Hidden History: Lost Civilizations, Secret Knowledge, and Ancient Mysteries (14 page)

Read Hidden History: Lost Civilizations, Secret Knowledge, and Ancient Mysteries Online

Authors: Brian Haughton

Tags: #Fringe Science, #Gnostic Dementia, #U.S.A., #Alternative History, #Amazon.com, #Retail, #Archaeology, #History

Photograph by the author.

Detail of Stonehenge, showing the huge sarsen stones.

It was also in Phase III at Stonehenge that the northeastern entrance

to the enclosure was widened so that

it precisely aligned with the midsummer sunrise and midwinter sunset of

the period. Another feature added to

the Stonehenge landscape during this

phase was the Avenue, a ceremonial

pathway consisting of a parallel pair

of ditches and banks stretching for 1.86

miles from the monument down to the

River Avon.

Around 2300 B.C. the bluestones

were dug up and replaced by enormous

sarsen stones brought from the

Marlborough Downs, 20 miles away.

The sarsens, each around 13.5 feet

high, 6.8 feet wide, and weighing

around 25 tons, were arranged in a 108

foot diameter circle with lintels (horizontal stones) spanning the tops.

Within this circle a horseshoe-shaped

setting of five trilithons (two large

stones set upright to support a third

on their top), of dressed sarsen stone,

was added, its open end facing northeast. The enormous stones, which

made up the central horseshoe arrangement of 10 uprights and five lintels, weighed up to 50 tons each. Later

in this period, between 2280 to 1930

B.C., the bluestones were re-erected

and arranged at least three times, finally forming an inner circle and

horseshoe between the Sarsen Circle

and the Trilithons, mirroring the two

arrangements of sarsen stones. It is thought that more bluestones were

transported from Wales to the site at

this time. Between 2000 and 1600 B.C.

a double ring of pits, known as the

Y and Z holes, were dug outside the

outermost sarsen circle, possibly to

take another setting of stones. However, for whatever reason, no stones

were added and the pits were allowed

to silt up naturally. After 1600 B.C.

there was no further construction at

Stonehenge, and the monument appears to have been abandoned. Nevertheless, the site was still occasionally

visited, as is evidenced by finds of Iron

Age pottery, Roman coins, and the

burial of a decapitated Saxon man

dated to the seventh century A.D.

There has been considerable speculation as to how Stonehenge was built.

An experiment in the 1990s showed

that a team of 200 people, using a

wooden sledge on laid timber rails covered with grease, could have transported all 80 sarsens from the

Marlborough Downs to Stonehenge in

two years, or longer if the work was

seasonal. The experiment illustrated

that the maneuvering of the stones

into position could have been accomplished using timber A-frames to

raise the stones, which could then

have been hauled upright by teams of

people using ropes. The lintels may

have been raised up gradually on timber platforms and levered into position when the primitive scaffolding

reached the top of the upright stones.

A fascinating aspect of the construction of Stonehenge is that the stones

were worked using carpentry techniques. After being hammered to size

using stone balls known as mauls, examples of which have been found at the

site, the stones were fashioned with

mortise and tenon joints so that the

lintels could rest securely on top of the

uprights. The lintels themselves were

joined together using another woodworking method known as the tonguein-groove joint.

Much more interesting than how

Stonehenge was built is why it was

built. Unfortunately, for such an important structure the archaeological

finds from Stonehenge have been relatively meager. This is partly due to the

fact that until the last couple of decades

research at the site had been, on the

whole, poorly performed and insufficiently documented. Skeletons were

lost or seriously damaged, artifacts

misplaced, and excavation notes

destroyed. Despite these losses, the

evidence from surviving burials discovered at or near the site gives a fascinating insight into the lives of Early

Bronze Age peoples in the area.

The main burials at Stonehenge

are all broadly contemporary with

each other, dating from 2400 B.c.-2150

B.C. (the Early Bronze Age period). Examination of a skeleton buried in the

outer ditch of the monument revealed

that the man had been shot at close range by up to six arrows, probably

by two people, one shooting from the

left, the other from the right. Was this

an execution or some form of human

sacrifice? Another astonishing burial

was found in 2002 at Amesbury, 2.8

miles southeast of Stonehenge, and has

become known as either the Amesbury

Archer or the King of Stonehenge. The

rich goods found with this burial indicate a high-status individual, and include five Beaker pots, 16 beautifully

worked flint arrowheads, several boar

tusks, two sandstone wristguards (to

protect the wrists from the bow string

of a bow and arrow), a pair of gold hair

ornaments, three tiny copper knives,

and a flint-knapping kit and metalworking tools. Not only are the gold

objects the oldest ever found in Britain, but this person may have been one

of the earliest metalwokers in the islands. Tests on the skeleton show that

the Archer was a strongly built man

aged between 35 and 45, though he had

an abscess on his jaw and had suffered

an accident, which had torn his left

knee cap off. But the most surprising

element of the burial was yet to come.

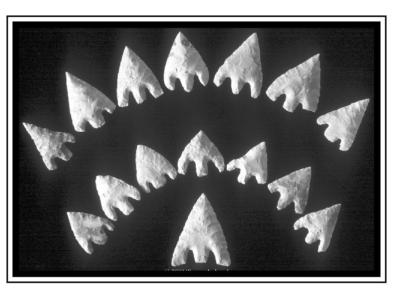

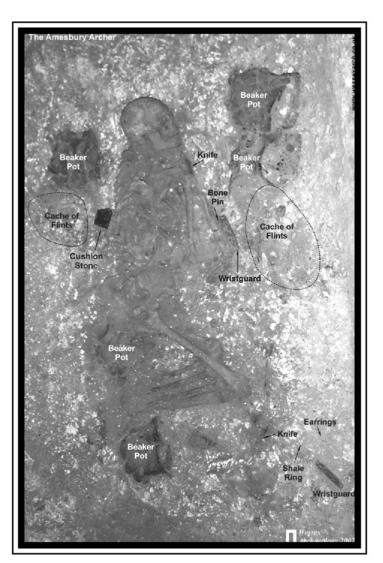

© Wessex Archaeology

Flint arrowheads found with the buried

Archer.

Research using oxygen isotope

analysis on the Archer's tooth enamel

found that he had grown up in the Alps

region, in either Switzerland, Austria,

or Germany. Analysis of the copper

knives showed that they had come

from Spain and France. This is incredible evidence for contact between cultures in Europe 4,200 years ago. Could

the unusually rich burial of the King

of Stonehenge, obviously an important

person of high rank, mean that he

played an important part in the construction of the first stone-built monument on the site? A second male

burial, dating from the same period as

the Archer, was located near to his

grave. This skeleton, which bone

analysis has shown may be the Archer's

son, had been buried with a pair of gold

hair ornaments in the same style as

the Archer's, though for some reason

these had been left inside the man's

jaw. Oxygen isotope analysis revealed

that this man had grown up in the area

around Salisbury Plain, though his late

teens may have been spent in the Midlands or northeast Scotland.

The Boscombe Bowmen are a group

of Early Bronze Age burials, found in

a single grave at Boscombe Down,

close to Stonehenge. Known as bowmen due to the amount of flint arrowheads found in their grave, the burial

consists of seven individuals: three

children, a teenager, and three men,

all apparently related to each other.

Finds from the grave are similar in

character to that of the Amesbury

Archer and include an unusually high

amount of Beaker pottery. Again, it

was the teeth that provided the clue

as to where these people originated.

In this case, the men grew up in Wales

but migrated to southern Britain in

childhood. Given that the Boscombe

Bowmen were roughly contemporary

with the transport and erection of the

Welsh bluestones at Stonehenge, it is

believed by many researchers that they

may have accompanied the stones on

their 186 mile trek to Salisbury Plain.

The burials of the Amesbury Archer

and the Boscombe Bowmen, then,

offer fascinating evidence for some

of the people who were involved in the

task of constructing Stonehenge, but

what purpose did the enigmatic and

unique monument serve?

© Wessex Archaeology

Detail of the Archer burial with

interpretation of the burial goods.

Because Stonehenge is aligned to

the midsummer sunrise/midwinter

sunset, many reseachers (most notably English-born astronomer Gerald

Hawkins) have claimed that a number

of astronomical alignments are present

at the site. However, subsequent analysis of the data assembled to support

Hawkins' theory has shown that many

of the supposed astronomical alignments were arrived at by joining together features from different periods,

as well as natural pits and holes that

were not part of the monument.

The most important thing to remember about Stonehenge is that

although it is a unique structure, it was

not an isolated monument. Stonehenge

grew to be the focal point of a vast prehistoric ceremonial landscape, as can

be seen from the numerous barrow

(burial mound) cemeteries that were

built around the monument. We have

already seen that the Salisbury Plain

landscape had been sacred for thousands of years before the building of

Stonehenge. But in what sense was it

sacred? One theory, put forward by

English archaeologist Mike Parker

Pearson and Ramilisonina, an archaeologist from Madagascar, used modern

anthropological evidence to suggest

that for the Stonehenge people, timber may have been associated with the

living, and the permanence of stone

associated with the ancestors. As there

are two important timber henge sites

close to Stonehenge-Durrington

Walls and Woodhenge-Pearson and

Ramilisonina hypothesized a ritual

route for funeral processions, which

travelled down the River Avon from

wood-built Durrington Walls in the

east at sunrise, and then along the

Avenue up to Stonehenge, the realm

of the ancestors, in the west at sunset.

This would have been a sacred journey

from wood to stone via water, a symbolic passage from life to death. The

paucity of archaeological finds from the

central area inside Stonehenge certainly suggests that only a few people

had access to the monument; not just

anyone could walk inside. Whether

these selected few were priests, or included the Amesbury Archer, it is difficult to tell. But the stone structure as

a metaphor for the ancestors makes a

lot of sense, though it is likely that no

single explanation can ever do justice

to the remarkable people who built

Stonehenge.

© Carlos A. Gomez-Gallo.

Lake Guatavita, allegedly the scene of the Golded Man Ceremony of the

Muisca Tribe.