History of the Second World War (45 page)

Read History of the Second World War Online

Authors: Basil Henry Liddell Hart

Tags: #History, #Military, #General, #Other

The Germans’ arrival in the built-up area also tended to split up their offensive into a string of localised attacks — which diminished its tidal force. The same limitation fostered a revival of the habit — to which infantry-minded commanders of the old school were prone — of employing tanks in driblets, instead of a flood. Many of the attacks were delivered with a mere twenty or thirty tanks, and although a few of the bigger efforts packed a punch of a hundred tanks, this figure meant only one tank to some 300 men engaged. With so small a proportion it was natural that the anti-tank weapons kept the upper hand. But while these paltry numbers conduced to poor tactics they revealed a growing material deficiency. This became equally marked in the declining scale of air support. The Germans were running short of the two weapons upon which they had mainly depended for their success. As a natural result the burden on the infantry became heavier, and the price of any advance higher.

On the surface, the defenders’ position came to appear increasingly perilous, or even desperate, as the circle contracted and the enemy came closer to the heart of the city. The most critical moment was on October 14, but the German attack was stemmed by General Rodimtsev’s 13th Guards Division. Even after this crisis was overcome the situation remained grave, because the defenders now had their backs so close to the Volga that they had little room left in which to practise shock-absorbing tactics. They could no longer afford to sell ground to gain time. But beneath the surface fundamental factors were working in their favour.

The attackers’ morale was being sapped by increasing losses, a growing sense of frustration, and the coming of winter, while their reserves were so fully absorbed as to leave the overstretched flanks without resiliency. They was thus becoming ripe for the counterstroke which the Russian Command were preparing, and for which it had now accumulated sufficient reserves to make it effective against such overstrained opponents.

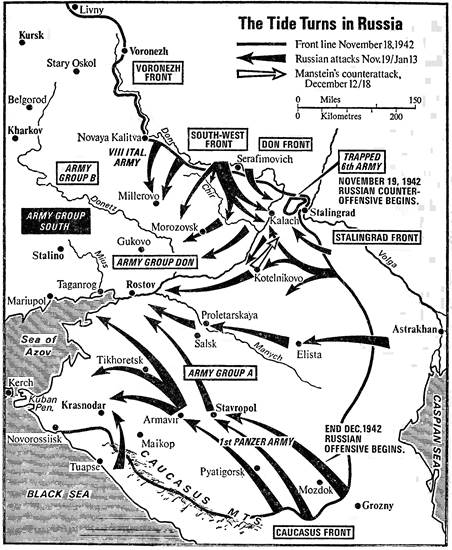

The counterstroke was launched on November 19 and 20, and was well-timed. It started in the interval between the strong first frosts, which harden the ground for rapid movement, and the heavy snows, which clog manoeuvre. It was to catch the Germans at the pitch of exhaustion, just as they were feeling most acutely the natural reaction from the failure of their offensive to bring them victory.

The counterstroke was shrewdly aimed strategically and psychologically — exploiting the indirect approach in a double sense. A pair of pincers, each composed of several prongs, was inserted in the flanks of the Stalingrad attack, so as to isolate the 6th Army and 4th Panzer Army from Army Group B. The pincers were driven in at places where the flank-cover was largely provided by Rumanian troops. The plan was devised by a brilliant triumvirate of the Russian General Staff, Generals Zhukov, Vasilevsky, and Voronov. The principal executants were General Vatutin, commander of the South-western front. General Rokossovsky, commanding the Don front, and General Eremenko, commanding the Stalingrad front.

Here it should be mentioned that the Eastern Front as a whole was divided by the Russians into twelve ‘fronts’ directly under General Headquarters in Moscow. Instead of organising them permanently in larger groups, it now became the Russian practice to send a senior general and staff from General Headquarters to co-ordinate the several ‘fronts’ concerned in any particular series of operations. The ‘fronts’ comprised an average of about four ‘armies’ apiece — which were smaller than in the West — and each of these usually controlled the divisions in it direct without the interposition of army corps headquarters. The armoured and motorised troops were organised in groups of brigades that were called ‘corps’, but were equivalent to large divisions; and these corps were controlled by the ‘front’ commander.

The corps system was re-introduced by the Russians in the summer of 1943, before the new system had a chance to be tested fully. For by cutting out links in the chain of command, and giving the higher commanders a larger number of ‘sub-units’ to handle, operations should be quickened and flexibility of manoeuvre developed. Every additional link in the chain is a

drawback

— in the most literal sense. It tends to cause loss of time both in getting information back to the higher commander, and in getting his orders forward to the real executants. Moreover, it weakens his power of control, both by making his impression of the situation more remote, and by diminishing the force of his personal influence on the executants. Hence the fewer the intermediate headquarters, the more dynamic operations tend to become. On the other hand, an increase in the number of sub-units handled by one headquarters improves the power of manoeuvre by providing more flexibility. A more flexible organisation can achieve greater striking effect because it has more capacity for adjustment to varying circumstances, and for concentration at the decisive point. If a man had only one or two fingers in addition to his thumb he would find it much more difficult to get a properly adjusted grip on any object, or opponent, than he can with four fingers and a thumb. His hand would have less flexibility and less capacity for concentrated pressure. That cramping limitation was seen in the armies of the Western Powers, where most formations and units were divided into only two or three manoeuvrable parts.

North-west of Stalingrad, Russian spearheads thrust down the banks of the Don to Kalach and the railway running back to the Donetz Basin. South-east of Stalingrad the prongs of the left pincers thrust westward to the railway running south to Tikhoretsk and the Black Sea. After cutting this line they pressed on towards Kalach, and by the 23rd the encirclement was completed. It was welded more firmly in the days that followed, enclosing the 6th Army and a corps of the 4th Panzer Army. In those few days of swift movement the Russians had turned the tables strategically while keeping their defensive tactical advantage — that double score which the indirect approach often achieves. For the Germans were now forced to continue attacking — not to break in, but to break out. Their efforts in reverse were as unsuccessful as their earlier efforts to drive forward.

Meanwhile, another powerful Russian force had burst out of the Serafimovich bridgehead, and spread over the country west of the Don bend, in a multi-pronged drive south into the Don-Donetz corridor, to link up on the Chir with the left pincer thrusting on from Kalach. This outer-circle movement was of vital importance to the success of the whole plan, for it upset the enemy’s base of operations and dropped an iron curtain across the more direct routes by which relieving forces might have come to the aid of Paulus.

Thus the German reply, in mid-December, was delivered from the south-west, beyond the Don, up the line from Kotelnikovo to Stalingrad. The troops for it came from a scratch force hastily assembled under Manstein’s 11th Army Headquarters, which had to be withdrawn from Army Group Centre, Manstein’s 11th Army being redesignated ‘Army Group Don’. Its small size hardly justified such an impressive title, and for his attempt to relieve Stalingrad he had to depend on meagre reserves, including the 6th Panzer Division, which had been sent by rail from Brittany in France.

By skilful tactics Manstein made the most of his scanty armour, and succeeded in driving a deep wedge into the Russian covering position. But this hastily improvised advance was checked thirty miles short of the beleaguered Army, and then gradually forced back by Russian pressure on its own flank. With the frustration of this attempt any hope of relieving Paulus passed, for the German Command had no reserves for another attempt. Manstein, however, hung on to his own exposed position as long as he could, and longer than was safe, in order to cover the air lifeline by which a meagre flow of supplies was carried to the doomed army.

Meanwhile, on December 16, the Russians started a fresh outer-circle manoeuvre far to the west. General Golikov, commanding the Voronezh front, launched his left wing across the Middle Don at a number of points on a sixty-mile stretch between Novaya Kalitva and Monastyrshchina — a stretch that was held by the 8th Italian Army. Crossing the hard-frozen Don at first light, tanks and infantry followed up a heavy bombardment which had already put many of the Italians to flight. Snowstorms helped to blind such little opposition as was met, but did not hold up the Russians, who rapidly pushed south towards Millerovo and the Donetz. At the same time Vatutin’s forces struck south-westward from the Chir towards the Donetz. Within a week the converging drives had swept the enemy out of almost the whole of the Don-Donetz corridor. While the defence had been too thin and the rout too rapid for many prisoners to be secured in the first bound, larger numbers of the retreating enemy were overrun and rounded up in the next stage, so that by the end of the second week — which was also the end of the year — the bag reached a total of 60,000.

The sweep threatened the rear of all the German armies on the Lower Don and in the Caucasus. But deepening snow and the stubborn resistance of the German troops at Millerovo and several other communication-centres north of the Donetz averted the danger for the moment.

Nevertheless the menace was so palpable, and its extension so probable, that Hitler was at last brought to realise the inevitability of a disaster greater even than the Stalingrad encirclement if he persisted in his dream of conquering the Caucasus, and compelled the armies there to cling on while their flank was exposed for 600 miles back. So, in January, the order was sent that they were to retreat. The decision was taken just in time for them to escape being cut off. Their successful extrication prolonged the war, but it preceded the actual surrender of the Stalingrad armies in making clear to the world that the German tide was on the ebb.

The course of the Russian counteroffensive had been marked by the skill with which General Zhukov chose his thrust-points — as much on psychological as on topographical grounds. He hit the moral soft-spots in the enemy’s dispositions. Moreover, he had shown his ability to develop an alternative kind of threat once his striking forces lost the immediate local tide, and the chance it carried of producing a general collapse. As a concentrated thrust has a diminishing effect in straining a defender’s resisting power, he had renewed the initial effect by developing a widely distributed series of thrusts, aimed to extend the strain. That usually tends to be the more profitable, and less self-exhausting, form of strategy when a counteroffensive grows into an offensive and no longer enjoys its initial recoil-spring impetus.

Beneath all the other factors, material and moral, that governed the course of events lay the basic condition of the ratio between space and force. Space was so

wide

on the Eastern front that an attacker could always find room for outflanking manoeuvre if he did not concentrate upon too obvious an objective — such as Moscow in 1941, and Stalingrad in 1942. Thus the Germans had been able to gain their offensive successes without a superiority in numbers, so long as they kept a qualitative superiority. The fact that space was so

deep

on the Eastern front was, however, a saving factor for the Russians during the time they were unable to match the Germans in mechanised power and manoeuvrability.

But the Germans had lost that technical and tactical advantage, while they had also used up much of their manpower. With that shrinkage of their forces the wide spaces of Russia had turned to their disadvantage, endangering their capacity to hold such an extended front. The question now became whether they could recover their balance by contracting their front, or whether they had expended so much of their strength as to leave them no chance.

CHAPTER 19 - ROMMEL’S HIGH TIDE

The campaign of 1942 in Africa saw even more violent and far-reaching reversals of fortune than had taken place in 1941. It started with the rival armies facing one another on the Western border of Cyrenaica — exactly where they had stood nine months before. But when the new year was three weeks old Rommel launched one more of his strategic counterstrokes, which went more than 250 miles deep, and swept the British two-thirds of the way back to the Egyptian frontier before they rallied. There the front crystallised, on the Gazala line.

Near the end of May, Rommel struck again, forestalling a British offensive — just as his own had been forestalled in November. This time, after another whirling battle of breath-catching changes, the British were driven to retreat — so fast and so far that they did not rally until they reached the Alamein line, the final gateway into the Nile Delta. This time Rommel’s exploiting thrust had gone more than 300 miles deep in a week. But its momentum, and his strength, were by then nearing exhaustion. His efforts to push on to Alexandria and Cairo were checked, and he was desperately close to defeat before the battle ended in mutual exhaustion.

At the end of August, after being reinforced, he made one more effort for victory. But the British had been more heavily reinforced and — under a new team of commanders, headed by General Sir Harold Alexander and General Sir Bernard Montgomery — his thrust was parried, and he was forced to yield most of his slight initial gains.