Hitler's Beneficiaries: Plunder, Racial War, and the Nazi Welfare State (25 page)

Read Hitler's Beneficiaries: Plunder, Racial War, and the Nazi Welfare State Online

Authors: Götz Aly

BOOK: Hitler's Beneficiaries: Plunder, Racial War, and the Nazi Welfare State

4.19Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

When German troops occupied the north of Italy, its former ally, in September 1943, more than a half million POWs were taken back to the Reich as forced laborers. Once again, the state confiscated part of their wages, using what was by then the established system of diverting money from occupation budgets to pay foreign workers’ families. German companies using forced labor were required to transfer wages to an account at the Deutsche Bank. From there the money was sent on to the “wage savings account” at the German Settlement Bank. These sums, of course, never found their way back to Italy. Instead, the economics minister ordered: “They are to be held in Berlin, where they will be kept at the disposal of the Italian government. How to use these sums of reichsmarks is a decision that will be made at a later point in time.” In reality, these assets were secretly converted into German treasury bonds, which would have been used to pay concocted external occupation costs had Germany won the war. The records of monetary transfers to the general account at the Deutsche Bank for individual Italian workers determined the payments made by the Banca del Lavoro in Italy to those workers’ families. To raise money for those payments, the Italian finance minister was required to provide the bank “with adequate credit.”

5

5

THE PROCEDURES governing forced laborers from Poland and the Soviet Union were far harsher. An order issued in 1942 described what German soldiers were to do with the meager belongings of male and female workers taken prisoner in rural Ukraine: “Possessions left behind as well as any cash” were to be handed over to the village elder, who was in turn to sell the material assets. “Animal inventory (horses, cows, pigs, sheep, chickens, geese, etc.) as well as hay, straw, and field crops” were to be “immediately” offered up for sale to the economics command of the local Wehrmacht division. The village elder was required to transfer the revenues from such sales, together with any confiscated money, to a sham account at the German treasury. The treasury would then, theoretically, refund the money when rural workers returned home so that they could use it to “reacquire livestock and seed materials.” No one knows what would have actually happened to Soviet forced laborers in the event of a German victory. As it was, their assets were converted into cash that flowed directly into the Reich treasury.

6

6

Once they arrived in Germany, forced laborers were assigned to German companies, which were required to pay their new workers wages at the low end of the scale. On August 5, 1940, the Reich Defense Council issued a decree requiring Polish workers in Germany to pay a “supplemental social compensation fee in addition to the normal income tax.” (The draft version of this edict dated back to 1936, when the Finance Ministry considered levying a special “performance compensation fee” on wages earned by German Jews.)

7

The revenues from the special fee on Polish laborers went directly to the Reich. Meanwhile, the Finance Ministry secured permission to extend the levy to other particularly disadvantaged groups. Before long, Jews and Gypsies were also compelled to pay it.

8

7

The revenues from the special fee on Polish laborers went directly to the Reich. Meanwhile, the Finance Ministry secured permission to extend the levy to other particularly disadvantaged groups. Before long, Jews and Gypsies were also compelled to pay it.

8

According to the first implementation decree that followed, the levy applied to all Poles living within Germany, even those who were voluntarily employed, as well as those Poles who lived in parts of Poland annexed by the Reich. An exception was made for Poles who worked in agriculture since the wages negotiated for them were, in comparison with the German standard, particularly meager: room and board plus pocket money of between 8.50 and 26.50 reichsmarks per month.

9

The supplemental social compensation fee was set at 15 percent of workers’ gross wages. The official justification for the levy was that Polish workers did neither social nor military service, nor did they pay contributions to the German Labor Front or make compulsory donations to the main Nazi charity, the German Winter Relief Fund.

10

9

The supplemental social compensation fee was set at 15 percent of workers’ gross wages. The official justification for the levy was that Polish workers did neither social nor military service, nor did they pay contributions to the German Labor Front or make compulsory donations to the main Nazi charity, the German Winter Relief Fund.

10

In addition, voluntary and involuntary Polish workers were automatically assigned, without exception, to the top income tax brackets (categories I and II). Categories III and IV, which had been introduced to benefit poor German families, “were ruled out as a matter of principle.” This discriminatory tax rule had been imposed on Jews on February 17, 1939, one year after the German finance minister had stripped them of eligibility for tax deductions for children.

11

Jews were automatically assigned to category I. (The rules governing Soviet workers were repeatedly modified, but never to the benefit of German employers or the laborers themselves.)

11

Jews were automatically assigned to category I. (The rules governing Soviet workers were repeatedly modified, but never to the benefit of German employers or the laborers themselves.)

In practice the tax policy operated as follows: a Jewish man with a wife and one child who performed forced labor at Daimler-Benz in 1942 received a monthly wage of 234 reichsmarks. He was required to pay 108 marks in taxes and contributions to social welfare programs to which he and his family were theoretically entitled. Non-Jewish colleagues who received the same wages had to pay only 9.62 marks in taxes and 20.59 marks in contributions.

12

The amounts deducted from the wages of Jews—as well as of Gypsies and forced laborers from Eastern Europe—were thus more than triple those demanded of German workers. The Reich was able to double its wage tax revenues during the latter half of World War II on the backs of involuntary workers assigned to German industry and voluntary laborers in the annexed parts of Poland. A portion of the remaining wage packet was earmarked to be sent home to workers’ families. The German employer would pay an equivalent sum into the general bank account set up by the Finance Ministry for worker remittances. The General Government of Poland was then required to pay out the earnings to the families in Poland. In this way the Reich compelled the Polish people to pay for labor performed on German territory.

12

The amounts deducted from the wages of Jews—as well as of Gypsies and forced laborers from Eastern Europe—were thus more than triple those demanded of German workers. The Reich was able to double its wage tax revenues during the latter half of World War II on the backs of involuntary workers assigned to German industry and voluntary laborers in the annexed parts of Poland. A portion of the remaining wage packet was earmarked to be sent home to workers’ families. The German employer would pay an equivalent sum into the general bank account set up by the Finance Ministry for worker remittances. The General Government of Poland was then required to pay out the earnings to the families in Poland. In this way the Reich compelled the Polish people to pay for labor performed on German territory.

But there were limits to how much money Berlin could swindle from Poles this way. As early as the fall of 1940, the measure had drawn complaints from the occupation administrators, who sought to stabilize conditions in Poland, if only for Germany’s benefit. The German general governor in Poland, Hans Frank, vehemently protested that the Finance Ministry was “cutting the wages” of Polish workers in the Reich and that “the treasury was hoarding the surplus, if indeed there is a surplus, entirely for itself in the form of social benefits contributions.” The result, Frank complained, was that the General Government “had to use state funds for the maintenance of families whose providers were working within the Reich.”

According to Frank, Hitler himself was “quite astonished at this development.” In Frank’s account, the Führer warned: “If the financial administration of the Reich is indeed not transferring the wages earned by Polish workers in the Reich to the General Government but is instead using them covertly within the Reich, that is an absolutely unacceptable situation.”

13

Individual German companies and the gauleiters in East Prussia also objected that Polish workers were being too harshly exploited. The system, they complained, removed all incentives to work harder and more conscientiously.

14

In 1943, the Reich Central Security Office demanded that “all instances of discrimination against Poles be avoided for the time being” in the face of “the increased intractability of the Polish resistance movement.”

15

13

Individual German companies and the gauleiters in East Prussia also objected that Polish workers were being too harshly exploited. The system, they complained, removed all incentives to work harder and more conscientiously.

14

In 1943, the Reich Central Security Office demanded that “all instances of discrimination against Poles be avoided for the time being” in the face of “the increased intractability of the Polish resistance movement.”

15

Yet on top of all the taxes and social benefits contributions, Polish and Soviet forced workers’ wages were docked a further 1.50 reichsmarks per day for room and board in the labor camps. According to one economist’s estimate, only around 10 reichsmarks were left of a Russian or Polish worker’s weekly wage of 40 marks, once taxes, contributions, and room and board had been deducted. The economist warned, however, that “given the shortages of consumer goods in the Reich, [we should prevent the workers] from spending the entire sum.”

16

16

To combat this potential problem, the Economics Ministry developed an Eastern Workers’ Savings program, which “utilized the simplest possible form of savings bonds.” Under the system, the payroll departments of German companies were issued special savings bonds “with relief printing and denominations in Arabic numerals.” The companies were then required to pay the equivalent amount to the Reich treasury. In theory, forced laborers would have been able to redeem their savings, with 2 percent interest, when they returned home. But the wording of the relevant legislation was vague: “the amount saved” was to be made available “to the saver or a member of his family, subject to the specific regulations of the Reich minister for the occupied eastern territories or the Wehrmacht High Command.”

17

17

The bank that had ostensibly issued the savings bonds, which were given to all the forced laborers from the Soviet Union, was the Central Economic Bank of Ukraine.

18

The funds paid by German companies were transferred to that institution’s purely fictitious Berlin office. There, they were recorded as a single lump sum rather than deposited into individual accounts. The hypothetical paying out of this money was “to proceed in the native currency of each particular country.” The funds could not Ukithdrawn by workers while they remained in Germany, only once they had returned home.

18

The funds paid by German companies were transferred to that institution’s purely fictitious Berlin office. There, they were recorded as a single lump sum rather than deposited into individual accounts. The hypothetical paying out of this money was “to proceed in the native currency of each particular country.” The funds could not Ukithdrawn by workers while they remained in Germany, only once they had returned home.

The Berlin office of the Central Economic Bank of Ukraine was one of many fronts for the Reich treasury. When one considers how Germany dealt with “ethnic aliens” and how its Eastern European forced laborers were often worked to death in conditions of virtual slavery, the Eastern Workers’ Savings program emerges as just another way for the Reich to appropriate other people’s money. As historian Manfred Oertel writes: “Ultimately, all the taxes, contributions, and ‘savings’ of Polish and Soviet workers from their forced labor in Germany were a specific form of tribute” designated for the war chest of the Third Reich.

19

So, too, was the income Western European workers sent back to their home countries.

19

So, too, was the income Western European workers sent back to their home countries.

THE BUDGETARY advantages of using forced labor are obvious. It allowed the state treasury maximum access to workers’ wages, thereby stabilizing wartime finances, transferring burdens from German taxpayers, and—as a welcome bonus—protecting the tight market of available consumer goods from additional spending power. Had the Reich relied instead on the increased labor output of German women or on lengthened working hours, several additional billions of reichsmarks would have come into circulation. But there would not have been anything more to buy in stores. That would have put a strain on the reichsmark and possibly had a negative effect on popular opinion.

An examination of domestic wage taxes between 1941 and 1945 reveals that a considerable portion of revenues came from foreign laborers. The benefit to companies like Daimler-Benz and Krupp was hardly negligible, considering that foreign workers were paid 15 to 40 percent less than their German colleagues. But the benefit to the German people, the

Volks-gemeinschaft

, as embodied by the Nazi state, was far greater. In practice, the Reich appropriated 60 to 70 percent of the wages paid by those firms.

Volks-gemeinschaft

, as embodied by the Nazi state, was far greater. In practice, the Reich appropriated 60 to 70 percent of the wages paid by those firms.

Wage tax revenues from foreign labor for the period in question totaled 6.5 billion reichsmarks. (In the case of agriculture, Berlin kept wages artificially low, creating, as noted above, an indirect subsidy for farmers to the tune of at least 3.5 billion marks.) An average of 500 million marks came into the state annually through the confiscation of foreign worker remittances. That amounts to a total of an additional 2.5 billion marks, which the Reich recorded as “general administrative revenues.”

20

Assuming that the Eastern Workers’ Savings program brought in a further 500 million, then the state earned at least 13 billion marks—in today’s terms, $150 billion—from forced labor. The size of this figure belies the traditional historical assumption that it was companies that profited most from forced labor. Instead the exploitation was perpetrated on a far grander scale, by the whole of society itself. The billions in state revenues from forced labor took a significant load off ordinary German taxpayers. And this was only one of the advantages that individual “ethnic comrades” derived from their acceptance of a government campaign not only to wage war against others but to dispossess them of everything they had.

20

Assuming that the Eastern Workers’ Savings program brought in a further 500 million, then the state earned at least 13 billion marks—in today’s terms, $150 billion—from forced labor. The size of this figure belies the traditional historical assumption that it was companies that profited most from forced labor. Instead the exploitation was perpetrated on a far grander scale, by the whole of society itself. The billions in state revenues from forced labor took a significant load off ordinary German taxpayers. And this was only one of the advantages that individual “ethnic comrades” derived from their acceptance of a government campaign not only to wage war against others but to dispossess them of everything they had.

Few documents have survived in the German federal archive about the theft of wages and benefits from forced laborers and the benefits derived by the German populace. But one significant indicator of both is the level of subsidies paid out of the Reich’s general budget to social welfare agencies, which were perennially strapped for cash during the war.*

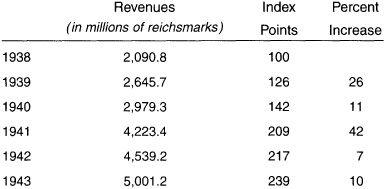

Table 1: State Subsidies to Social Welfare Programs, 1938–43

In table 1, the drastic decline in 1942 stands out. The obvious explanation is that the establishment of a forced-labor economy reduced the need for expenditures to keep the social welfare system afloat. The table shows that within the space of only three budgetary years the subsidies needed by Germany’s social welfare system had more than doubled. If that increase had continued unabated, state subsidies would have reached 2.14 billion marks by 1944, and 2.35 billion by April 1945.

Other books

The Incredible Adventures of Cinnamon Girl by Melissa Keil

Collected Poems by William Alexander Percy

Wonder by R. J. Palacio

Waiting For Forever (Beautiful Surrender, Part Four) by Ava Claire

Aven's Dream by Alessa James

Rough & Tumble by Kristen Hope Mazzola

Madeline Mann by Julia Buckley

Forever As One by Jackie Ivie

Feather in the Storm: A Childhood Lost in Chaos by Wu, Emily, Engelmann, Larry

Job: A Comedy of Justice by Robert A Heinlein