Hitler's Jet Plane (13 page)

Read Hitler's Jet Plane Online

Authors: Mano Ziegler

Tags: #Engineering & Transportation, #Engineering, #History, #Military, #Aviation, #World War II, #Military Science

On 20 and 21 May 1944 the Allies destroyed the German synthetic fuel plants and attacked Berlin with an air fleet consisting of 1,500 bombers and 1,000 fighters. On 22 May the Soviet Army began its summer offensive under an umbrella of 4,000 aircraft.

After the violent verbal exchange between Hitler and Generalfeldmarschall Milch at the Berghof on 24 May 1944, the future of the Me 262 as a lame-duck bomber seemed certain. On the 29th, Oberst Gollob, Galland’s staff officer with responsibility for the Me 262 fighter, was relieved of the portfolio by Goering who transferred it to General der Kampfflieger, Generalleutnant Peltz. At about the same time, Oberst Petersen advised Milch that the whole field of aircraft production, which was until then Milch’s responsibility, was being transferred to the newly appointed Chief of the Fighter Staff, Karl-Otto Saur, Speer’s deputy. That signalled the end of Milch’s role as Goering’s Plenipotentiary which he had held since the summer of 1941.

On 7 June 1944, the day following the Normandy landings, Hitler ordered an increase in Me 262 and Do 335 production. During the Invasion, aircraft of the Allied air forces flew 14,700 missions compared with 319 of the Luftwaffe. On 19 June, Milch found out that he was to be relieved of his office. His request to resign as Secretary of State and Minister for Aircraft Production was approved by Hitler with the result that the office devolved upon Speer and Saur. On 25 June Hitler demanded a greater effort in the fight to reduce Allied air superiority and asked Saur how many fighters could be turned out each month if production work on the He 177 bomber were suspended. Saur told him about a thousand. On 27 June Goering ordered a halt to bomber production. When General Köller protested, Goering told him, ‘It is the will of the Führer that only fighters are to be built from now on.’ On two occasions, immediately after the attempt on Hitler’s life on 20 July 1944 and again on 30 August, General Kreipe solicited Hitler’s agreement for the exclusive deployment of the Me 262 as a fighter. Hitler made a brusque refusal each time. At the end of August Hitler circulated throughout the Luftwaffe a Führer-edict which every officer was obliged to sign. This order read: ‘With immediate effect I forbid anybody to speak to me about the Me 262 jet aircraft in any other connection or any other role than as a fast or Blitzbomber.’

Nine months for possible Me 262 fighter operations had been lost up to the time when Kommando Nowotny was formed. Without question these nine months were decisive for the seizure of air supremacy over the Reich by the Allies, the precondition for the total defeat of Hitler’s Germany. Hitler may have sensed that for himself when he suddenly began to demand ‘Fighters! Fighters! Only fighters!’

5

Hitler’s resistance crumbled further in mid-September 1944. Major Walther Dahl had set up IV

Sturmgruppe

within JG3 Udet in May 1944. Once operational in September, after only two days this piston-engined fighter group initially produced astounding successes pitted as they were against a numerically superior enemy force of bombers and fighters. This led to corresponding Allied countermeasures such that the unit was hard hit by a sudden reversal of fortune on the third day. In his remarkable book

Rammjäger

Dahl described it thus: with Dahl leading his Sturmgruppe on 11 September 1944, they shot down 170 enemy aircraft (95 bombers, 75 fighters) for only 3 German losses. On 12 September the tally was 100 enemy aircraft (87 bombers, 13 fighters) for 13 German losses. On 13 September the Allied bomber formation lost 24 aircraft (7 bombers, 17 fighters) for the loss of 36 German aircraft. The reversal was caused by the Allied air force having strengthened the fighter escort substantially. On account of this adverse swing in the fortunes of his unit, Major Dahl was summoned at once over Goering’s head to Hitler’s HQ. In his book he records:

I arrived at Führer HQ Wolfschanze in East Prussia and was taken to the so-called situations room where I waited for Hitler... suddenly I saw a figure entering the bunker with a tired walk, bent as if carrying a heavy burden. It was Hitler!

The Luftwaffe ADC, Oberst von Below, introduced me and I reported myself. Hitler offered me his hand and said warmly, ‘I am pleased to see you here. I have already heard much about you and the efforts of the brave men of your squadron. Your

Sturmgruppen

(fighter assault groups) have made a decisive contribution and I am proud to have such pilots in the Luftwaffe.’ With a gesture he invited me to take an armchair. I sat directly opposite him. He came at once to our three engagements of 11 to 13 September, the actual reason for my presence. I had to describe exactly the course of each air-battle and especially that of ‘the black 13 September’. During the session of question and answer with Hitler, the no. 1 problem of the Luftwaffe, the Me 262, was constantly at the back of my mind. Somehow I had to bring the topic of conversation round to this theme despite the Führer-edict of the month before.

As Hitler began speaking about our heavy losses of 13 September, he attributed them to the numerical superiority of the bombers. I saw my chance. ‘The enemy fighters are our greatest danger in the air,’ I said, ‘and only fast, very fast, aircraft can win us the opportunity to strip away from formations the enemy fighter cover so that the bombers can be attacked unmolested.’ Tensely I waited for his reaction. He gave me a searching look and then his gruff voice replied, ‘You mean the Me 262. Say what you want to.’ I knew that my opinion contradicted his own but I attempted to convince Hitler by argument. During the resulting discussion, Hitler astonished me with his precise knowledge of technical details. At the end of our talk, which lasted almost three hours, I had the feeling that my opinion was not without its echo. Some time later the order came down that a proportion of Me 262 was to be re-scheduled for the fighter arm.

Galland was overjoyed. To some extent he now had a free hand and nominated as commander of the combined Kommando 262 Thierfelder – Wegmann the best available man, Austrian-born Major Walter Nowotny, with 256 kills to his credit the second most successful fighter pilot after Erich Hartmann. Besides being a proven and thoroughly capable wing leader, he knew how to nurse inexperienced young pilots through their first combat missions. In view of the sizeable contingent of pilots in Kommando Nowotny fresh from training school, that seemed to Galland a point of no small importance.

In his letter to me dated 26 January 1977 responding to my request for information, Adolf Galland recounted the inside story of many events related in this book, principally the setting-up of the Kommando Nowotny, and its last day of operations. I reproduce here the pertinent abstract from the letter because it shows how the formation of Kommando Nowotny coincides closely with the political manoeuvring referred to earlier in this chapter. In September 1944 Galland had received from Goering the order:

. . . to set up forthwith an operational Kommando from the two manufacturer’s test units, and locate it on the Western Front. Apparently this was done on Himmler’s advice that it was a simple way of providing evidence in the form of aerial combat victories that the Me 262 was an outstanding fighter aircraft. My objection that the development was too rapid and that this unit would be better defending the Reich from within was unsuccessful. I appointed Major Nowotny commander of the unit and told him to operate from Achmer near Rheine. Here, under the the most difficult circumstances, aided by a constant fighter umbrella to protect the runways at Achmer and Hesepe, he achieved good results but also sustained losses. I mention particularly a large number of losses attributable to technical faults and errors for which the ground personnel were partially responsible. On the day when he destroyed a Mustang and was himself shot down after a turbine failure, I was an onlooker. By telephone I ordered the withdrawal to Brandenburg-Briest and sent the pilots to Lechfeld for further training. It was from this unit, however, that the best jet Group, III/JG7, came into being . . .’

Professor Willy Messerschmitt (1898 – 1978), designer of the Me 262.

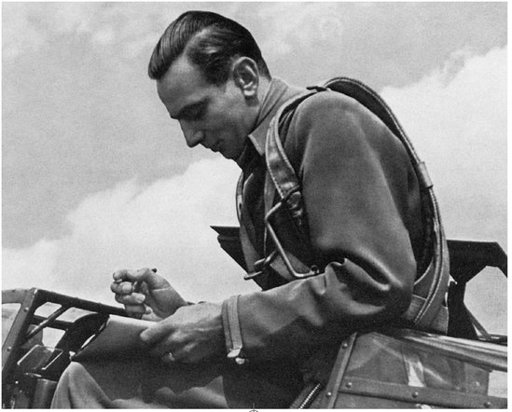

Flugkapitän Fritz Wendel, chief test pilot, Messerschmitt AG Augsburg.

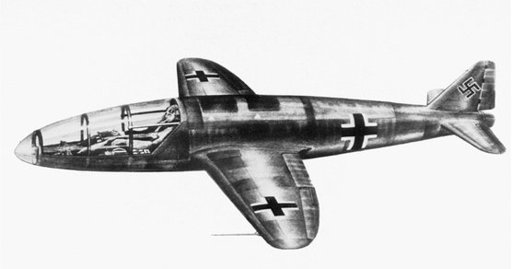

A montage depicting two Me 262A-1a fighters. The nearer aircraft, works number 110522, was flown by Fritz Wendel at Lechfeld as part of III/EJG2 and later with Nowotny’s Kommando.

An Me 262 in England after the war.

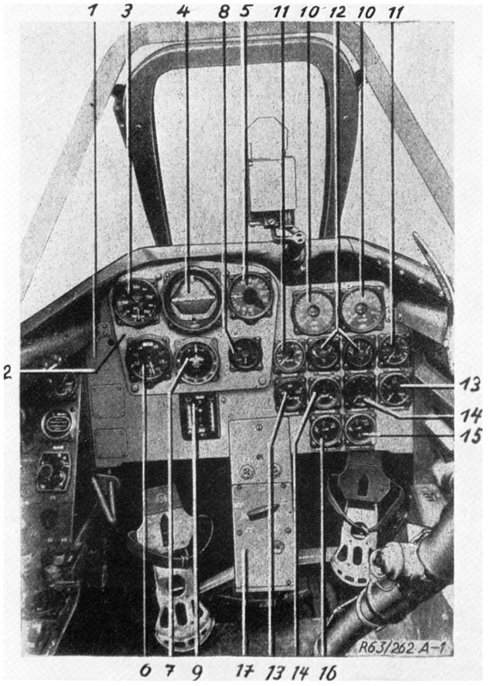

The cockpit of the Me 262: (1) Instrument panel (2) Blind flying equipment (Ed: NB-perhaps he means panel far left. Tr.) (3) Speedometer (4) Artificial horizon (5) Variometer (6) Altimeter (7) Main daughter compass (8) AFN2 (9) SZKK2 (10) Revolutions indicator (11) Gas pressure gauge (12) Gas temperature indicators (13) Pressure gauge (injection) (14) Pressure gauge (lubricant) (15) Fuel gauge (forward tanks) (16) Fuel gauge (rear tanks) (17) ZSK 244A (only fitted to aircraft on Blitzbomber operations).