled and waved her tiny fists in glee whenever I

picked her up.

'You're like a real little mother, Hetty,' said

Mother, sounding truly proud.

I basked in all this praise and attention. For

a child considered ultra-sharp, my wits weren't

working at all. It wasn't till the last night that it

actually dawned on me. Rosie and Eliza sang baby

songs to Gideon and gave us great kisses all over

our cheeks until even my pale brother turned

rosy as an apple. Nat gave us a bear hug. Father

sat us both on his big knees and jiggled us up and

down, playing,

This is the way the ladies ride.

Mother made us each a cup of cocoa brimming with

cream, a rare treat. Just two cups, one for Gideon

and one for me. I looked over at Jem. I knew he

loved cream too.

'Can't Jem have cocoa too, Mother?' I asked.

'No, dear, it's just for you two little ones,' said

Mother. 'Now drink it all up like a good girl before I

get you both ready for bed.'

I went to sit beside Jem, who had been very quiet

all evening. 'Take a sip, Jem,' I whispered.

Jem shook his head quietly. He kept his head

bent but I saw he had tears in his eyes. My stomach

squeezed tight. Why was Jem so sad?

I saw Mother boiling up a great pan of water

on the stove: hot washing water, though it wasn't

bath night. Then at last it dawned on me. She

was going to take Gideon and me to the hospital

tomorrow

!

I'd known for years that I had to go back to the

Foundling Hospital. For the past few months folk

had referred to it openly and often – I had myself.

But it had still seemed distant, long in the future,

not anything to worry about right this minute. But

now suddenly it had sprung upon me. This was

it

–

my last night in the cottage.

The sweet cocoa soured in my mouth. I crept so

near Jem I was practically in his lap. He saw I'd

realized, and put a finger to his lips, nodding at

Gideon. My little brother was smiling as he sipped

his cocoa. Mother pulled off his shirt and said, 'Skin

a rabbit,' and Gideon made a bunny face, twitching

his nose. He was almost his old self again, though

he still wasn't talking. I knew if I cried out that we

were going to the hospital the very next day, Gideon

would be frightened into fits. So I closed my mouth,

pressing my hands over my lips to make certain I

would not talk.

Jem hugged me tight. 'What a dear brave girl you

are, Hetty,' he whispered in my ear.

I didn't want to be brave. I wanted to scream and

make a huge despairing fuss, but I could see that

would spoil everything for Gideon – and for me too.

So I held my tongue and choked down my cocoa,

though I couldn't stop my tears brimming as I gazed

around the little room that had been my home for

the last five years. I could not bear to think I would

never see it again. I could not bear to think I would

not see Mother, Father and my brothers and sisters,

my family. I especially could not bear to think I

would never see my dear Jem again.

The tears rolled down my face and I hid my head

in my hands.

'Look at Hetty, she's tired herself out!'

said Eliza.

'A quick bath in the tub and then you'll be tucked

up in bed, Hetty dear,' said Rosie.

I let my sisters undress me and lift me up into

the soapy water. Mother washed me all over

and rubbed the soapsuds into my hair so hard I

thought the red might run away with the water.

Then I was towelled vigorously, a nightgown

thrust over my head, and I was carried upstairs. I

kept my eyes closed all the time, even when everyone

gave me a goodnight kiss. I was tucked up beside

Gideon, who was already genuinely asleep. I lay

there, waiting.

Then Jem crept upstairs. He got into bed beside

me and put his arms around me. I buried my head

in his chest and wept.

'There, Hetty. There, there, dear Hetty,' he

murmured.

'I don't want to go!' I sobbed. 'I shall run away.

Yes, I shall run away right now.'

'Where will you run to, Hetty?'

'I shall find the circus. I shall live with Madame

Adeline,' I said. 'Perhaps she really is my mother.'

'How will you find the circus? It could be right up

in Scotland or way down in Cornwall. The circus is

gone,

Hetty.'

'I'll still run away,' I said.

'But what will you eat? Where will you live? Who

will look after you?'

'I will eat berries and nuts, and I will sleep curled

up in trees and haystacks and barns.' I paused, trying

to work it out in my head. 'And – and if you will run

away too, Jem, then

you

can look after me.'

'Oh, Hetty. I wish I could. I've tried to plot it out.

I could maybe get farm work far away where they

don't know me – though I'm not really big or strong

enough yet. And you can't work for years and years,

Hetty.'

'You could do the work for me.'

'Yes, but they wouldn't let you tag along too. They

would say you needed to be cared for. They would

seize you and put you in the workhouse, and that

would be much worse than the hospital. So don't

you see, Hetty, we

can't

run away, though I wish we

could with all my heart.'

'Oh, Jem, please please please don't let them take

me away,' I wept, past reasoning.

He held me close and murmured stories in my ear

about my time at the hospital. 'Everyone will like

you – how could they not? – and you will make good

friends there. You will learn lots at school and the

years will go by in a blink, and

then,

when you are

all grown up, I will come and find you, remember?'

'We will truly have our own house?' I snuffled.

'Yes, our own dear house, and we will live there

together. And when I am an old old man with a grey

beard and you are an old old lady, hopefully

not

with

a beard—'

I giggled in spite of everything.

'Then we will scarcely remember we were ever

separated. I promise we will be together and live

happily ever after, just like the fairy tales.'

He told me this over and over until I went to sleep

in a soggy little heap on his chest – and whenever I

woke in the night he whispered it all over again.

Then suddenly Mother was shaking me, easing

me out of bed. I clung frantically to Jem.

'There now, Hetty,' he said. 'Let me dress her,

Mother. You go and get Gideon ready.'

Jem did his best to dress me in my best clothes,

though I did not make it easy for him, keeping my

arms pinned to my sides and curling my feet so they

couldn't be stuffed into my boots.

'Stop being so difficult, Hetty dear,' he said

wearily. 'I will dress too and come with you as far as

I can. Try to be a big brave girl.'