Hitler's Beneficiaries: Plunder, Racial War, and the Nazi Welfare State (40 page)

Read Hitler's Beneficiaries: Plunder, Racial War, and the Nazi Welfare State Online

Authors: Götz Aly

BOOK: Hitler's Beneficiaries: Plunder, Racial War, and the Nazi Welfare State

2.73Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

In mid-June 1943, at a “departmental meeting on Greece,” ministerial director Friedrich Gramsch, acting as Göring’s representative, was quoted as saying that he didn’t think the use of gold and currency was “at the time practical for the acquisition of services in Greece.” But Neubacher, who also took part in the meeting, insisted on “returning, if necessary, to this question in the course of developments” that could not be determined that day.

63

September saw a rapid deterioration in the currency situation, which had been relatively stable since the preceding December. This prompted Hans Graevenitz to contact Neubacher by telegram with a request for gold. “In order to stage an effective intervention,” he wrote, “a temporary allocation of further resources would be advisable.”

64

(The word “further” belies claims Graevenitz would make in self-defense after the war that at that point no gold had been appropriated.) As a temporary measure to shore up the drachma, the “military commander, with the support of the special emissary of the Foreign Office for Southeastern Europe,” confiscated the entire assets of Athens’s 8,000 Jews and transferred them “for administration to the Greek state.”

65

63

September saw a rapid deterioration in the currency situation, which had been relatively stable since the preceding December. This prompted Hans Graevenitz to contact Neubacher by telegram with a request for gold. “In order to stage an effective intervention,” he wrote, “a temporary allocation of further resources would be advisable.”

64

(The word “further” belies claims Graevenitz would make in self-defense after the war that at that point no gold had been appropriated.) As a temporary measure to shore up the drachma, the “military commander, with the support of the special emissary of the Foreign Office for Southeastern Europe,” confiscated the entire assets of Athens’s 8,000 Jews and transferred them “for administration to the Greek state.”

65

Initially Berlin refused to send any more gold, and inflation continued to rise in Greece, causing morale problems among German soldiers, whose pay was no longer sufficient to purchase all the things they wanted to buy. On November 13, 1943, the Luftwaffe’s Southeast High Command sent a telegram to Göring’s staff: “The German soldier sees that price gouging is going on with food that he himself cannot afford because he is not being given enough money. Occasional pay raises such as the one on November 11 are viewed as completely pointless. The German soldier would like to be able to purchase food in the area where he is serving, at least at Christmas, in order to send it back home to his family, since those on the home front suffer more from the war than the Greek population. The necessary consequence, since he is not able to purchase it normally, is black market wheeling and dealing of the most odious sort.” The general who wrote this communiqué called for “energetic measures” aimed at allowing his men “to send [at least] Christmas gifts back home.”

66

66

On November 8, a few days before the soldiers’ complaints reached Göring’s office, the topic had already been discussed at a high-level departmental meeting. Participating along with Neubacher were the economics minister, the finance minister, an the managing director and president of the Reichsbank, as well as Göring’s confidant Gramsch. Among a number of further measures they decided on to stabilize the Greek currency was the use of Reich gold reserves, which had been tried out in January 1943 in Romania. Beginning in November, the Reichsbank regularly transferred gold—a total of more than eight tons—to Athens via its Vienna branch. The deliveries were made by courier plane. By strategically selling off that gold, Reich officials responsible for the Greek economy were able to create a measure of stability for the inflationary drachma.

67

67

The deliveries began ten days after the November 8 meeting. Previously announced price hikes in Greece were canceled, and Wehrmacht intendants were instructed “to temporarily postpone nonessential purchases.”

68

A portion of the money saved went toward giving dissatisfied soldiers a substantial pay raise in December.

69

The curb on spending did not stop but did help slow inflation. Neubacher sanctimoniously promised that, while Greece would have to pay certain top-priority contributions in advance, the money would be debited to the occupiers. (He would later boast that because he had “kept this promise general enough, without specifying a repayment deadline or an interest rate,” the Reich had taken on no “inordinate commitments.”)

70

By the end of the German occupation of Greece, however, despite the airlift of gold and efforts to rein in spending, inflation was running at no less than 550 million percent.

71

68

A portion of the money saved went toward giving dissatisfied soldiers a substantial pay raise in December.

69

The curb on spending did not stop but did help slow inflation. Neubacher sanctimoniously promised that, while Greece would have to pay certain top-priority contributions in advance, the money would be debited to the occupiers. (He would later boast that because he had “kept this promise general enough, without specifying a repayment deadline or an interest rate,” the Reich had taken on no “inordinate commitments.”)

70

By the end of the German occupation of Greece, however, despite the airlift of gold and efforts to rein in spending, inflation was running at no less than 550 million percent.

71

Yet despite hyperinflation, which caused the drachma to collapse in the summer of 1944, the commissioner in charge of monitoring the Bank of Greece, Reichsbank director Paul Hahn, argued in his final report that he had succeeded in “preserving the drachma’s viability as a means of payment for as long as possible.” Doing so, Hahn added, had been “a matter of fundamental concern for the German Wehrmacht.”

72

72

After the war, those who had been responsible for the transfer of gold cited it as evidence of their humanitarian compassion. “In the middle of November [1943],” wrote Neubacher in his memoirs, “I began the gold campaign at the Athens exchange. . . . The Greeks were utterly surprised. No one had thought it possible that Germany would put gold on the market.”

73

Hahn described his own activities in similarly glowing terms. The Greeks, he wrote, had viewed the “flow of gold owned by the German occupiers” as a political act that compared favorably “with earlier financial aid measures from foreign countries,” such as Britain. The campaign, Hahn boasted, “earned respect and appreciation within Greek economic and financial circles.”

73

Hahn described his own activities in similarly glowing terms. The Greeks, he wrote, had viewed the “flow of gold owned by the German occupiers” as a political act that compared favorably “with earlier financial aid measures from foreign countries,” such as Britain. The campaign, Hahn boasted, “earned respect and appreciation within Greek economic and financial circles.”

Those circles, it must be pointed out, had turned a tidy profit from the gold transactions. Many leading Greek businessmen served as brokers and bought up tranches of gold at exchanges in Athens, Salonika, and, to a lesser extent, Patras. According to Hahn, the Reich turned to trusted Greek brokers to handle the sales. Transactions were carried out “via the Bank of Greece.”

74

74

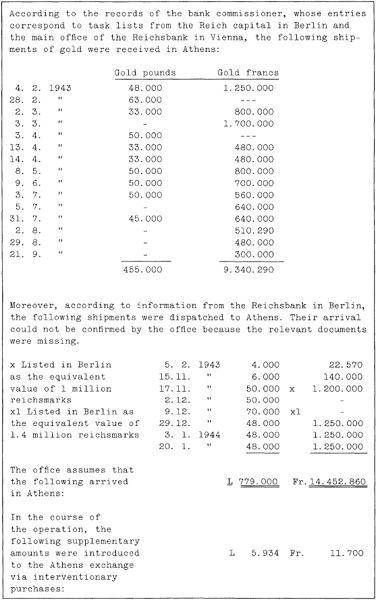

Hahn’s final report, written in the winter of 1944-45, summed up his three years as German bank commissioner at the Bank of Greece. That report was published, in slightly revised form, in 1957. His account contains a extensive description of the gold campaign. A careful examination of the document (see pp. 262-263), however, reveals that the first deliveries did not date from November 18, 1943, as a number of later apologists and Hahn himself in the text of the report claimed, but rather from February 4, 1943. In addition, Hahn divided gold received into several rubrics. A set of columns at the bottom of the page lists deliveries, most of them after November 1943. They are described as having been “dispatched” from the Reichsbank to Athens. (At this point the Reichsbank was working almost exclusively with looted gold.)

But Hahn’s first set of figures records shipments starting on February 4, 1943, and continuing until September 21, 1943. The amounts begin to decline in May. Hahn noted vaguely that the figures corresponded to shipment “lists” in Berlin and Vienna and that the gold had been “received” in Athens. There is no indication, however, as there is in the second set of figures, that the gold had been “dispatched” from Berlin to Athens. Consequently, there is no hint about the gold’s original source. In a draft version of Hahn’s report, a reader noticed the seeming discrepancy, circling the column of figures from February to September 1943 and writing “1944?” in the margin.

75

75

Hahn didn’t make that correction. The inconsistency, together with the general secrecy surrounding the sale of gold prior to November 18, 1943, gives rise to the suspicion that the first set of figures refers to gold owned by the Jews of Salonika. The deliveries of gold from the Reichsbank, which only commenced in earnest in November 1943, totaled 324,000 gold pounds and 5,112,570 gold francs. The amounts Hahn recorded between February and September of that year were significantly higher: 455,000 gold pounds and 9,340,290 gold francs.

76

According to Hahn’s final report, the Reichsbank dispatched, “all in all, some 24 million” reichsmarks’ worth of gold.

77

At the rate of 2.8 million reichsmarks per ton, the total would be equivalent to 8.6 tons. If one uses this standard for the period from February to September, German economists must have allocated at least twelve tons of gold during that period to prop up the drachma. This figure is nearly identical to the amount of gold plundered in Salonika, as estimated by Joseph Nehama. There can be little doubt that the Salonika gold and Hahn’s unidentified shipments are one and the same.

78

76

According to Hahn’s final report, the Reichsbank dispatched, “all in all, some 24 million” reichsmarks’ worth of gold.

77

At the rate of 2.8 million reichsmarks per ton, the total would be equivalent to 8.6 tons. If one uses this standard for the period from February to September, German economists must have allocated at least twelve tons of gold during that period to prop up the drachma. This figure is nearly identical to the amount of gold plundered in Salonika, as estimated by Joseph Nehama. There can be little doubt that the Salonika gold and Hahn’s unidentified shipments are one and the same.

78

Neubacher and Hahn’s intervention, using gold plundered from Jewish households, had the immediate effect of stabilizing the Greek currency.

Excerpt from Paul Hahn’s final report about his activities as Reichsbank commissioner in Greece, April 12, 1945. See translation on next page

.

.

The Reichsbank’s economists noted with satisfaction: “We were able to basically check the upward trend in prices.” On May 19, 1943, a gold pound still cost only 249,000 drachmas, rising to 380,000 as the intervention began. Except for a single short spike, the exchange rate held steady. Only in late August did the value of the gold pound exceed its previous high against the drachma, in October 1942.

79

In the interval, the Wehrmacht intendant for German-occupied Greece was able to report that the economic situation had “largely settled down” and that prices had been drastically reduced relative to those of late 1942. Simultaneously, Neubacher cut the Wehrmacht’s budget for expenditures by a third. But from September 21 to November 17, 1943, once the remainder of the gold plundered from Salonika’s Jews had been sold off and the proceeds spent by the Wehrmacht, the price of a gold pound rocketed from 474,000 to 1,900,000 drachmas. On November 24, after the first delivery of gold from the Reichsbank, the price went back down to 900,000 drachmas.

80

79

In the interval, the Wehrmacht intendant for German-occupied Greece was able to report that the economic situation had “largely settled down” and that prices had been drastically reduced relative to those of late 1942. Simultaneously, Neubacher cut the Wehrmacht’s budget for expenditures by a third. But from September 21 to November 17, 1943, once the remainder of the gold plundered from Salonika’s Jews had been sold off and the proceeds spent by the Wehrmacht, the price of a gold pound rocketed from 474,000 to 1,900,000 drachmas. On November 24, after the first delivery of gold from the Reichsbank, the price went back down to 900,000 drachmas.

80

The infusions of gold between February and September 1943 were included in Hahn’s balance sheet but not in the text of his final report. Neubacher suppressed them entirely from his memoirs and treated that period of his tenure in Greece with the utmost discretion. In late April 1943, Fritz Berger, a ministerial director in the Finance Ministry who apparently had not been informed about what was going on, addressed an urgent letter to the “Wehrmacht Finance Division, Greece.” In it, he complained that Neubacher had reduced Greek contributions to the occupation costs by more than 85 percent. That move, Berger objected, “would lead to a dead end” and force the Reich to pick up the extra costs. Three weeks later, the chief intendant to the military commander in southeastern Europe, who was well aware of the true situation, received a telephone call and noted: “The subject of the urgent letter has been rendered obsolete after telephone negotiations by the special emissary with the relevant Berlin offices.”

81

Clearly the Finance Ministry had been informed in the meantime about the rationale behind Neubacher’s temporary concern for the Greek treasury—and his top-secret strategy for making up the Wehrmacht shortfall with the gold from the Jews of Salonika. It is likely that Nazi officials discussed the strategy only orally. No written record exists. In any case, by July 15, 1943, Berger acknowledged that “all [the Wehrmacht’s] major needs have been met by emissary Neubacher, and the complaints registered in this regard were based on false suppositions and are therefore unjustified.”

82

81

Clearly the Finance Ministry had been informed in the meantime about the rationale behind Neubacher’s temporary concern for the Greek treasury—and his top-secret strategy for making up the Wehrmacht shortfall with the gold from the Jews of Salonika. It is likely that Nazi officials discussed the strategy only orally. No written record exists. In any case, by July 15, 1943, Berger acknowledged that “all [the Wehrmacht’s] major needs have been met by emissary Neubacher, and the complaints registered in this regard were based on false suppositions and are therefore unjustified.”

82

Neubacher met those needs by selling gold on the Athens exchange. In July 1943, an officer of the economics command in Athens observed: “Speculation had driven the price of the [gold] pound up to 540,000 drachmas. The fact alone that emissary Neubacher spent a short time in Athens drove it back down to 400,000. Through the sale of small amounts of gold, the price was later further reduced to 340,000 drachmas.”

83

That the price of gold fell with the mere arrival of Hitler’s special emissary shows how much influence he had on the Greek gold exchange in July 1943; there had already been nine interventions by that point. In many ways, Neubacher’s memoirs echo the story told by Paul Hahn, but with one crucial difference: Neubacher moved the gold transfers forward in time so that they would fall within the period of the official “gold campaign.”

84

83

That the price of gold fell with the mere arrival of Hitler’s special emissary shows how much influence he had on the Greek gold exchange in July 1943; there had already been nine interventions by that point. In many ways, Neubacher’s memoirs echo the story told by Paul Hahn, but with one crucial difference: Neubacher moved the gold transfers forward in time so that they would fall within the period of the official “gold campaign.”

84

German-Greek Silence

Other books

The Best Things in Death by Lenore Appelhans

Winter of the World by Ken Follett

Bellwether by Connie Willis

Hissy Fitz by Patrick Jennings

Bad Boy Billionaire: F#cking Jerk 3 by Tawny Taylor

The Crush by Sandra Brown

Shadow Zone by Iris Johansen, Roy Johansen

The Corpse in Oozak's Pond by Charlotte MacLeod

The Boss's Fake Fiancee by Inara Scott