History of the Second World War (43 page)

Read History of the Second World War Online

Authors: Basil Henry Liddell Hart

Tags: #History, #Military, #General, #Other

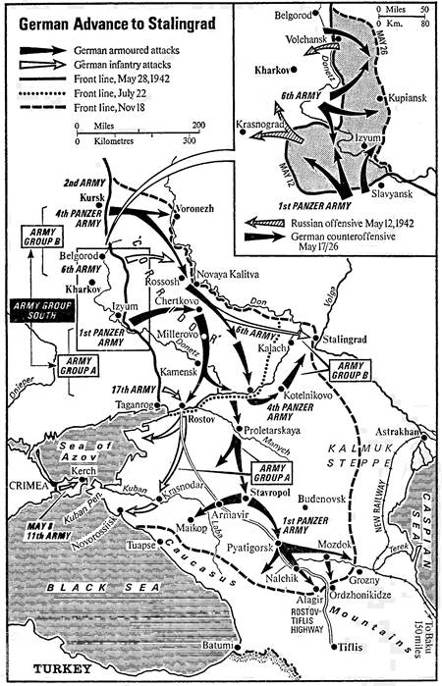

The most effective factor in clearing the path for the German advance was a Russian offensive, towards Kharkov, which began on May 12, striking at Paulus’s 6th Army, which was itself poised to eliminate the Soviet Izyum salient. This was a premature effort, beyond the powers of the Russian Army at this stage in face of the Germans’ defensive skill. Ambitious aims, and excessive anticipations, were suggested by Marshal Timoshenko’s opening ‘Order of the Day’ — which started: ‘I hereby order the troops to begin the decisive offensive.’ The prolongation of this Kharkov offensive played into the Germans’ hands, absorbing too large a part of the Russians’ reserves, and thus laying them open to a deadly riposte. The Russians penetrated the German defences in the Kharkov area and fanned out north-west and south-west. By Hitler’s order the projected offensive against the Izyum salient by Paulus’s 6th Army and Kleist’s 1st Panzer Army was advanced one day and the Russian offensive was brought to an end by Bock’s counteroffensive. Two complete Soviet armies and the elements of two others were cut to pieces, and by the end of May 241,000 Red Army men went into captivity. Few reserves were in hand to meet the Germans when they launched their own main stroke in June.

The German offensive was ‘staggered’ both in siting and timing. It was planned to take place on the whole German front in South Russia, which ran back obliquely from the coast near Taganrog and along the Donetz towards Kharkov and Kursk. It was a battle-front in echelon. The parts farthest back, on the left, were to move first. The more advanced parts, on the right, were to wait for the left wing to come up before trying to advance, but meanwhile helped to exert a flanking leverage that weakened the resistance facing the left.

On the right was the 17th Army, with the 11th Army in the Crimea. Next to the 17th Army, farther back, was the 1st Panzer Army. After July 9 these two armies comprised List’s ‘Army Group A’, destined to invade the Caucasus. On its left was Bock’s ‘Army Group B’, which included the 4th Panzer Army, the 6th Army, the 2nd Army and the 2nd Hungarian Army. The two panzer armies were to deliver the decisive thrusts, both delivered from the Germans’ rear flank against the Russians’ most advanced positions — the 1st striking from the Kharkov sector, and the 4th from the Kursk sector. The ‘infantry’ armies were to follow on and back them up.

As an immediate preliminary to the main offensive, a siege assault was launched against the fortress of Sevastopol on June 7. This was carried out by Manstein’s 11th Army. Although the resistance was tough, the Germans eventually prevailed through superior weight and skill, though it was not until July 4 that the fortress, and with it the whole Crimea, was completely in German hands. The Russians were thus deprived of their chief naval base in the Black Sea. But their fleet was still ‘in being’, although in fact it was to remain passive.

Meanwhile the opening of this move in the Crimea had been followed by another important diversionary offensive closer to the points where the main operation was being mounted. For on June 10 the Germans exploited their Izyum wedge by forcing the passage of the Donetz, and gaining a foothold on the north bank of the river. After expanding this by degrees into a large bridgehead they delivered a powerful armoured stroke northward from it on the 22nd, and in two days reached the junction of Kupiansk some forty miles north of the river. That created an invaluable flanking leverage to assist the easterly thrust of their main offensive, which was launched on the 28th.

On the left wing of the main offensive there was stiff fighting for several days before the Russian reserves ran short and the 4th Panzer Army broke through in the sector between Kursk and Belgorod. After that the advance swept rapidly across the hundred-mile stretch of plain to the Don near Voronezh. This appeared to foreshadow a direct move across the Upper Don and beyond Voronezh, cutting the lateral rail-link from Moscow to Stalingrad and the Caucasus. Actually, the Germans had no such intention. The orders were to halt on reaching the river and turn it into a defensive flank-cover for the south-easterly continuation of the drive. The 2nd Hungarian Army came up to relieve the 4th Panzer Army, which then wheeled south-eastward down the corridor between the Don and the Donetz, followed by the 6th Army — which had the mission of taking Stalingrad.

The whole of the operations on this left wing tended to cloak the menace that was developing on the right wing. For while attention was focused on the thrust from Kursk towards Voronezh, a more dangerous thrust was being delivered by Kleist’s 1st Panzer Army from the Kharkov sector. This profited by the ill-organised position on which the Russian forces stood after the check to their own offensive, as well as by the Kupiansk wedge in the Russians’ flank. After achieving a quick breakthrough, Kleist’s armoured divisions drove eastward down the Don-Donetz corridor to Chertkovo, on the railway from Moscow to Rostov. Then they made a southerly turn, past Millerovo and Kamensk towards the Lower Don at and above Rostov.

The left wing gained a crossing, with little opposition, on July 22 — after an advance of some 250 miles from the starting line. Next day the right wing, arriving on the edge of the Rostov defences, drove a wedge into them. Lying on the west bank of the Don, the city was exposed to such thrusts, and in the rapid flux of the retreat its defences had not been properly organised. The German flanking moves accentuated the confusion, and the city quickly fell into their hands. Its capture cut the pipeline from the Caucasus, leaving the Russian armies dependent for their oil supply on what could be brought in tankers up the Caspian Sea and up the new rail route they had hurriedly laid along the steppes west of it. Russia had also lost another huge slice of her bread supply.

The one important offset to this spectacular sweep was that, though large bodies of Russian troops were overrun, the total captured was not nearly so large as in 1941. The pace had not been quite fast enough. That was due, not so much to the resistance met, as to the earlier loss of so many of the best-trained German tank troops, and the tendency to adopt more cautious methods. The panzer ‘groups’ of 1941 had been reorganised as panzer ‘armies’, with an increased proportion of infantry and artillery; this increase of support tended to cause a decrease of speed.

Although large numbers of Russian troops were momentarily isolated by the German advance, many of them were able to filter back before they could be rounded up. The south-easterly direction of the German sweep made it natural for them to fall back in a north-easterly direction, thus helping the Russian Command to gather them in or near the Stalingrad area, where they became an inherent threat to the flank of the German advance into the Caucasus. That effect had a vital bearing on the next phase of the campaign, when the German armies forked on divergent courses — part for the Caucasus oilfields, and part for the Volga at Stalingrad.

After crossing the Lower Don, Kleist’s 1st Panzer Army wheeled south-eastward into the valley of the Manych River — which is linked by a canal with the Caspian Sea. By blowing up the big dam here, and flooding the valley, the Russians momentarily upset the tanks’ onrush. But after two days’ delay the German forces succeeded in crossing the river and then continued their drive into the Caucasus, fanning out on a wide front. Encouraged by the lack of opposition and the openness of the country, Kleist’s right column drove almost due southward through Armavir to the great oil centre of Maikop, 200 miles south-east of Rostov, which it reached on August 9. On the same day the van of his centre column swept into Pyatigorsk, 150 miles to the east of Maikop, in the foothills of the Caucasus Mountains. His left column took a still more easterly direction, towards Budenovsk. Mobile detachments had been sent racing ahead, and as a result the pace of this early August onrush beyond the Don was terrific.

But the pace slowed down almost as suddenly as it had developed. The prime causes were a shortage of fuel and an abundance of mountains. That dual brake was subsequently reinforced by the distant effect of the struggle for Stalingrad, which drained off a large part of the forces that might have been used to give a decisive impetus to the Caucasus advance.

It was difficult to keep up the flow of fuel supplies required for such a far-ranging sweep, and the difficulty was increased because it had to come by rail through the Rostov bottleneck, and the track had to be converted from the wide Russian to the central European gauge — the Germans could not venture to send supplies by sea while the Russian fleet remained in being. A limited amount was forwarded by air, but the total that came through by rail and air was insufficient to maintain the momentum of the advance.

The mountains were a natural barrier to the attainment of the German objective, but their effect was increased by the increasingly stubborn resistance that was met on reaching this area. Earlier, there had been little difficulty in swerving round the Russian forces which tried to oppose the advance, and the latter had tended to retreat before they were cut off, instead of fighting on stubbornly as in 1941. The change may have been due to a more elastic defensive strategy, though the German Command was convinced, from the interrogation of prisoners, that there was a growing tendency on the part of troops who were by-passed to look for a way of getting back to their homes, especially among those who came from Asiatic Russia. But when the Caucasus was reached the resistance became stiffer. The defending forces here were largely composed of locally recruited troops, who felt that they were protecting their own homes, and were familiar with the kind of mountainous country in which they were fighting. Those factors multiplied the strength of the defence, whereas the nature of the country cramped the attackers by canalising the flood-like advance of their armoured forces.

While the 1st Panzer Army had been carrying out its flanking sweep into the Caucasus, the 17th Army had been following up on foot through the bottleneck of Rostov, whence it turned south towards the Black Sea coast.

After the capture of the Maikop oilfields the Caucasus front was divided afresh, and further objectives allotted. The 1st Panzer Army was given responsibility for the main stretch between the River Laba and the Caspian Sea. Its first objective was to capture the mountain stretch of the great highway running from Rostov to Tiflis; its second objective was Baku, on the Caspian. The 17th Army was responsible for the narrower area from the Laba back to the Kerch Straits. Its first task was to advance southward from Maikop and Krasnodar, across the western end of the Caucasus range, to capture the Black Sea ports of Novorossiisk and Tuapse. Its second objective was to force a passage down the coastal road beyond Tuapse, and thus open the way to Batumi.

While the coastal road south from Tuapse was overhung by high mountains, the first task of the 17th Army looked relatively easy, since it had less than fifty miles to go before reaching the coast, and this western end of the mountain chain sloped away into foothills. But the task did not prove easy. The advance had to cross the Kuban River, which had wide marshy borders near its mouth, and the hills farther east were rugged enough to be difficult obstacles. It was nearly the middle of September before the 17th Army captured Novorossiisk. It never reached Tuapse.

The 1st Panzer Army, on the main line of advance, made better progress by comparison, but at a diminishing pace and with increasing pauses. Fuel shortage was the decisive handicap in the advance to the mountains. The panzer divisions were sometimes at a standstill for several days on end, awaiting fresh supplies. This handicap cost the Germans their best chance — of rushing the passes while surprise lasted, and before the defences were strengthened. When it came to a matter of fighting a way into the mountains the 1st Panzer Army was handicapped because most of the expert mountain troops had been allotted to the 17th Army for its attempt to reach Tuapse and open the coast road to Batumi.

The first serious check occurred on reaching the Terek River — which covered the approaches to the mountain road over to Tiflis, as well as the more exposed Grozny oilfields north of the mountains. The Terek has nothing like the awe-inspiring breadth of the Volga, but its swift current made it an awkward obstacle. Kleist then tried a manoeuvre to the east, downstream, and succeeded in forcing a passage near Mozdok, in the first week of September. But his forces were held up again in the densely wooded hills beyond the Terek. Grozny lay only fifty miles beyond the Mozdok crossing, but all the German efforts failed to bring it within their grasp.

An important factor in this frustration was the way that the Russians switched a force of several hundred bombers to the airfields near Grozny. Their sudden appearance proved the more effective, as a brake on Kleist’s advance, because most of his anti-aircraft units and much of his air force had been withdrawn from him to help the German forces at Stalingrad. Thus the Russian bombers were able to harass Kleist’s army without hindrance, while they also increased its ordeal by setting alight large tracts of the forest through which it was struggling to advance.