History of the Second World War (50 page)

Read History of the Second World War Online

Authors: Basil Henry Liddell Hart

Tags: #History, #Military, #General, #Other

It was also natural that the prevailing disappointment at the end of the battle in July should have renewed the impression of bad leadership left by the disaster in June, and developed an impulsive feeling that drastic changes were needed in the higher command. As usual, criticism was focused on the top of the ladder, rather than where the slips and bungles had occurred, lower down. There was better justification in the need to restore the confidence of the troops, which had been shaken afresh by the failure of Auchinleck’s counteroffensive. In such conditions, a change of command is the easiest way to provide a tonic and may be essential as a stimulant — however unjust to the commander who is replaced.

Churchill decided to fly out to Egypt, to size up the situation, and arrived in Cairo on August 4 — the fateful anniversary of Britain’s entry into World War I. Although Auchinleck had ‘stemmed the adverse tide’, as Churchill recognised and said, it was not so apparent that the tide had actually turned, as can be seen in retrospect. Rommel still stood barely sixty miles from Alexandria and the Nile Delta — disturbingly close. Churchill was already thinking of making a change in the command, and his inclination turned into decision after finding that Auchinleck strongly resisted his pressure for an early renewal of the offensive, and insisted that it must be deferred until September in order to give the new reinforcements time to become acclimatised and have some training in desert conditions.

His decision was also influenced and fortified by discussion with Field-Marshal Smuts, the South African Prime Minister, who had flown to Egypt at his request. Churchill’s first idea was to offer the command to the very able Chief of the Imperial General Staff, General Sir Alan Brooke — but Brooke, from motives of delicacy as well as of policy, did not wish to leave the War Office and take Auchinleck’s place. So after further discussion, Churchill telegraphed to the other members of the War Cabinet in London that he proposed to appoint Alexander as Commander-in-Chief, and to give the command of the Eighth Army to Gott — a surprising choice in the light of this gallant soldier’s fumbling performance as a corps commander in the recent battles. But Gott was killed in an air crash next day, on his way to Cairo. Montgomery was then, fortunately, brought out from England to fill the vacancy. Two fresh corps commanders were also flown out — Lieutenant-General Sir Oliver Leese to take over the 30th Corps and Lieutenant-General Brian Horrocks to fill the vacancy in the 13th.

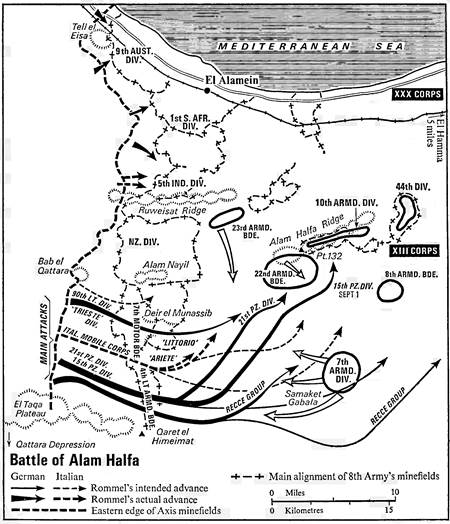

But an ironical result of these changes was that the resumption of the British offensive was put off to a much later date than Auchinleck had proposed. For the impatient Prime Minister had to give way to Montgomery’s firm determination to wait until preparations and training were completed. This entailed leaving the initiative to Rommel, and allowing him another chance to bid for victory in what was to be called the ‘Battle of Alam Haifa’ — but in effect only gave him ‘enough rope to hang himself’.

During August only two fresh formations arrived to reinforce Rommel — a German parachute brigade and an Italian parachute division. Both came ‘dismounted’, for employment as infantry. But the losses in the divisions already engaged were made up to a considerable extent by drafts and fresh supplies of equipment — although much more arrived for the Italian divisions than for the German. By the eve of the attack, which Rommel was planning to deliver at the end of August, he had about 200 gun-armed tanks in the two panzer divisions, and 240 in the two Italian armoured divisions. While the Italian tanks were still of the old model, now more obsolete than ever, the German Panzer IIIs included seventy-four with the long 50-mm. gun, and twenty-seven of the Panzer IVs mounted the new long 75-mm. gun. That was an important qualitative gain.

But the British tank strength at the front had been brought up to a total of over 700 (of which some 160 were Grants). In the event, only some five hundred were used in the armoured battle — which this time was brief.

The fortified front was still held by the same four infantry divisions as in July, with strength rebuilt, and the 7th (Light) Armoured Division remained, while the 1st Armoured Division went back to refit and was replaced by the 10th (commanded by Major-General A. H. Gatehouse) — which comprised two armoured brigades, the 22nd and the newly arrived 8th, while the re-equipped 23rd was also put under its command after the battle started. A newly arrived infantry division was also brought to the front to hold the rearward position on the Alam Haifa Ridge.

No radical change was made in the defence that had been designed by Dorman-Smith and approved by Auchinleck while he was still in command. After the battle was won, it was widely reported that the plan was completely recast following the change of command. So it should be emphasised that Alexander, in his Despatch, stated the facts with an honesty shattering to such stories and claims. He said that when he took over the command from Auchinleck:

The plan was to hold as strongly as possible the area between the sea and Ruweisat ridge and to threaten from the flank any enemy advance south of the ridge from a strongly defended prepared position on the Alam el Halfa ridge. General Montgomery, now in command of Eighth Army, accepted this plan in principle, to which I agreed, and hoped that if the enemy should give us enough time he would be able to improve our positions by strengthening the left or southern flank.*

* Alexander:

Despatch,

p. 841.

The Alam Haifa position was reinforced before Rommel attacked, but its defence was not seriously tested — for the issue of the battle was decided by the well-judged positioning of the armour, and its very effective defensive action.

The northern and central sectors of the front were so strongly fortified that the southern stretch of fifteen miles, between the New Zealanders’ ‘box’ on the Alam Nayil Ridge and the Qattara Depression, was the only part of the front where a quick penetration could possibly succeed. Thus in trying to achieve a breakthrough Rommel was bound to take that line of advance. That was obvious — and was what the defence plan evolved under Auchinleck had been designed to produce.

Surprise in aim-point was thus impossible, so Rommel had to depend on achieving surprise in time and speed. He hoped that if he broke through the southern sector quickly, and got astride the Eighth Army’s communications, it would be thrown off balance and its defence disjointed. His plan was to capture the mined belt by a night attack, after which the Afrika Korps with part of the Italian Mobile Corps would drive on eastward for about thirty miles before daylight, and then wheel north-east to the coast towards the Eighth Army’s supply area. This threat, he hoped, would lure the British armour into a chase, giving him the chance to trap and destroy it. Meanwhile the 90th Light Division and the rest of the Italian Mobile Corps were to form a protective corridor strong enough to resist counterattacks from the north until he had won the armoured battle, in the British rear. In his own account, he says that he ‘placed particular reliance on the slow reaction of the British command, for experience had shown us that it always took them some time to reach decisions and put them into effect’.

But when the attack was launched, on the night of August 30, it was found that the mined belt was much deeper than expected. At daylight, Rommel’s spearheads were only eight miles beyond it, and the bulk of the Afrika Korps was not able to start on its eastward drive until nearly 10 a.m. By that time its mass of vehicles was being heavily bombed by the British air force. The corps commander, General Walter Nehring, was wounded at an early stage, and during the rest of the battle, the Afrika Korps was commanded by its Chief of Staff, Lieutenant-General Fritz Bayerlein.

When it was clear that any surprise-effect had vanished, and that the rate of advance was badly behind time, Rommel thought of breaking off the attack. But after discussion with Bayerlein, and following his own natural inclination, he decided to continue it — although with modified aims and more limited objectives. As it was obvious that the British armour had been allowed time to take up its battle-positions, and could thus threaten the flank of a deeply extended drive, he felt bound to make ‘an earlier turn north than we had intended’. He therefore ordered the Afrika Korps to make an immediate wheel, so that it headed for Point 132, the dominant feature of the Alam Haifa Ridge. This change of direction brought it towards the area where the 22nd Armoured Brigade was posted — and also towards an area of soft sand, cramping to manoeuvre. The line of thrust originally planned had been well clear of this ‘sticky’ area.

The 8th Armoured Brigade’s battle positions were some ten miles distant, to the south-east, from the 22nd — more directly placed to check a bypassing move, instead of trusting to the indirect check and threat of a flanking position. In accepting the risk of posting the brigades so far apart, Montgomery could rely on the fact that each of them was almost as strong in armour as the whole Afrika Korps, and should therefore be capable of holding out until the other brigade arrived to support it.

The 8th, however, did not reach its assigned position until 4.30 a.m. — it was fortunate that the enemy had been so much delayed, for under Rommel’s original plan the Afrika Korps had been directed on that same area and intended to arrive there before dawn. A collision in the dark, or assault in the morning, before the 8th was firmly in position, might have produced an awkward situation, especially for troops who were in action for the first time.

As a result of Rommel having to wheel north earlier than he had intended, the attack fell directly on the 22nd Armoured Brigade, and on that alone — but not until late in the day. For continued air attacks, and the delayed arrival of fuel and ammunition convoys, had such a retarding effect on the advance that the Afrika Korps did not begin even the shortened northward wheel until the afternoon. On approaching Alam Haifa, and the battle positions of the 22nd Armoured Brigade, the panzer columns came under a storm of fire from the well-sited tanks and then from the supporting artillery of this all-arms brigade group — which was ably handled by its new and young commander, ‘Pip’ Roberts. Repeated advances and attempted local flank moves were checked — until nightfall closed down the fight, bringing well-earned respite to the defenders and spreading depression among the attackers.

The abortiveness of the attack was due, however, not only to these actual repulses. For fuel was so short in the Afrika Korps that in mid-afternoon Rommel had cancelled his orders for an all-out effort to capture Point 132.

Even when morning came on September 1, there was still such a shortage of fuel that Rommel was forced to give up the idea of carrying out any large operation that day. The most that he could attempt was a local and limited attack with one division, the 15th Panzer, to seize the Alam Haifa Ridge. The Afrika Korps was now in a very awkward predicament, and it suffered growing loss as the battering it had endured during the night from British bombers and the artillery of Horrocks’s 13th Corps continued throughout the day. The diminished attacks of the German armour were successively checked, by a reinforced defence — for early that same morning Montgomery, now sure that the enemy was not driving on east towards his rear, had ordered the two other armoured brigades to concentrate alongside Roberts’s.

By the afternoon Montgomery ‘ordered planning to begin for a counter-stroke which would give us the initiative’. The idea was, by a wheeling attack southward from the New Zealanders’ position, to cork the neck of the bottle into which the Germans had pushed. He also made arrangements to bring up the headquarters of the 10th Corps ‘to command a pursuit force’, that was ‘to be prepared to push through to Daba with all reserves available’.

The Panzerarmee now had only one day’s fuel issue left in hand — a quantity sufficient only for about sixty miles movement for its units. So, after a second night of almost continuous bombing, Rommel had decided to break off the offensive, and make a gradual withdrawal.

During the day, the Germans facing Alam Haifa were seen to be thinning out, and starting to move westward. But requests for permission to follow them up were refused — for it was Montgomery’s policy to avoid the risk of his armour being lured into Rommel’s traps, as had happened so often before. At the same time Montgomery gave orders that the southward attack by New Zealanders, reinforced by other troops, was to start on the next night but one, September 3/4.

But on September 3 Rommel’s forces began a general withdrawal, and were only followed up by patrols. The ‘bottling’ attack was launched that night, against the enemy’s rear flank, which was being guarded by the 90th Light and Trieste Divisions. The attack became badly mixed up, suffering heavy loss, and was broken off.

On the next two days, September 4 and 5, the Afrika Korps continued its gradual withdrawal, and no further effort was made to cut it off, while it was only followed up in a very cautious way, by small advanced parties. On the 6th the Germans halted on a line of high ground six miles east of their original front, and were obviously intending to make a strong stand there. Next day, Montgomery decided, with Alexander’s approval, to break off the battle. So Rommel was left in possession of this limited gain of ground in the south. It was small consolation for his losses, and the decisive frustration of his original aims.