History of the Second World War (93 page)

Read History of the Second World War Online

Authors: Basil Henry Liddell Hart

Tags: #History, #Military, #General, #Other

CHAPTER 31 - THE LIBERATION OF FRANCE

Before its launching, the invasion of Normandy looked a most hazardous venture. The Allied troops had to disembark on a coast that the enemy had occupied during four years, with ample time to fortify it, cover it with obstacles and sow it with mines. For the defence, the Germans had fifty-eight divisions in the West, and ten of these were panzer divisions that might swiftly deliver an armoured counterstroke.

The Allies’ power to bring into action the large forces now assembled in England was limited by the fact that they had to cross the sea, and by the number of landing craft available. They could disembark only six divisions in the first seaborne lift, together with three airborne, and a week would pass before they could double the number ashore.

So there was cause to feel anxious about the chances of storming what Hitler called the ‘Atlantic Wall’ — an awesome name — and about the risks of being thrown back in the sea.

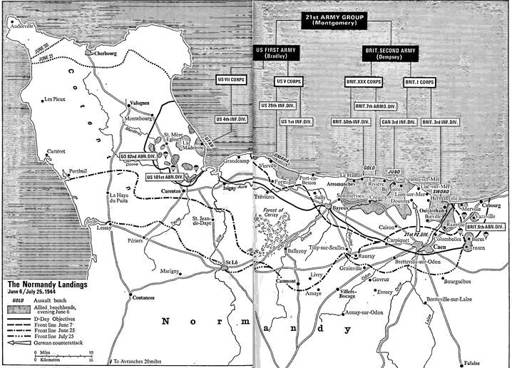

Yet, in the event, the first footholds were soon expanded into a large bridgehead, eighty miles wide. The enemy never managed to deliver any dangerous counterstroke before the Allied forces broke out from the bridgehead. The break-out was made in the way and at the place that Field-Marshal Montgomery had originally planned. The whole German position in France then quickly collapsed.

Looking back, the course of the invasion appears wonderfully easy and sure. But appearances are deceptive.

It was an operation that eventually ‘went according to plan’, but not according to timetable. At the outset the margin between success and failure was narrow. The ultimate triumph has obscured the fact that the Allies were in great danger at the outset, and had a very narrow shave.

The common idea that the invasion had a smooth and sure run was rostered by Montgomery’s subsequent emphasis that ‘the battle was fought exactly as planned before the invasion’, and the fact that the Allied armies reached the Seine within ninety days — the line shown on the forecast map, produced in April, as the line to be gained by ‘D + 90’.

It was ‘Monty’s way’ to talk as if any operation that he had conducted had always proceeded exactly as he intended, with the certainty and precision of a machine — or of divine providence. That characteristic has often obscured his adaptability to circumstances, and thus, ironically, deprived him of the credit due to him for his combination of flexibility with determination in generalship.

In the original plan, Caen was to be captured the first day of the landing, June 6. The start was good and the coastal defences were overcome by 9 a.m. But Montgomery’s account has covered up the fact that the advance inland to Caen did not start until the afternoon. That was due partly to a paralysing traffic jam on the beaches but also to the excessive caution of the commanders on the spot — at a time when there was hardly anything to stop them. When they eventually pushed on towards Caen, the keypoint of the invasion area, a panzer division — the only one in the whole invasion area of Normandy — arrived on the scene and produced a check. A second panzer division came up next day. More than a month passed before Caen was at last secured and cleared, after much heavy fighting.

Montgomery’s original intention, also, was that on the British right wing an armoured force would make an immediate drive inland to Villers-Bocage, twenty miles from the coast, and so cut the roads running west and south-west from Caen. But this is not mentioned in his story. The fact is that this push was very slow to get going, although opposition west of Caen was negligible once the coast defences had been penetrated. Prisoners subsequently revealed that until the third day a ten mile stretch of front was covered by one solitary German mobile unit, a reconnaissance battalion. A third panzer division then began to arrive on the scene, and was put in here. Although the British managed to push into Villers-Bocage on the 13th, they were pushed out again. Then a fourth panzer division reinforced the block. Two months passed before Villers-Bocage was finally captured.

The original idea, too, was that the whole of the Cotentin peninsula, along with the port of Cherbourg, would be captured within two weeks, and that the break-out would then be made, by ‘D + 20’, on this western flank. But the advance inland from the American landing points, on this flank, also proved much slower than expected, although the larger part of the German forces, and later-arriving reinforcements, were absorbed in checking the British advance on the eastern flank near Caen — as indeed Montgomery had calculated.

While the break-out ultimately came on the western flank, as Montgomery had planned, it did not come until the end of July — ‘D + 56’.

It had been clear beforehand that, if the Allies could gain a bridgehead sufficiently wide and deep to build up their strength on the far side of the Channel, their total resources were so much greater than the enemy’s that the odds were heavily on a break-out sooner or later. No dam was likely to be strong enough to hold the invading flood in check permanently if the Allies gained enough space to pile up their massed power.

As things turned out the prolongation of the ‘Battle of the Bridgehead’ worked out to their advantage. It was the proverbial ‘blessing in disguise’. For the bulk of the German forces in the West was drawn there, while arriving bit by bit owing to divided views in their High Command and constant hindrance from the vast Allied force that dominated the sky. The panzer divisions, arriving first and used to plug gaps, were ground down first — thus depriving the enemy of the mobile arm he needed when it came to fighting in the open country. The very toughness of the resistance that so much delayed the Allies’ break-out ensured them a clear path through France once they broke out.

The Allies would have had no chance of ever getting established ashore but for their complete supremacy in the air. They owed much to the support from naval gunfire, but the decisive factor was the paralysing effect of the Allied air forces, directed by Air Chief Marshal Tedder, Eisenhower’s deputy as Supreme Commander. By smashing most of the bridges over the Seine on the east and over the Loire on the south, they turned the Normandy battle-zone into a strategical isolation-zone. The German reserves had to make long detours, and were so constantly harried on the march, that they suffered endless delays and only arrived in driblets.

But almost as much was owed to a conflict of ideas on the German side — between Hitler and his generals, and among the generals themselves.

Initially, the Germans’ main handicap was that they had 3,000 miles of coastline to cover — from Holland round the shores of France to the Italian mountain frontier. Of their fifty-eight divisions, half were of a static type, and anchored to sectors of that long coastline. But the other half were field divisions, and of these the ten panzer divisions were highly mobile. That provided the enemy with the possibility of concentrating an overwhelming superiority to throw the invaders back into the sea before they became established and grew too strong for eviction.

On D-Day the one panzer division that was in Normandy, and near the stretch where the Allies landed, succeeded in frustrating Montgomery’s hope of capturing the key-point of Caen that day. Part of it actually pierced the British front and drove through to the beach, but the thrust was too small to have a wide effect.

If even the three panzer divisions, out of ten, that were on the scene by the fourth day had been at hand and able to intervene on D-Day the Allied footholds could have been dislodged before they were joined up and consolidated. But any such strong and prompt counterstroke was frustrated by discord in the German Command, both about the probable site of the invasion and the method of meeting it.

Before the event, Hitler’s intuition proved better than his generals’ calculation in gauging where the Allies would land. After the landing, however, his continual interference and rigid control deprived them of the chance of retrieving the situation, and eventually led to disaster.

Field-Marshal von Rundstedt, the Commander-in-Chief in the West, thought the invasion would come across the narrower part of the Channel, between Calais and Dieppe. His view was based on a conviction that this course was the more correct strategy for the Allies to follow. But it was fostered by a lack of information. Nothing important leaked out from the tight-lipped island where the invasion armies were assembling.

Rundstedt’s Chief of Staff, General Blumentritt, later related in interrogation how badly baffled was the German Intelligence:

Very little reliable news came out of England. [Intelligence] gave us reports of where, broadly, the British and American forces were assembling in Southern England — there were a small number of German agents in England, who reported by wireless transmitting sets what they observed.* But they found out very little beyond that . . . nothing we learnt gave us a definite clue where the invasion was actually coming.†

* There is virtually no evidence to support this — B.H.L.H.

† Liddell Hart:

The Other Side of the Hill,

pp. 391-2.

Hitler, however, had a ‘hunch’ about Normandy. From March onward he sent his generals repeated warnings about the possibility of a landing between Caen and Cherbourg. How did he arrive at that conclusion, which proved correct? General Warlimont, who was on his staff, said that it was inspired by the general lay-out of the troops in England — with the Americans in the south-west — along with his belief that the Allies would seek to capture a big port as early as possible, and that Cherbourg was the most likely for their purpose. His conclusion was strengthened by observers’ reports of a big invasion exercise in Devon where the troops disembarked on a stretch of flat and open coastline similar to the intended area in Normandy.

Rommel, who was in executive charge of the forces on the Channel coast, came round to the same view as Hitler. In the last few months he made feverish efforts to hasten the construction of under-water obstacles, bomb-proof bunkers, and minefields, and by June they were much denser than they had been in the spring. But, fortunately for the Allies, he had neither the time nor the resources to develop the defences in Normandy to the state he desired, or even to the state of those east of the Seine.

Rommel also found himself in disagreement with Rundstedt over the method of meeting an invasion. Rundstedt relied on a plan of delivering a powerful counteroffensive to crush the Allies after they had landed. Rommel considered that this would be too late, in face of the Allies’ domination of the air and their capacity to delay the German reserves in concentrating for such a counteroffensive.

He felt that the best chance lay in defeating the invaders on the coast, before they were properly ashore. Rommel’s staff said that ‘he was deeply influenced by the memory of how in Africa he had been nailed down for days on end by an air force not nearly so strong as that he now had to face’.

The actual plan became a compromise between these different ideas — and ‘fell between two stools’. Worse still, Hitler insisted on trying to control the battle from remote Berchtesgaden, and kept a tight hand on the use of the reserves.

There was only one panzer division at Rommel’s disposal in Normandy, and he had brought this close up behind Caen. So it was able to check the British there on D-Day. He had begged in vain for a second one to place near St Lo — where it would have been close to the beaches where the Americans landed.

On D-Day precious hours were wasted in argument on the German side. The nearest available part of the general reserve was the 1st S.S. Panzer Corps, which lay north-west of Paris, but Rundstedt could not move it without permission from Hitler’s headquarters. Blumentritt stated:

As early as 4 a.m. I telephoned them on behalf of Field-Marshal von Rundstedt and asked for the release of this Corps — to strengthen Rommel’s punch. But Jodl, speaking for Hitler, refused to do so. He doubted whether the landings in Normandy were more than a feint, and was sure that another landing was coming east of the Seine. The battle of argument went on all day until 4 p.m., when this Corps was at last released for our use.*

*

Liddell Hart:

The Other Side of the Hill,

p. 405.

Two other startling facts about the opening day are that Hitler himself did not hear of the landing until very late in the morning, and that Rommel was off the scene. But for these factors, action might have been more prompt and more forceful.

Hitler, like Mr Churchill, had a habit of staying up until long after midnight — a habit very exhausting to his staff, who could not sleep late but were often in a sleepy state when they dealt with affairs in the morning. Jodl, reluctant to disturb Hitler’s late morning sleep, took it upon himself to resist Rundstedt’s appeal for the release of the reserves.

They might have been released earlier if Rommel had not been absent from Normandy. For, unlike Rundstedt, he often telephoned Hitler direct and still had more influence with him than any other general. But Rommel had left his headquarters the day before on a trip to Germany. As the high wind and rough sea seemed to make invasion unlikely for the moment he had decided to combine a visit to Hitler, to urge the need of more panzer divisions in Normandy, with a visit to his home near Ulm for his wife’s birthday. Early next morning, before he could drive on to see Hitler, a telephone call told him that the invasion had begun. He did not get back to his headquarters until the evening — by which time the invaders were well established ashore.