Hidden History: Lost Civilizations, Secret Knowledge, and Ancient Mysteries (11 page)

Read Hidden History: Lost Civilizations, Secret Knowledge, and Ancient Mysteries Online

Authors: Brian Haughton

Tags: #Fringe Science, #Gnostic Dementia, #U.S.A., #Alternative History, #Amazon.com, #Retail, #Archaeology, #History

The throne room in the palace of Knossos.

Some of the most extraordinary

discoveries at Knossos have been the

richly colored frescoes that adorned

the plastered walls, and sometimes

even the floors and ceilings. These

murals show princes, courtly ladies,

fish, flowers, and strange games involving young people leaping over charging bulls. When originally found, these

wall paintings were fragmentary, often

with significant parts missing, and

were subsequently reconstructed and

replaced by Evans and artist Piet de

Jong. Consequently, there has been

much controversy over the accuracy of

the reconstructions, though there

seems to be no doubt that many of the

frescoes are of a religious or ritual

nature.

Between 1700 B.C. and 1450 B.C.,

Minoan civilization was at its peak,

with the city of Knossos and the surrounding settlement having a population of perhaps as many as 100,000.

During this period the Minoan centers

survived two major earthquakes, the

most serious of which probably occurred in the mid-17th century B.C.

(though some researchers date it to as

late as 1450 B.C.), and was caused by a

massive volcanic eruption on the

Cycladic island of Thera (modern

Santorini) 62 miles away from Crete.

The explosion from this eruption was

even greater than the atomic blast at

Hiroshima, and blasted the island of

Thera into three separate parts. Finally, in the mid-15th century B.C., due

to a combination of the accumulative

effects of earthquake damage, periodic invasions from the Greek mainland,

and the collapse of their trade networks, the Minoan civilization began

to decline.

Perhaps its layout is quite complex

-resembling a labyrinth-the Palace

of Minos is thought by some to be the

source of the Theseus and the

Minotaur myth. The main part of the

myth begins when Theseus is in Athens and hears about a blood payment

demanded by King Minos of Crete, for

the murder of his son by the Athenians.

This payment involves sending seven

young Athenian men and seven young

virgin girls to Crete every year, where

they are given to the terrible half-bull,

half-man Minotaur. This beast is kept

shut up in a labyrinth designed by the

famous architect Daedalus. Appalled

at this situation, Theseus volunteers

to be part of the yearly sacrifice and

kill the Minotaur. As he is about to set

off for Crete with the intended victims

on a black-sailed ship, his father King

Aegeus makes Theseus promise that

if he is successful in slaying the

Minotaur, he will, on his return,

change the ship's black sail to white,

as an indication that he is alive and

well. When the group arrives at

Knossos, King Minos' daughter

Ariadne immediately falls in love with

Theseus and agrees to help him kill

the Minotaur. Ariadne gives Theseus

a silk thread, which the hero uses to

help him find his way out of the labyrinth after he has killed the monster.

The couple subsequently set sail for

Athens, but on the way Theseus

deserts Ariadne on the island of

Naxos, where she is rescued by the god

Dionysus. Unfortunately, on his approach to Athens, Theseus forgets his

promise to his father and leaves the

black sail on the ship. King Aegeus,

thinking his son has been killed, leaps

to his death from a cliff.

There is evidence that Knossos's

link with Theseus and the Minotaur

was kept alive long after the Minoans

ceased to exist. This comes mainly in

the form of coinage, and examples include a silver coin from Knossos dated

c. 500 to 413 B.C., which depicts a running Minotaur on one side and a maze

or labyrinth on the reverse. Another

coin shows the head of Ariadne surrounded by a labyrinth. The Minotaur

and labyrinth were also extremely

popular in the Roman period, and numerous mosaics illustrate the Knossos

labyrinth. The most spectacular of

these is probably that from a Roman

villa near Salzburg, in western Austria,

dating to the fifth century A.D. However, some researchers do not believe

the Minotaur originates with the architecture of the Palace at Knossos.

They point out the difference between

a labyrinth, which has only one path

to the center, and a maze, which can

have many. Indeed it is tempting to see

the labyrinth as relating to the maze

as a symbol of the mysteries of life and

death: An abstract concept connected

with religious ritual, where the

Minotaur waiting at the center of the

labyrinth represents something concealed in the heart of all of us.

The story of the 14 youths brought

from Athens to Knossos as a sacrifice

to the Minotaur has always been

thought of as simple myth. But there

is archaeological evidence that perhaps gives some support to this horrific tale. In 1979, in the basement of

the North House within the Knossos

complex, excavators discovered 337

human bones. Analysis of these bones showed that they represented at least

four individuals, all children. Further

examination of the bones revealed the

grisly detail that 79 of them showed

traces of cut marks made by a fine

blade, which bone specialist Loius

Binford interpreted as being made to

remove the flesh. Ruling out the

possibilty that the defleshing of the

bones was part of a burial rite (only

lumps of flesh had been removed, not

every piece), excavator of the site

Peter Warren, Professor of Classical

Archaeology at the University of

Bristol, concluded that the children

were probably ritually sacrificed and

then eaten.

At the four-room sanctuary at

Anemospilia, only 4.3 miles south of

Knossos (first excavated in 1979 by

J. Sakellarikas) another find suggestive of human sacrifice was made.

When investigating the temple's western room, archaeologists found three

skeletons. The first was an 18-year-old

male lying on his right side on an altar in the center of the room, a bronze

dagger at his chest, and his feet tied.

Near to the altar there had once been

a pillar with a channel running around

its base, seemingly intended to catch

blood dripping from a sacrifice. Examination of the dead youth's bones

revealed that he had probably died

from loss of blood. In the southwest

corner of the room, the remains of a

28-year-old female were found

sprawled across the floor, and near the

altar the skeleton of a 5-foot 9-inch tall

male in his late thirties was discovered. This man's hands were raised,

as if trying to protect himself, and his

legs had been broken by falling masonry. A further skeleton, too damaged

to identify, was also found in the building. The temple was destroyed in a fire

around 1600 B.C., which probably resulted from an earthquake. Three of

these individuals had been killed by

the collapsing roof and masonry of the

upper walls, but it seems that the teenager was already dead by this time.

According to the archaeological

evidence, human sacrifice does not

seem to have been widespread on

Minoan Crete. The examples cited

may have been exceptions brought on

by a desperate attempt to appease the

gods in troubled times, probably during violent earthquake activity. A

point worthy of note is that at both the

North House at Knossos and at at the

Anemospilia temple, the sacrifices

were of young adults or children, bringing to mind the seven young men and

seven young women sent by Athens to

satisfy the Minotaur. Perhaps the origins of the Knossos labyrinth legend

were partly in these horrific practices

of human sacrifice, made in unstable

times, when the safety of the entire

community was thought to be at risk.

© Thanassis Vembos.

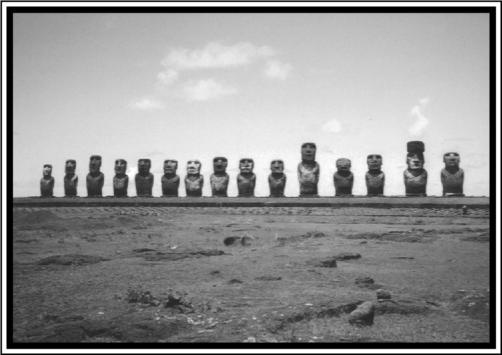

Agroup of moai on their ceremonial platforms.

The most isolated inhabited island

in the world, Easter Island (nowadays

called Rapa Nui, which means Great

Island) is located in the southeast Pacific Ocean, 2,000 miles from the nearest population center. The island is

roughly triangular in shape and composed of volcanic rock. It is most famous for its large number of enigmatic

giant stone statues scattered along the

coast, and perhaps less so for its

undeciphered and mysterious script

known as Rongorongo.

The original inhabitants of Easter

Island called it Te Pito 0 Te Henua

(Navel of the Earth), but who these first

settlers were or where they came from

are much debated subjects. Probably the

most controversial theory about the

peopling of the island was originated

by the Norwegian explorer and archaeologist Thor Heyerdahl. According to

Heyerdahl, Easter Island was partly

settled by a pre-Incan society sailing

from Peru in substantial ocean-going

rafts, with the help of the prevailing

westerly trade winds. In 1947, to prove

it was theoretically possible to make

it across the Pacific in such a vessel,

Heyerdahl built a replica of one of

these balsa wood crafts and named it

the Kon-Tiki, after an Incan Sun God.

Once out in the Pacific, Heyerdahl and

his team sailed for 101 days across

4,349 miles of open sea before crashing into the reef at Raroia atoll, in the Tuamotu Archipelago, east of Tahiti.

In 1951, the documentary Kon-Tiki,

relating the expedition, won an Academy Award. The Kon-Tiki expedition

proved that it was technically possible

for South American peoples to have

crossed the Pacific in a raft and settled

the Polynesian Islands. But there are

one or two problems with Heyerdahl's

experiment. The Kon-Tiki was a type

of vessel copied from rafts in the 16th

century A.D., after the sail had been introduced by the Spanish. So it is not

certain how close his raft was in design

to those in use 800 years before the appearance of the Spanish, when the supposed colonizing expeditions to the

Pacific took place. Furthermore, when

Heyerdahl first attempted to set out on

his journey, the offshore currents were

so strong that the Kon-Tiki needed to

be towed out to sea a distance of 50

miles before it could be sailed.

Heyerdahl also included botanical,

linguistic, and architectural evidence

in his theory of a South American origin for the Easter Islanders, around

A.D. 800. However, archaeological evidence gathered in the years since

Heyerdahl made his daring voyage has

all but disproved his hypothesis, especially as the settlement of the island was already complete by the time

of the proposed trans-Pacific journey.

So where did the first inhabitants of

Easter Island come from? Due to its

extremely isolated position, a voyage

to Easter Island from anywhere would

have taken at least two weeks, over

thousands of miles of open sea. Such a

journey clearly indicates a maritime

people. Polynesian cultures were expert sailors and constructed huge

ocean-going canoes and rafts, navigating by using the position of the stars,

wind direction, and the natural movements of birds and fish. Linguistic evidence points to the settlement of Rapa

Nui by peoples from East Polynesia

between A.D. 300 and A.D. 700, possibly

from the Marquesas Islands or Pitcairn

Island. The latter is the nearest inhabited land, lying 1,199 miles to the west.

This colonization was probably part of

a gradual eastward migration, originating in southeast Asia around 2000 B.C.

A western origin is also indicated by

an Easter Island myth. This myth describes how, around 1,500 years ago, a

Polynesian king named Hotu Matua

(the Great Parent) came to the island

with his wife and family in a double

canoe, by sailing in the direction of the

sunrise from an unspecified Polynesian

island. Just before he died, Hotu Matua

traveled to the western extreme of Easter Island to look for the last time towards his homeland. Recent evidence

from DNA studies has practically ruled

out colonization by South Americans.

Skeletons from burial sites on Easter

Island have been found to contain a genetic marker, called the Polynesian

Motif, proving that the Easter Islanders are descendents of settlers from

eastern Polynesia, not South America.