Hitler's Beneficiaries: Plunder, Racial War, and the Nazi Welfare State (43 page)

Read Hitler's Beneficiaries: Plunder, Racial War, and the Nazi Welfare State Online

Authors: Götz Aly

BOOK: Hitler's Beneficiaries: Plunder, Racial War, and the Nazi Welfare State

10.55Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

In the war budget for 1942-43, taxes on German property owners accounted for 18 percent of domestic revenues. Contributions from occupied countries, bolstered by the proceeds from “de-Jewification,” accounted for a similar percentage of foreign revenues. Such additional sources of revenue allowed the regime to shift burdens from German taxpayers. They also allowed field commanders to slow the rapacious exploitation of occupied countries, such as Greece, while at the same time financing soldiers’ pay, military construction projects, and weapons purchases. At a precarious point in the war, the dispossession of European Jews brought significant resources into the German treasury, enabling the regime to avoid overtaxing its citizens. That encouraged stability within Germany and a willingness among the people of occupied lands to collaborate with the Reich, thereby lessening the fallout from Germany’s military defeats.

When German and non-German economists converted Jewish assets into war bonds, they did not formally violate prohibitions against dispossession enunciated in various national constitutions and the Hague Conventions. Ostensibly, they were merely transferring assets, making Jews into creditors of countries that were waging war or had been occupied. But the creditors were murdered in gas chambers. Whatever German financial specialists told themselves about the likely fate of Jews deported “for work details in the East,” they must have known that their unwilling creditors would never be seen again. They had a vested interest in genocide since they themselves benefited from the result. Comparing the concrete policies of “de-Jewification” in the vrious regions of Europe makes clear that dispossession did not necessarily have to go hand in hand with widespread elimination. In France, Romania, and Bulgaria, political considerations, the course of the war, and the willingness of national or local groups—or even individuals—to help those who were being persecuted sufficed to break the logic of genocide.

Historians who have investigated the legal and moral dimensions of the Aryanization campaigns have generally ignored the financial technique, introduced by Nazi Germany in 1936, of funding military aims by forcibly shifting private investments into government bonds. This scholarly blind spot is all too appropriate, as the Nazi regime was at pains to conceal the material benefits of its epic-scale larceny. During the war, reports about the compulsory conversion of Jewish assets into war bonds were forbidden, and concrete figures about the proceeds earned were kept secret. Instead, the persecution of Jews was depicted in Nazi propaganda as a purely ideological issue. The defenseless victims of a mass campaign of murderous thievery were treated as enemies whose lives had no value whatsoever. In 1943 the Wehrmacht High Command prepared a list of nineteen political and military problems that could potentially cause unrest among soldiers. Officers were supposed to be able to respond to these questions with consistent answers. The list contained the query “Have we gone too far with the Jewish question?” The answer read: “Wrong question! Basic principle of National Socialism and its view of the world—no discussion!”

2

But scholars should not confuse Nazi propaganda with historical fact.

2

But scholars should not confuse Nazi propaganda with historical fact.

AFTER THE WAR, courts throughout Europe took up the matter of the reparations owed by the East and West German states to the victims of Nazi aggression. On numerous occasions, legal representatives of both the Federal Republic and the German Democratic Republic argued that in those lands occupied by the Reich the dispossession of Europe’s Jews was the work not of the Nazi authorities but rather of the governments and administrators of the occupied countries themselves.

There is a grain of truth to this argument. As the preceding chapters have shown, most of the material goods stolen from Jews changed hands in the countries and regions where they had been looted. The expropriations themselves were usually carried out by officials of the occupied state. Citing these facts, postwar German reparations courts dismissed tens of thousands of lawsuits originating outside the boundaries of the Third Reich.

The reality, of course, is far more damning. The present volume has demonstrated that the proceeds from the sale of purloined Jewish assets almost always found their way, directly or indirectly, into the German war chest. The Reich and its citizens also benefited from the increased availability of capital, real estate, and goods ranging from precious stones and jewels all the way down to the cheap wares sold at flea markets. The dispossession of the Jews also stabilized the economies and calmed the political atmosphere in occupied countries, greatly simplifying the task of the Wehrmacht. Goods sold off at less than their actual worth provided an indirect subsidy to both German and foreign buyers.

The exploitation of the Jews was attractive to politicians in occupied countries such as Greece, France, and, late in the war, Hungary. The occupation costs demanded by Germany were massive and, ultimately, ruinous. But German occupiers also offered the countries they controlled the possibility of easing their burden by jointly robbing and then eradicating a convenient scapegoat—Jews. The connection here has ofrectly en overlooked, both in the recent literature on the Aryanization campaigns and in the detailed reports of national commissions of historians called on to investigate the dispossession of European Jews. It was obvious, however, to observers at the time. On August 3, 1944, the

Neue Zürcher Zeitung

in Switzerland wrote: “With the Aryanization of Jewish businesses [in Hungary], the purchase price set by the government is to be paid immediately in cash. This shows that the operation, as was the case previously in Germany itself, possesses a certain fiscal significance (the easing of wartime finances).”

3

Neue Zürcher Zeitung

in Switzerland wrote: “With the Aryanization of Jewish businesses [in Hungary], the purchase price set by the government is to be paid immediately in cash. This shows that the operation, as was the case previously in Germany itself, possesses a certain fiscal significance (the easing of wartime finances).”

3

At present only rough estimates of the total amount of Jewish assets Germany looted and liquidated during World War II are available. The economist Helen B. Junz has developed an extremely useful methodology, which she describes in her book

Where Did All the Money Go? The Pre-Nazi-Era Wealth of European Jewry

. A more exact calculation, using her formula, is still needed. Existing data on Aryanization in some European countries should also be revisited and expanded in light of the results of the present investigation. Until that time, however, it is safe to say that a total of between 15 and 20 billion reichsmarks in assets from the households of European Jews were liquidated, and the money earned was diverted to pay German war costs.

Where Did All the Money Go? The Pre-Nazi-Era Wealth of European Jewry

. A more exact calculation, using her formula, is still needed. Existing data on Aryanization in some European countries should also be revisited and expanded in light of the results of the present investigation. Until that time, however, it is safe to say that a total of between 15 and 20 billion reichsmarks in assets from the households of European Jews were liquidated, and the money earned was diverted to pay German war costs.

Since sums of money, large and small, from liquidated Jewish assets were used to pay soldiers’ wages throughout occupied Europe, any goods acquired by those troops—from butter sent home to Cologne to sleeveless sweaters purchased in Antwerp and even cigarettes—were underwritten to a greater or lesser degree by the estates of dispossessed and murdered Jews. The same is true for official deliveries of food from occupied countries and Germany’s allies to the homeland. They, too, were paid for with money extracted from the exploitation of Jewish assets in France, Holland, Romania, Serbia, Poland, and elsewhere. While butter for German families may have come from Switzerland, it was paid for, at least in part, by gold and currency confiscated in the death camps. Adding to these figures was the use of Jewish slave laborers: from 1940 onward 50 percent of their wages flowed into the state treasury, where it made up a small percentage of the funds needed for support payments to German women and children, as well as for arms purchases. The system was arranged to benefit all Germans. Ultimately every member of the master race—not just Nazi Party functionaries but 95 percent of the German populace—profited in the form of money in their pockets or food on their plates that was paid for by looted foreign currency and gold. Victims of bombing raids wore the clothing and slept in the beds of those who had been murdered. The beneficiaries could breathe easier, thankful that they had survived another day, and no doubt thankful also that the state and the party had been so quick to come to their aid.

The Holocaust will never be properly understood until it is seen as the most single-mindedly pursued campaign of murderous larceny in modern history.

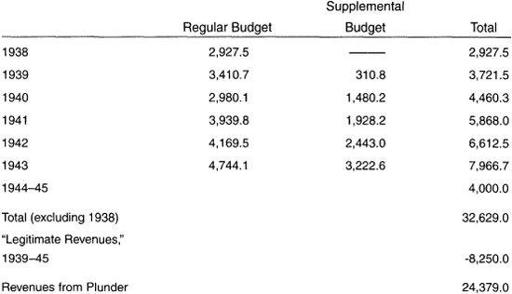

War Revenues, 1939-45

The preceding chapters have presented a great number of specific budgetary figures: proceeds from various expropriation campaigns, account balances, percentages, and so on. The current chapter focuses instead on the total sums involved. The following pages sketch out the structure of Germany’s wartime revenues with an eye toward answering two questions: First, how did the portion of operating revenues that came from German citizens compare with that extracted from occupied Europe and the Reich’s allies? And seconhow was the burden of costs borne by Germany itself divided among the various classes of taxpayers?

The table of estimated war contributions from other countries in Europe, below, is based on four documents drawn up relatively late in the war by civil servants in the Reichsbank and the Finance Ministry. These documents provided the most significant figures, which have been expanded with information from other sources and estimates by the author.

Because Germany had no intention of paying off clearing debts owed to occupied (and allied) countries—balancing them, instead, with fictional external occupation costs—Göring’s advisers felt no compunction about entering these sums as revenues. This trick produced an accurate accounting only when the Reich immediately spent the clearing “advances” on goods and services in the countries in question. Often it didn’t. Moreover, those responsible for the Reich budget made no distinction between contributions from subjugated nations and from allied countries, recording all revenues as payments against (greatly exaggerated) occupation costs.

Wherever there are competing figures, the more conservative one has been used in the tables below. It’s important to note that the numbers themselves represent only a part of the wartime damage the Third Reich inflicted on occupied Europe and its own dependent states.

4

4

The “Donner Factor” in the second-to-last line of table 5, requires explanation. On closer examination, the figures for the Soviet Union and for “Captured Property” appear much too low. Otto Donner, Göring’s financial adviser, thought as much in 1944, and to correct the figures, he suggested adding 9 to 18 percent to the total to cover “amounts that aren’t statistically measurable.” In light of what has been described in the preceding chapters, a Donner factor of 15 percent has been added for goods and services that cannot be documented in German-dominated Europe. Even this figure may be too low.

Table 5: Revenues from Occupied Countries and Dependent States, 1939-45 (in Billions of Reichsmarks)

The total sum of over 131 billion reichsmarks is about nine times more than what the German Reich received in regular tax revenues in the last year before World War II. But this figure represents only a part, albeit a large one, of the external revenues Germany extracted via plunder between 1939 and 1945. Wage taxes automatically paid by slave laborers, their contributions to the social welfare system, and the de facto subsidies their labor provided to German agriculture should be added to the total. General administrative revenues extracted from the compulsory savings accounts of Eastern European workers and sham remittances of wages to family members drive the final reckoning even higher.

5

These, too, were budgetary resources acquired at the cost of foreign countries.

5

These, too, were budgetary resources acquired at the cost of foreign countries.

There are no documents available that break down the exact sources of general administrative revenues. A rough estimate, however, can be made based on a balance sheet drawn up by the statistics office of the Finance Ministry in 1944. This document includes contributions from the General Government of Poland and the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, which have to be subtracted, since they have already been listed in the above table. (Nazi statisticians considered the Polish and Czech rritories to be part of the Reich.) Increased profits earned by the Reichs-post, the Reichsbahn (German rail), and the Reichsbank, which have to be considered internal sources of revenue, should also be excluded.

6

Nor can wartime contributions paid by local states and towns within Germany be treated as additional sources of wartime revenues. Although these contributions—totaling slightly more than 10 billion reichsmarks—could not be spent on local projects, there is no evidence that the shift of funds to the Reich treasury exerted a negative influence on public opinion.

6

Nor can wartime contributions paid by local states and towns within Germany be treated as additional sources of wartime revenues. Although these contributions—totaling slightly more than 10 billion reichsmarks—could not be spent on local projects, there is no evidence that the shift of funds to the Reich treasury exerted a negative influence on public opinion.

Subtracting these sums from general administrative revenues yields an amount of money that statisticians within the Finance Ministry recorded under the nebulous category “Remaining Revenues.” The question arises as to how much of this money was earned by relatively honest means. Table 6 gives an estimate of general revenues, including a separate figure for those earned by “legitimate” means. This latter sum was arrived at by using figures from the “Remaining Revenues” column in the regular Reich budgets for 1938 and 1939. Because they include the proceeds from the Aryanization campaign, the atonement payments, and the occupation of Austria, Bohemia and Moravia, and parts of Poland by German troops, these figures are relatively high. Nonetheless some 1.5 billion reichsmarks per year came from sources that can be considered legitimate. Assuming the amount remained constant over five and a half years of war, around 8.25 billion reichsmarks of the money entered under the category “General Administrative Revenues/Remaining Revenues” came from regular domestic sources. The rest constitutes external revenues—money earned by plundering the citizens of foreign states. The following estimate for 1944-45 has been kept conservative—possibly too conservative—to reflect Germany’s territorial losses in the final phase of World War II.

Other books

Giving Up the Ghost by Marilyn Levinson

Schrodinger's Cat Trilogy by Robert A. Wilson

Policia Sideral by George H. White

Sins Out of School by Jeanne M. Dams

A Man of Honor by Ethan Radcliff

La Bella Isabella by Raven McAllan

Call of the Dark (Dark Paranormal Steamy Monster Encounter) by Cassia Dureza

The Hollow Places by Dean Edwards

Ice Dreams Part 2 by Melissa Johns

Sinful's Desire by Jana Leigh, Gracie Meadows