History of the Second World War (118 page)

Read History of the Second World War Online

Authors: Basil Henry Liddell Hart

Tags: #History, #Military, #General, #Other

It was the Emperor himself who moved to cut the knot. On June 20 he summoned to a conference the six members of the inner Cabinet, the Supreme War Direction Council, and there told them: ‘You will consider the question of ending the war as soon as possible.’ All six members of the Council were in agreement on this score, but while the Prime Minister, the Foreign Minister and the Navy Minister were prepared to make unconditional surrender, the other three — the Army Minister and Army and Navy Chiefs of Staff — argued for continued resistance until some mitigating conditions were obtained. Eventually it was decided that Prince Konoye should be sent on a mission to Moscow to negotiate for peace — and the Emperor privately gave him instructions to secure peace at any price. As a preliminary, the Japanese Foreign Office officially notified Moscow on July 13 that ‘the Emperor is desirous of peace’.

The message reached Stalin just as he was setting off for the Potsdam Conference. He sent a chilly reply that the proposal was not definite enough for him to take action, or agree to receiving the mission. This time, however, he told Churchill of the approach, and it was of this that Churchill told Truman, adding his own tentative suggestion that it might be wise to modify the rigid demand for ‘unconditional surrender’.

A fortnight later the Japanese Government sent a further message to Stalin, trying to make still clearer the purpose of the mission, but received a similar negative reply. Meantime Churchill’s Government had been defeated at the General Election in Britain, so that Attlee and Bevin had replaced Churchill and Eden at Potsdam when, on July 28, Stalin told the Conference of this further approach.

The Americans, however, were already aware of Japan’s desire to end the war, for their Intelligence service had intercepted the cipher messages from the Japanese Foreign Minister to the Japanese Ambassador in Moscow.

But President Truman and most of his chief advisers — particularly Mr Stimson and General Marshall, the U.S. Army’s Chief of Staff — were now as intent on using the atomic bomb to accelerate Japan’s collapse as Stalin was on entering the war against Japan before it ended, in order to gain an advantageous position in the Far East.

There were some who felt more doubts than Churchill records. Among them was Admiral Leahy, Chief of Staff to President Roosevelt and President Truman successively, who recoiled from the idea of employing such a weapon against the civilian population: ‘My own feeling was that, in being the first to use it, we had adopted an ethical standard common to the barbarians of the Dark Age. I was not taught to make war in that fashion, and wars cannot be won by destroying women and children.’ The year before, he had protested to Roosevelt against a proposal to use bacteriological weapons.

The atomic scientists themselves were divided in their views. Dr Vannevar Bush had played a leading part in gaining Roosevelt’s and Stimson’s support for the atomic weapon, while Lord Cherwell (formerly Professor Lindemann), Churchill’s personal adviser on scientific matters, was also a leading advocate of it. It was thus not surprising that when Stimson appointed a Committee under Bush in the spring of 1945 to consider the question of using the weapon against Japan, it strongly recommended that the bomb should be used as soon as possible, and without any advance warning of its nature — for fear that the bomb might prove ‘a dud’, as Stimson later explained.

In contrast, another group of atomic scientists headed by Professor James Franck presented a report to Stimson soon afterwards, in the later part of June, expressing different conclusions: ‘The military advantages and the saving of American lives achieved by the sudden use of atomic bombs against Japan may be outweighed by a wave of horror and repulsion spreading over the rest of the world If the United States were to be the first to release this new means of indiscriminate destruction on mankind, she would sacrifice public support throughout the world, precipitate the race for armaments, and prejudice the possibility of reaching an international agreement on the future control of such weapons. . . . We believe that these considerations make the use of nuclear bombs for an early attack against Japan inadvisable.’

But the scientists who were closest to the statesmen’s ears had a better chance of gaining attention, and their eager arguments prevailed in the decision — aided by the enthusiasm which they had already excited in the statesmen about the atomic bomb, as a quick and easy way of finishing the war. Five possible targets were suggested by the military advisers for the two bombs that had been produced, and of these the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were chosen, after consideration of the list by President Truman and Mr Stimson, as combining military installations with ‘houses and other buildings most susceptible to damage’.

So on August 6 the first atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, destroying most of the city and killing some 80,000 people — a quarter of its inhabitants. Three days later the second bomb was dropped on Nagasaki. The news of the dropping of the Hiroshima bomb reached President Truman as he was returning by sea from the Potsdam Conference. According to those present he exultantly exclaimed: ‘This is the greatest thing in history.’

The effect on the Japanese Government, however, was much less than was imagined on the Western side at the time. It did not shake the three members of the Council of six who had been opposed to surrendering unconditionally, and they still insisted that some assurance about the future must first be obtained, particularly as to the maintenance of the ‘Emperor’s sovereign position’. As for the people of Japan, they did not know until after the war what had happened at Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Russia’s declaration of war on August 8, and immediate drive into Manchuria next day, seems to have been almost as effective in hastening the issue, and the Emperor’s influence still more so. For at a meeting of the inner Cabinet in his presence, on the 9th, he pointed out the hopelessness of the situation so clearly, and declared himself so strongly in favour of immediate peace, that the three opponents of it became more inclined to yield and agreed to holding a Gozenkaigi — a meeting of ‘elder statesmen’, at which the Emperor himself could make the final decision. Meantime the Government announced by radio its willingness to surrender provided that the Emperor’s sovereignty was respected — a point about which the Allies’ Potsdam Declaration of July 26 had been ominously silent. After some discussion President Truman agreed to this proviso, a notable modification of ‘unconditional surrender’.

Even then there was much division of opinion at the Gozenkaigi, on August 14, but the Emperor resolved the issue, saying decisively: ‘If nobody else has any opinion to express, we would express our own. We demand that you will agree to it. We see only one way left for Japan to save herself That is the reason we have made this determination to endure the unendurable and suffer the insufferable.’ Japan’s surrender was then announced by radio.

The use of the atomic bomb was not really needed to produce this result. With nine-tenths of Japan’s shipping sunk or disabled, her air and sea forces crippled, her industries wrecked, and her people’s food supplies shrinking fast, her collapse was already certain — as Churchill said.

The U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey report emphasised this point, while adding: ‘The time lapse between military impotence and political acceptance of the inevitable might have been shorter had the political structure of Japan permitted a more rapid and decisive determination of national policies. Nevertheless, it seems clear that, even without the atomic bombing attacks, air supremacy could have exerted sufficient pressure to bring about unconditional surrender and obviate the need for invasion.’ Admiral King, the U.S. Naval Commander-in-Chief, stated that the naval blockade alone would have ‘starved the Japanese into submission’ — through lack of oil, rice, and other essential materials — ‘had we been willing to wait’.

Admiral Leahy’s judgement is even more emphatic about the needlessness of the atomic bomb: ‘The use of this barbaric weapon at Hiroshima and Nagasaki was of no material assistance in our war against Japan. The Japanese were already defeated and ready to surrender because of the effective sea blockade and the successful bombing with conventional weapons.’

Why, then, was the bomb used? Were there any impelling motives beyond the instinctive desire to cut short the loss of American and British lives at the earliest possible moment? Two reasons have emerged. One is revealed by Churchill himself in the account of his conference with President Truman on July 18, following the news of the successful trial of the atomic bomb, and the thoughts that immediately came into their minds, among these being:

. . . we should not need the Russians. The end of the Japanese war no longer depended upon the pouring in of their armies. . . . We had no need to ask favours of them. A few days later I minuted to Mr Eden: ‘It is quite clear that the United States do not at the present time desire Russian participation in the war against Japan.’*

* Churchill:

The Second World War

, vol. VI, p. 553.

Stalin’s demand at Potsdam to share in the occupation of Japan was very embarrassing, and the U.S. Government were anxious to avoid such a contingency. The atomic bomb might help to solve the problem. The Russians were due to enter the war on August 6 — two days later.

The second reason for its precipitate use, at Hiroshima and Nagasaki, was revealed by Admiral Leahy: ‘the scientists and others wanted to make this test because of the vast sums that had been spent on the project’ — two billion dollars. One of the higher officers concerned in the atomic operation, the codename of which was the ‘Manhattan District Project’, put the point still more clearly:

The bomb simply had to be a success — so much money had been expended on it. Had it failed, how would we have explained the huge expenditure? Think of the public outcry there would have been. . . . As time grew shorter, certain people in Washington tried to persuade General Groves, director of the Manhattan Project, to get out before it was too late, for he knew he would be left holding the bag if we failed. The relief to everyone concerned when the bomb was finished and dropped was enormous.

A generation later, however, it is all too clear that the hasty dropping of the atomic bomb has not been a relief to the rest of mankind.

On September 2, 1945, the representatives of Japan signed the ‘instrument of surrender’ on board the United States’ battleship

Missouri

in Tokyo Bay. The Second World War was thus ended six years and one day after it had been started by Hitler’s attack on Poland — and four months after Germany’s surrender. It was a formal ending, a ceremony to seal the victors’ satisfaction. For the real ending had come on August 14, when the Emperor had announced Japan’s surrender on the terms laid down by the Allies, and fighting had ceased — a week after the dropping of the first atomic bomb. But even that frightful stroke, wiping out the city of Hiroshima to demonstrate the overwhelming power of the new weapon, had done no more than hasten the moment of surrender. This surrender was already sure, and there was no real need to use such a weapon — under whose dark shadow the world has lived ever since.

PART IX – EPILOGUE

CHAPTER 40 - EPILOGUE

KEY FACTORS AND TURNING POINTS

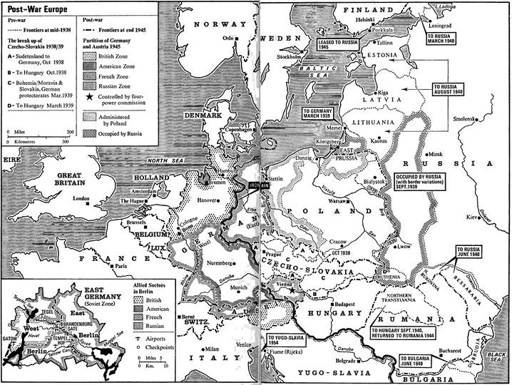

This catastrophic conflict, which ended by opening Russia’s path into the heart of Europe, was aptly called by Mr Churchill ‘the unnecessary war’, In striving to avert it, and curb Hitler, a basic weakness in the policy of Britain and France was their lack of an understanding of strategical factors. Through this they slid into war at the moment most unfavourable to them, and then precipitated an avoidable disaster of far-reaching consequences. Britain survived by what appeared to be a miracle — but really because Hitler made the same mistakes that aggressive dictators have repeatedly made throughout history.

THE VITAL PRE-WAR PHASE

In retrospect it has become clear that the first fatal step, for both sides, was the German re-entry into the Rhineland in 1936. For Hitler, this move carried a two-fold strategic advantage — it provided cover for Germany’s key industrial vital area in the Ruhr, and it provided him with a potential spring-board into France.

Why was this move not checked? Primarily, because France and Britain were anxious to avoid any risk of armed conflict that might develop into war. The reluctance to act was increased because the German re-entry into the Rhineland appeared to be merely an effort to rectify an injustice, even though done in the wrong way. The British, particularly, being politically-minded, tended to regard it more as a political than as a military step — failing to see its strategic implications.

In his 1938 moves Hitler again drew strategic advantage from political factors — the German and Austrian peoples’ desire for union, the strong feeling in Germany about Czech treatment of the Sudeten Germans; and again there was a widespread feeling in the Western countries that there was a measure of justice in Germany’s case on both issues.