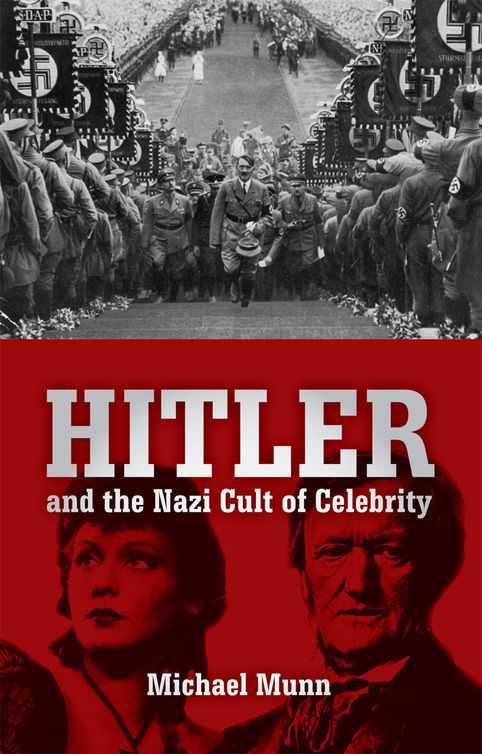

Hitler and the Nazi Cult of Celebrity

Read Hitler and the Nazi Cult of Celebrity Online

Authors: Michael Munn

MICHAEL MUNN

Chapter 1. Celebrity, Sex and Death

Chapter 3. Impurity of the Blood

Chapter 7. The Holy Family of the Third Reich

Chapter 8. Merchandising Adolf

Chapter 9. Seven Chambers of Culture

Chapter 12. The Will to Triumph

Chapter 13. Leading Ladies of the Third Reich

Chapter 15. The Depths of Hell

Chapter 16. The Führer Versus the Phooey

Chapter 17. A Reflection of Hitler

T

he Nazis had a cult for almost everything. Not every cult was necessarily given a name or was recognised as Nazi policy, but Joseph Goebbels acknowledged that cults were a fundamental element of Nazism. To celebrate the occasion of the end of a heroic life, they had a cult of death. To maintain mystical and symbolic rituals Hitler felt were essential to Germanic culture and history, there was the cult of the blood banner. Hitler, identifying with the Roman emperor Nero, indulged in a cult of fire. One might even suggest a cult of suicide existed although most others were

unwilling

to be a part of it. And to elevate Hitler to the

Führer

, the party embraced the cult of personality.

Hitler was a product of his own making who created his own cult of personality using the forms of media available to him at the time, which, combined with judiciously formulated propaganda, produced and promoted a carefully honed heroic and almost divine public image. By the beginning of the twentieth century the divine right of kings who held their office by the will of God was quickly giving way to other forms of government, some democratic and some dictatorial, and from the latter rose the cult of

personality

, which took advantage of all the technical accomplishments of the modern world such as photography, sound recording, film and mass publications. Hitler was, alongside Stalin, one of the first to dominate the political stage through technology. But Hitler went further than Stalin in communicating his image because unlike Stalin, Hitler didn’t set out to be a politician. He simply wanted to be famous. He tried his hand at being an artist, then a playwright, then a composer of opera. In the end he found he had just one talent – oratory.

It was through his love of art, music, film, theatre and, most of all, opera, and his enthralment with the idea of almost

hypnotising

his audience with sounds and sights that were inspired by the culture – often very lowbrow – he embraced, that he developed the techniques which resulted in the great geometrical rallies, the night-time torchlight parades, and the Nazification of the German film industry. There was even a Hitler film in the offing, and for a while he intended to play himself. He was, he once confessed, an actor, and he learned to play the part of the

Führer

– how to talk, to stand, to move, to perform. Everything in his public life, and often in his private life as he came to believe his own publicity, was stage-managed. Even the war. He wanted to play the role of a general, and when he tried writing his own script of World War Two, he bombed.

By design rather than as a by-product of his image-building, out of the cult of personality grew his cult of celebrity. He knew no other way to become dictator than by performing. Fame was more important to him than governing, although in his mind they became one and the same thing. Culture and art became politics. Even suicide was a macabre element to his celebrity, his legend and his sense of immortality, which were all irrevocably connected to the final act of his life-long drama; he would write his own ending.

Hitler completely absorbed himself in his cult of celebrity, and his most favoured actors, musicians, writers and other artists could be absorbed into his cult and become great celebrities themselves. All they had to do was promote Nazi ideology. Those that did were permitted to work, and some were pampered and preened into stars, and the public were virtually expected to pay to see the great stars. Artists who didn’t support Hitler’s ideas were, at best, denied work and, at worst, sent to the camps. Jews never had the luxury of either option. The ‘Jewish question’ is one of the most deplorable aspects of Hitler’s claim to fame.

The German film industry in particular was encapsulated by this cult of celebrity because it was the modern medium of the age. Under the Nazis, cinema became a weapon. Entertainment became

policy, and the greatest movie celebrities were advocates for

everything

Hitler stood for. The extermination of an entire race, played out against the magisterial music of Richard Wagner, whose works were the inspiration for Hitler’s new world, became the backdrop for Hitler’s own reality show, in which his name was above the title and every celebrity in Germany was a guest star.

The cult of celebrity became the cornerstone of Hitler’s Nazism – and Hitler loved celebrities, as did his publicist Joseph Goebbels, who ran the German film industry. Despite all their assertions and pretensions about art and culture, these arbiters of taste used their cult for their own sexual obsessions. Starlets and beautiful actresses were as much a sexual commodity in Nazi Germany as they were in Hollywood.

In Aryan Germany, Hitler governed with theatrical tricks. In ancient Rome the emperors gave the people the spectacle of the games to make them love the Caesars, and, taking his cue from them, Hitler gave his people the spectacle of Nazi culture and became their beloved

Führer

. At the heart of his style of

government

, backed by military and paramilitary might, was his Nazi cult of celebrity. He had nothing else to offer. In the end his obsession with fame led him into grand illusions that were merely delusions, and resulted in the deaths of around sixty million people.

I

f Hitler had nothing better to do, and usually he didn’t, he could be found at Berlin’s

Universum Film AG

– better known as UFA, Germany’s largest film studio at Babelsberg, which was just outside Berlin, near Potsdam – mingling with the stars. A film director at UFA, Alfred Zeisler, recalled that Hitler visited the studio very frequently. He loved to watch scenes being filmed, and he asked about new plots and new talent, and also about the technical aspects of film-making. Zeisler said that Hitler had a very good grasp of the film-making process and asked extremely intelligent questions about some of the technical problems involved. Hitler also enjoyed coming to the studios to have lunch or dinner in the restaurant of the Film Institute, where actors and actresses gathered.

1

It wasn’t as though Hitler didn’t have enough to occupy his mind in 1933, having, that year, become Germany’s

Führer

, but he cared nothing for politics, or for governing Germany. He had ministers to do all that. Hitler was obsessed with celebrities. And he knew that of them all, he was the greatest celebrity.

The most important thing he could do every day was satisfy his starstruck craving by being among his favourite film stars, and if it so happened that he couldn’t escape from the Reich Chancellery, he would get on the phone to the studio, as Zeisler recalled, to find out about films being made, and the actors in them, or just for general news about what was happening at the studios. Zeisler often wondered when Hitler had the time to devote himself to affairs of state because he spent so much time either at the studios, or on the telephone, or looking at films – there seemed little time left for anything else.

At the Berghof, Hitler’s mountain retreat, his young mistress Eva

Braun was left to her own devices while he was away working, or so he claimed, though he did very little real work as Chancellor of Germany. Eva was a good actress and might have actually been happy if Hitler had allowed her to actually be an actress, but he forbade her that pleasure. ‘I heard she wanted to be in films. Hitler said no,’ recalled German actor Curd Jürgens. ‘He didn’t want his girlfriend to be a film star, but he wanted to have film stars to be his girlfriends.’

2

Fringe benefits came with being the

Führer

. It was well known among the film community, where secrets were kept through fear, that he enjoyed the company of beautiful starlets. Hitler frequently called Alfred Zeisler at the UFA studio to ask for young starlets to keep him company in the Reich Chancellery. Zeisler duly sent them along, often in pairs, and was naturally very curious about what actually happened in the Reich Chancellery between Hitler and the pretty young women he sent, so one day in 1934 he asked two chorus girls he had procured for the

Führer

what had taken place the previous evening. They told him all that happened was that Hitler sat and bragged the whole evening, telling them how he was going to annex Austria and was going to build up the biggest army in the world and then reinforce the Rhineland. The girls said they thought Hitler ‘extremely odd’. Zeisler concluded that Hitler’s only intention was to impress the girls with his greatness and power.

3

Zeisler’s claims that he provided Hitler with female stars for company are given some credence by Walter C. Langer,

4

who in his famous psychological study of Hitler said Hitler often requested the studios to send over actresses whenever there was a party in the Chancellery. He seemed to get ‘an extraordinary delight’ in fascinating these girls about what he was going to do in the future, and he also reeled out ‘the same old stories’ of his past. He enjoyed impressing the girls with his power by ordering the studios to give the girls better film roles. Like a real movie mogul, he often promised them that he would personally see to it that they were given starring roles. Langer reported that men who, like him, have

associations with ‘women of this type’ did not go beyond that point; i.e., to have sexual intercourse with them.

5

These encounters with stars and would-be stars, at the studio or in some secret room in the Reich Chancellery, would seem to indicate that Hitler veered erratically from being a starstruck fan to some kind of impotent despot who wanted to impress and scare little girls; he was certainly known to form attachments to much younger women than himself who were vulnerable and whom he could dominate.

It all came down to power. Just having lunch with the stars was more than him being a fan having fun – which was certainly part of it – but it was a demonstration of his power; Germany’s biggest stars – and this also applied to musicians, writers and other artistes – for whom millions would kiss the ground they walked on all demonstrated their devotion to him, either through sincere admiration or out of fear, and their endorsement of him helped enormously to win the endorsement of the country long before John F. Kennedy was being elevated to the White House in 1961 by Frank Sinatra and his Rat Packers and other celebrities. Since then the world of politics has become a platform for celebrities, and the politicians themselves have become celebrities. In 1933, Hitler was doing all that. He had only to command celebrities to attend massive public events where he was the star attraction, or to

functions

where he could impress or bore them with one of his famous monologues about his latest plans, and they duly complied. That was a price they paid for the privilege of enjoying all the perks of Hitler’s cult of celebrity.

The power he had over the young starlets is apparent. And

probably

not as harmless as it might have seemed to the two chorus girls who only had to endure Hitler’s boastings. One famous actress endured much more, and paid the ultimate price.

In 1937 Germany was shocked by the news that actress and singer Renate Müller had died at the age of just thirty-one. Her body was found on the pavement outside a hotel on 7 October. She had fallen from the third-storey window of a hotel, and died instantly.

The blue-eyed beauty had starred in more than twenty German films, including

Viktor und Viktoria

in 1933, which was one of her biggest successes – and was remade in 1982 as

Victor Victoria

with Julie Andrews. Renate Müller was regarded by the National Socialists as an ideal Aryan woman and, in light of Marlene Dietrich’s defection to Hollywood, was courted and promoted as one of Germany’s leading film actresses.

She was already a star when Hitler came to power, and was pressured by Joseph Goebbels, who, as President of the

Reichskulturkammer

, which presided over the German film

industry

, to appear in some of his personally commissioned pro-Nazi anti-Semitic films. She resisted, so he put her under surveillance by the Gestapo, who established she had a Jewish lover. She finally gave in to Goebbel’s demands, and in 1937 she starred in the blatantly anti-Semitic

Togger

.

Her death was officially classified a suicide. The exact details of her death and the minutes leading up to it have become a matter of much conjecture. Several Gestapo officers were seen entering the hotel shortly before she died, and it was suggested either that she was murdered by Gestapo officers who threw her from a window, or that she panicked when she saw them arrive and jumped. Goebbels wanted the public to believe she had been emotionally unstable and had a drug addiction.

Theories for her possible murder include her lack of cooperation with Goebbels, her love affair with a Jew, and the regime’s fear that she was going to turn traitor and leave Germany as Dietrich had done. What is certain is that there was a cover-up about her death. The absolute truth will never be known, and her death remains as much of a mystery in the annals of the German film world as Marilyn Monroe’s has in Hollywood. Renate’s sister Gabriele always maintained that her death was due to post-operative complications on her knee, but that never explained how her body came to be on the pavement.

Almost the moment Renate Müller’s body was discovered, Goebbels realised he had a public relations disaster on his hands.

The first story that went out over the radio was that the cause of her death was epilepsy and that she had fallen from a window of a hospital. At some point, this hospital became a hospital for the mentally sick, suggesting Müller was mentally ill, or had had a breakdown. Goebbels spread rumours that she had become addicted to morphine, and was an alcoholic. The true story, of the fall from the hotel window, was only revealed later.

Goebbels saw to it that her funeral at the

Parkfriedhof Lichterfelde

on 15 October was held in private, and her adoring public was barred. Her possessions were confiscated and sold even though her parents and her sister were alive. Some years later, according to unconfirmed reports, they were all buried in the same grave as Renate, suggesting the family were all silenced.

Without resorting to possible murder, terrorisation and

extortion

, Goebbels acted much in the same way as Hollywood mogul Adolph Zukor once did when one of his top directors at Famous Players, William Desmond Taylor, was found murdered in 1922. Zukor ordered a cover-up so that the police were unable to ever charge anyone because Zukor knew that the identity of the killer – which became an open secret in Hollywood – would reveal facts about Taylor’s life which he wanted to keep from the public because of the shocking scandal it would cause. It seems likely that, for similar reasons, Joseph Goebbels, playing the part of the amateur movie mogul, did the same when Renate Müller died; she might have known some of Hitler’s most deviant secrets.

The full truth about her last years and death has never been fully uncovered, and there has been much unconfirmed information and clearly designed misinformation, as was the case with Monroe. Müller might have had a breakdown in 1933 due to the stress of trying to keep her weight down, and illness might have interrupted filming in 1934 – it was said to be epilepsy – but despite reports that her career was sporadic from then on due to whatever illness she might have had, she actually starred in four films during 1935 and 1936, and her last film in 1937,

Togger

, commissioned by Joseph Goebbels.

Albert Zeisler knew of Müller’s secret. On one occasion when Hitler called and asked Zeisler for the company of a pretty actress, possibly in 1935, or before, he sent Renate Müller. Quite why Zeisler chose her isn’t clear but it is very likely that Hitler asked for her. Whether she went under duress or from sheer admiration for Hitler isn’t obvious; according to Zeisler, she was prepared to have sexual relations with Hitler.

At the Reich Chancellery, Hitler took great delight in telling her that he had made a thorough study of medieval torture methods and was modernising them with the intention of introducing them to Germany. He described these methods to her – methods which were later adopted by the Gestapo – in such explicit detail that she was horrified to the point where she felt her ‘flesh creep’.

6

Renate did her best to seduce him without success; she told Zeisler that he seemed uninterested in sex. However, on another occasion, he seemed to become excited and she thought they would finally make love, but instead he jumped to his feet, raised his arm in the Nazi salute and bragged that he could hold his arm that way for an hour and a half without tiring, unlike Göring, who, Hitler said, could not hold out his arm even for twenty minutes.

She arrived one morning at the studio in a very depressed state and when Zeisler asked her what was troubling her she told him she had been with Hitler at the Reich Chancellery that night and she had been sure they were going to have sexual intercourse. They had got as far as undressing, but then Hitler fell to the floor and begged her to kick him. She resisted but he pleaded with her and condemned himself as unworthy and grovelled on the floor in an agonising manner. As disgusted as she was, she gave in and kicked him, which excited him. He begged for more and,

masturbating

, said it was better than he deserved and that he was not worthy to be in the same room as she. When he was satisfied, he suggested they got dressed, and he thanked her warmly for a pleasant evening.

7

This tale has been often regarded as pure fiction by some

historians

because Zeisler hated Hitler for making him leave Germany after he refused to make films that would promote Nazi ideology.

While it certainly appears to be almost too sensational, presenting a clichéd image of a mad dictator who can only enjoy perverse sex, Hitler did struggle with a compulsion to completely degrade himself whenever he felt some kind of affection for a woman. Nazis Ernst Hanfstaengel, Otto Strasser and Herman Rauschning all reported that whenever Hitler was smitten with a girl, even in company, he tended to ‘grovel at her feet in a most disgusting way’.

8

Like almost all the girls Hitler was attracted to, Renate Müller was blonde. Zeisler recalled ‘another tall blonde called Loeffler’ who became involved with Hitler, but after a while she ran off with a Jewish man and lived in Paris, which upset Hitler so much that for some time he did not even bother calling the studio to ask for girls.

9

For years, Hitler’s sexuality has been a matter of debate and

disagreement

. Suggestions that Hitler was homosexual appear to be unfounded but may well have been based on what was observed as his feminine characteristics – his gait, his mannerisms and even his choice of art as a profession were once interpreted as feminine manifestations. With the possible exception of Heinrich Hoffmann, the Nazi Party’s official photographer, and Hitler’s personal

adjutant

, no one knew the nature of his sexual activities, causing much conjecture in party circles, with some believing that he was

sexually

‘normal’ while others suggested that he was immune to sexual temptation. Others thought he was homosexual because many of the party’s inner circle in the early days were known

homosexuals

. Rudolf Hess was known as ‘Fraulein Anna’. For a long time Hitler ignored the fact that many in the SA leadership were homosexuals, including Ernst Röhm. Röhm was well aware that Hitler was attracted to the female form, and one time remarked in Hitler’s presence, ‘He is thinking about the peasant girls. When they stand in the fields and bend down at their work so that you can see their behinds, that’s what he likes, especially when they’ve got big round ones. That’s Hitler’s sex life.’

10