Hitler's Beneficiaries: Plunder, Racial War, and the Nazi Welfare State (20 page)

Read Hitler's Beneficiaries: Plunder, Racial War, and the Nazi Welfare State Online

Authors: Götz Aly

BOOK: Hitler's Beneficiaries: Plunder, Racial War, and the Nazi Welfare State

13.56Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

The goods were also used as rewards, enabling recipients to maintain or renovate their homes in style. The addressees of one freight shipment included a “Obersturmführer Tychsen (Recipient of the Knight’s Cross with Oak Leaves),” “Captain Ninnemann,” “Captain Adamy,” “Sturm-führer Brehmer (Recipient of the Knight’s Cross),” and “Reich Post Office (Postal Check Office) Director, Berlin, Guilleaume.” In another instance of personaprofiteering, a party comrade von Ingram, “together with other bearers of the Knight’s Cross,” received “proceeds” from the furniture operation.

96

Special recognition was paid to “veterans and party members with especially distinguished service records,” who were given homes and businesses “previously owned by Jews” in order to “support them in the establishment of an economically secure existence.”

97

96

Special recognition was paid to “veterans and party members with especially distinguished service records,” who were given homes and businesses “previously owned by Jews” in order to “support them in the establishment of an economically secure existence.”

97

Those responsible for carting off Jews’ furniture closely coordinated their activities with the offices that organized the deportations. Nevertheless, the Security Police occasionally had to intervene to prevent the looters from arriving at residences before they had been vacated and causing resistance among the Jews scheduled to be relocated. In late 1943, von Behr complained that the Security Service in the Belgian city of Liege had all but stopped taking Jews into custody. “Because of the major bombing damage recently in the Reich,” von Behr wrote, “the demands upon my office have substantially increased. I would urge that the Jewish operation in Liege resume at the earliest possible opportunity so that the securing of Jewish furniture and its transport to Reich can proceed.” Six months later, on June 13, 1944, after nothing had been done, von Behr once again prodded the Security Police on behalf of his ethnic comrades. “In the interest of bombed-out Germans,” he demanded the arrests of the sixty remaining Jewish families living in Liège.

98

98

THE FURNITURE operation also involved confiscating shipping containers full of the belongings of Jews who had emigrated. Great numbers of these containers, known as “lift vans” or simply “lifts,” had been stranded in the ports of Antwerp, Rotterdam, and Marseilles at the start of the war. In the wake of one heavy aerial bombardment of Cologne in summer 1942, the Reich Finance Ministry, which considered these effects to be German state property, transferred a thousand such lifts from Antwerp to the Cologne city administration.

99

Containers from Rotterdam arrived simultaneously at Cologne’s port, and from there some of their contents were transported on to Münster, Mannheim, and Lübeck. Goods not immediately needed were stored, by arrangement with the Finance Ministry, as an “emergency reserve.”

100

Berlin was the primary recipient of containers confiscated in occupied Trieste and Genoa after the official Italian government had turned against Germany and realigned itself with the Allies.

101

The contents of many of the containers that had been stored in Hamburg in the spring of 1941 were auctioned off, with the lion’s share being bought by the Social Services Administration. The goods were then distributed to various warehouses throughout the city as a “handy reserve in case of catastrophe.”

102

The practice of confiscating emigrants’ belongings stuck in transit was typical throughout Germany.

103

99

Containers from Rotterdam arrived simultaneously at Cologne’s port, and from there some of their contents were transported on to Münster, Mannheim, and Lübeck. Goods not immediately needed were stored, by arrangement with the Finance Ministry, as an “emergency reserve.”

100

Berlin was the primary recipient of containers confiscated in occupied Trieste and Genoa after the official Italian government had turned against Germany and realigned itself with the Allies.

101

The contents of many of the containers that had been stored in Hamburg in the spring of 1941 were auctioned off, with the lion’s share being bought by the Social Services Administration. The goods were then distributed to various warehouses throughout the city as a “handy reserve in case of catastrophe.”

102

The practice of confiscating emigrants’ belongings stuck in transit was typical throughout Germany.

103

The officials responsible for dispersing the property stolen by the state were the heads of local finance departments. The process always followed the same pattern: local officials would compensate bombed-out citizens with money and vouchers for lost household effects, clothing, and so forth in the name of the central Reich government. Applicants would also receive identification cards allowing them to buy replacement furnishings directly or at auctionoceeds were then handed back to the Reich. In budgetary terms, it was a break-even proposition for the state and its citizens at the expense of dispossessed owners, many of whom had been murdered. An official government notice in the Oldenburg city paper on July 24, 1943, gives an idea of how such sales and auctions proceeded: “Cash sale of porcelain, enamelware, beds, and linens on Sunday, July 25, 1943, at the Strangmann Restaurant in Hatterwüsting. Begins at 4:00 P.M. for noncompensated victims of bombings, at 4:30 P.M. for large families and newlyweds, and at 5:00 P.M. for the general public.” The announcement was signed by the mayor. Between 1942 and 1944, the city of Oldenburg took in exactly 466,617.39 reichsmarks from such sales. The city treasurer transferred the money to the Reich’s coffers. It was entered in the books under the heading “general administrative revenues.”

104

104

Because most of the supplies dispatched to northwestern Germany came from the homes of Jews in Holland, the residents of Oldenburg referred to these goods as “Dutch furniture.” By summer 1944, German relief workers—with the help of the Dutch delivery company A. Puls—had transported the inventory of 29,000 residences to the Reich. The furniture operation in the Netherlands had commenced with a formal ordinance from the Central Office for Jewish Emigration, which had been set up by the Security Service. The announcement of that ordinance in the

Joodsche Weekblad

(Jewish Weekly) on March 20, 1942, read: “Any Jew who lives in a residence he owns, rents, or otherwise uses is required, by paragraph 3 of the Ordinance of the General Commissioner for Security Affairs of September 15, 1941, to obtain written permission from the Jewish Council in Amsterdam before removing any furniture, furnishings, household objects, or other possessions.” Violators were threatened with serious consequences.

105

Joodsche Weekblad

(Jewish Weekly) on March 20, 1942, read: “Any Jew who lives in a residence he owns, rents, or otherwise uses is required, by paragraph 3 of the Ordinance of the General Commissioner for Security Affairs of September 15, 1941, to obtain written permission from the Jewish Council in Amsterdam before removing any furniture, furnishings, household objects, or other possessions.” Violators were threatened with serious consequences.

105

In the summer of 1943, shipments of furniture from Prague were arriving in the Ruhr Valley, while used clothing and linens from Prague were turning up in Cologne. In a richly illustrated report, the head of the Trust Office (Treuhandstelle) in Prague, which took goods from the homes of thousands of deported Jews, bragged about how diligently the items had been collected, repaired, and stored. The report was titled “From Jewish Wealth to Collective Property.” By late February 1943, the leftovers from the Aryanization of Prague had been piled up and cataloged in city warehouses: 4,817 bedroom sets, 3,907 kitchen sets, 18,267 armoires, 25,640 armchairs, 1,321,741 household and kitchen items, 778,195 books, 34,568 pairs of shoes, 1,264,999 items of linen and clothing, and so on. To the Trust Office employees, these stocks represented an “irreplaceable” wartime reserve.

106

106

Deported German Jews were allowed to take fifty kilograms of personal effects with them. Understandably, deportees usually favored items of value and warm clothes. But in many cases, the suitcases and packages containing these belongings remained behind, after their owners were deported. On June 24, 1942, the freight cars of the train that took Jews from Königsberg to their deaths in the Maly Trostinec extermination camp near Minsk were uncoupled and never left the station. A similar scene played itself out on April 22,1942, in Düsseldorf. Five days later, after the deportees’ belongings—which included everything from hot-water bottles and woolen socks to nylons, overcoats, suits, and shoes—had been sorted through, they were handed over to the local Nazi welfare office. Other items among the luggage of the ted Jews—gauze and bandages, soap powder, hard and liquid soap, razor blades, shaving lotion, shampoo, hair oil, ethanol, matches, eau de cologne, salves, shoe polish, sewing sets, toothbrushes, smoking and chewing tobacco, cigarettes, cigars, tea, coffee, cocoa, sweets, sausages, oranges, lemons, and other food—were delivered to the district office of the German Red Cross, a veterans’ home, a reserve military hospital, and the military canteen at Düsseldorf’s main train station.

107

107

Hamburg, which because of its size and its proximity to Britain was hit especially often and hard by RAF raids, represents a case to itself. In February 1941, at the behest of the local gauleiter, the Gestapo confiscated 3,000 to 4,000 lifts in Hamburg’s duty-free port and ordered the contents immediately sold off by a Hamburg auction house. The auctions proceeded according to the same criteria of need as in Oldenburg or Aachen, but Hamburg enjoyed a uniquely steady flow of supplies. In addition to the previously mentioned 2,699 freight cars of furniture from West European Jews, forty-five ships transported 27,227 tons of “Jewish commodities” from Belgium and Holland to the city. A total of 100,000 bidders from Hamburg and the surrounding area—most of them women whose husbands were serving in the war—acquired items from these deliveries of stolen property. Around 100,000 households in and around Hamburg thus profited from the sale of furniture, clothing, and thousands of everyday household items and amenities that had previously belonged to some 30,000 Jewish families.

108

108

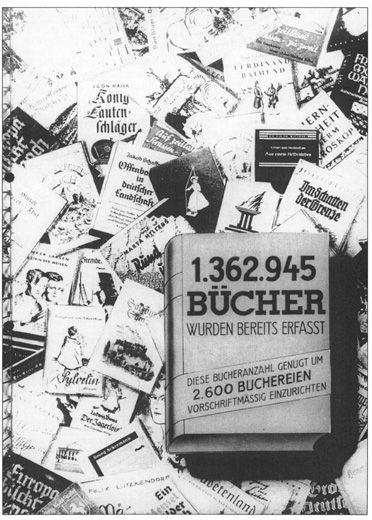

Cover of the report from the Trust Office in Prague, 1942. “From Jewish Wealth to Collective Property: After emigration, remaining assets—especially domestic furnishings and personal effects—are transferred.” (Landesarchiv, Berlin)

The poster reads: “1,362,945 books have already been seized. That’s enough to fully equip 2,600 local libraries.” The private libraries of Czech Jews were utilized for the improvement of German public education. (Landesarchiv, Berlin)

After the war, librarian Gertrud Seydelmann recalled the auctions in Hamburg’s working-class districts:

Ordinary housewives suddenly wore fur coats, traded coffee and jewelry, and had imported antique furniture and rugs from Holland and France. . . . Some of our regular readers were always telling me to go down to the harbor if I wanted to get hold of rugs, carpets, furniture, jewelry, and furs. It was property stolen from Dutch Jews who, as I learned after the war, had been taken away to the death camps. I wanted nothing to do with this. But in refusing, I had to be careful around those greedy people, especially the women, who were busily enriching themselves. I couldn’t let my true feelings show. The only ones upon whom I could exercise a cautious influence were those whose husbands I knew had been committed Social Democrats. I explained to them where these shipments of excellent household wares came from and cited the old maxim “Ill-gotten gains seldom prosper.” And they acted accordingly.

109

By conservative estimates, some 100 million reichsmarks’ worth of goods (the equivalent of $700 million today) was stolen from France alone in the first year of the furniture operation. The total booty in furnitre stolen from Holland reached similar proportions.

110

The actual amount of money taken in, however, was far less since prices for buyers in Germany were lower than the goods’ actual market value. The operation was not primarily intended to bring money into the state’s coffers. In one report, organizers bragged: “The furniture operation of the Western Office [of the Reich Ministry for the Occupied Eastern Territories] is devoted entirely to providing for the most seriously hit victims of the bombings and offers considerable price relief on the German furniture market. There is no underestimating the psychological effect of the swift provision of household furnishings on the ethnic comrades affected. To take what has become a real-life scenario: if, after large attacks, hard-hit families can be transferred in a matter of hours to fully furnished apartments, it must be seen as a significant factor in maintaining war morale.”

110

The actual amount of money taken in, however, was far less since prices for buyers in Germany were lower than the goods’ actual market value. The operation was not primarily intended to bring money into the state’s coffers. In one report, organizers bragged: “The furniture operation of the Western Office [of the Reich Ministry for the Occupied Eastern Territories] is devoted entirely to providing for the most seriously hit victims of the bombings and offers considerable price relief on the German furniture market. There is no underestimating the psychological effect of the swift provision of household furnishings on the ethnic comrades affected. To take what has become a real-life scenario: if, after large attacks, hard-hit families can be transferred in a matter of hours to fully furnished apartments, it must be seen as a significant factor in maintaining war morale.”

Thank-you notes written by recipients “from all social classes” to the offices responsible for collecting and distributing the goods attest to the psychological effectiveness of the emergency relief program. If relief volunteers are to be believed, the Western Office achieved “enormous popularity among all segments of the population.” Its activities soon came to be seen not only as “important to the war effort” but also “important for victory among our comrades suffering from privation.” Despite increasing transport difficulties, freight trains and barges full of looted household effects took “top priority” when space and time on rails and waterways were allocated.

111

111

Other books

Will You Still Love Me Tomorrow? by Claudia Carroll

Unbound by Olivia Leighton

The Hanging Wood by Martin Edwards

The Aviary by Wayne Greenough

How Not To Be Popular by Jennifer Ziegler

Black Storm by David Poyer

Queen of Angels by Greg Bear

To Catch a Creeper by Ellie Campbell

In Darkling Wood by Emma Carroll

The Devil's Banker by Christopher Reich