Holy Sh*t: A Brief History of Swearing (7 page)

Read Holy Sh*t: A Brief History of Swearing Online

Authors: Melissa Mohr

Tags: #History, #Social History, #Language Arts & Disciplines, #Linguistics, #General

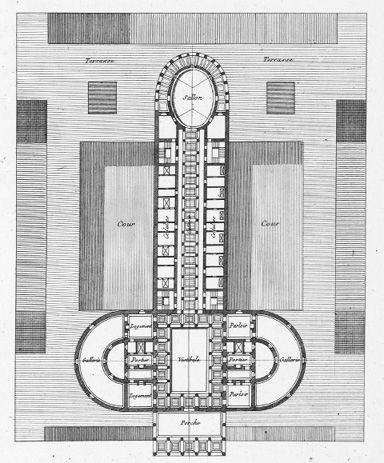

The Forum of Augustus, completed ca. AD 40. Can you find the phallus?

Walking around in ancient Rome, one saw a lot of penises. There were erect penises sculpted, painted, and scratched over door frames, on chariot wheels, in gardens, on the borders of fields, in elaborate murals in reception rooms of fancy villas, hung around the necks of prepubescent boys.

Even the Forum of Augustus

, the center of Roman political and military life, was designed in the shape of an erection. Some scholars argue that it is an example of

architecture parlante

—a building whose form speaks to its purpose. The forum was where military triumphs were celebrated, where law cases were argued, where boys came to put aside their childish clothing and assume the

toga virilis

, the garment that marked them out as full Roman citizens, as men. Something that today we see only in private was displayed prominently in public in ancient Rome.

This is another example of “speaking architecture,” the Oikema, designed by Claude-Nicholas Ledoux in the eighteenth century. Like the Roman Forum, it was to serve as a place of masculine initiation—it was to be a brothel. In Ledoux’s vision, the calming, classical style of the building, combined with some good instruction, would teach the young men inside to subjugate their sexual urges and become productive citizens of France. It was never built.

Most cultures—including ancient Rome’s and our own—dictate that whatever parts of the body should be concealed in clothing must also be concealed in language. Obscenities arise from the body parts and actions that a culture deems unacceptable for public display. Latin captures this link between the body and language by referring to obscene words as

nuda verba

—“naked words.” These words represent the thing itself, without the linguistic drapery of euphemism or circumlocution.

Given the prevalence of the public penis, and the link between concealment and obscenity, one would expect that Latin words for the penis would

not

be obscene. If you can

see

penises everywhere in public, you should be able to

say

the word for them in public. But actually, Latin words for the penis

are

obscene.

Mentula

(penis) was quite obscene, and

verpa

—a penis with its foreskin pulled back, hence erect or circumcised—was even worse. Even the word

penis

itself was offensive in Latin, though not as shocking as the two primary obscenities,

mentula

and

verpa

.

This dichotomy between what was seen and what could be said developed because in Rome, obscenity also had religious aspects.

According to Freud

, taboos have two contradictory directions, at least in the “traditional” societies popular with anthropologists of the early twentieth century. Taboo things are unclean and forbidden, but they are also sacred and consecrated. In ancient Rome, the genitalia were

verecunda

(parts of modesty) and

pudenda

(parts of

shame), but they were also

verenda

(parts of respect) and

veretrum

(parts of awe, with a healthy dose of fear). Modern English-speaking societies have lost the latter side of the binary—for us the genitals are shameful, but they inspire no religious respect.

As we’ve seen, one meaning of the Latin

obscenus

was “of ill omen,” signifying

things that would taint a religious rite

and make it fail. This category mostly included sexual acts and language—a vestal virgin not being quite virgin enough, a priest not abstaining from sex for long enough before a ceremony, insulting the gods with bad words. But this held true for only certain kinds of religious rites. Other kinds actually relied on obscenity for their success. The obscene had its own gods and goddesses, its own place in the smooth running of nature and the Roman state. We’ve already met the garden god Priapus, with his huge, perpetually erect phallus; Pan was the god of woodland groves and shepherds, with the hindquarters of a goat and his own large, often erect penis.

There was also the mysterious Mutunus Tutunus

, who may have been nothing

but

a giant erect penis, statues of whom brides had to sit on as part of the wedding ceremony. The erect penis symbolized, and in some sense was supposed to guarantee, fertility.

Obscene language, which represents the genitalia and sex so directly, was likewise used in ceremonies to promote fertility. Uttering these ordinarily taboo words at a wedding, for example, was thought to channel the procreative power of the things to which they referred, ensuring the fertility of the marriage.

Wedding guests would sing fescennine songs

, full of ribaldry and teasing. Unfortunately, no examples of these survive, but you can get a flavor from

an epithalamium

, a poem written in honor of a wedding, by Catullus, in which the poet urges the groom to give up his smooth boys now that he is about to be married, and advises the bride to deny her husband nothing (a common euphemism for oral sex in Latin) lest he start to seek his pleasures elsewhere. Obscenity was also an important part of festivals such as the

ludi florales

, the games of Flora, the goddess of spring. At the end of these games, prostitutes danced naked while

the crowd shouted obscenities to ensure the fertility of the coming season.

Obscene words were thought to be magical

, with the power to affect the world. If you wanted a marriage to produce children, or spring to come with healthy crops and young animals,

nuda verba

could help to bring it about.

Rome did not just associate the genitalia with fertility, however. The penis was also a symbol of threatening power. As we have seen, Roman culture thought of sex in terms of domination—the active male penetrates “lesser” creatures, whether women, boys, or passive men, defining himself as a “real man” and as a citizen. This power of the penis could be transferred to different areas.

Bullae

, the necklaces containing phallus-shaped

fascini

, were thought to shield their wearers from the evil eye—they had what is called apotropaic (from the Greek meaning “to ward off”) power. Songs containing obscenities could, in the right context, also protect people from evil forces. They were sung when someone’s good fortune was likely to attract

invidia

, envy or ill will. They offered protection in two ways—the obscenities themselves contained the power to ward off evil, and the songs’ mockery took their subjects down a peg or two, to a level where they no longer invited

invidia

.

Victorious generals were serenaded

with fescennine songs—their moment of triumph was also a moment of great weakness.

When Julius Caesar returned to Rome

in 46

BC

, for example, he was publicly celebrated for vanquishing the Gauls and publicly mocked for being the

cinaedus

of Nicomedes, king of Bithynia, many years earlier. One verse ran:

All the Gauls did Caesar vanquish, Nicomedes vanquished him;

Lo! now Caesar rides in triumph, victor over all the Gauls,

Nicomedes does not triumph, who subdued the conqueror.

Some verses were even more specific

, calling Nicomedes Caesar’s

pedicator

(butt fucker). The obscenity and mockery of these verses were thought to protect Caesar at this vulnerable moment when hundreds, even thousands of people might be watching him with envy.

Obscene words were also involved in Roman cursing. Today

cursing

is often used to mean obscene language (

does the government still have “good reason

to regulate cursing and nudity on broadcast television?” the

New York Times

asked recently). But

curse

originally had a much narrower definition, referring to language that wished ill on someone and called on a deity to make it happen. In English, our most familiar curses are of the form “(May) God damn you!” and “Go to hell!” Words such as

fuck

are curses in the loose sense of the term, but “Fuck you!” might be considered a curse according to its narrower meaning as well.

As Lenny Bruce supposedly noted

, it makes little sense to tell someone off in this way: “What’s the worst thing you can say to anybody? ‘Fuck you, Mister.’ It’s really weird, because if I really wanted to hurt you I should say ‘Unfuck you, Mister.’ Because ‘Fuck you’ is really

nice

!” Why wish something pleasurable on the person you are trying verbally to abuse? Some theories hold that “Fuck you!” is equivalent to “Go fuck yourself!” and that the impossibility furnishes the insult. It takes two to have sex, masturbation isn’t as fun—so there! Other theories hold that the phrase is a threat: “(I’ll) fuck you,” our equivalent to

irrumabo vos

. The phrase makes the most sense, however, when considered as a curse formula, with

fuck

simply replacing the

damn

in “Damn you!” A powerfully taboo body-related word substitutes for the weakly taboo religious one so that the curse can retain its impact.

Roman curses were much more elaborate

and ritualistic. They were scratched on thin pieces of lead and tin, tightly folded up, pierced with a nail, and cast into wells or tombs so that they could reach the gods of the underworld, whose aid they invoked. They were called

defixiones

—binding spells—because they were supposed to restrain or bind the person mentioned in the curse. A typical example comes from a tablet near Rome:

Malchio son/slave of Nikon

: his eyes, hands, fingers, arms, nails, hair, head, feet, thigh, belly, buttocks, navel, chest, nipples, neck, mouth, cheeks, teeth, lips, chin, eyes, forehead, eyebrows, shoulder-blades, shoulders, sinews, guts, marrow [?], belly, cock [

mentula

], leg, trade, income, health, I do curse [“bind,”

deficio

] in this tablet.

Whatever Malchio had done, it made somebody really angry.

Bind

at first might seem an ineffectual verb with which to curse, but the idea is that such restraint renders powerless the things bound.

Gladiators and charioteers

, thieves, and unfaithful partners of both sexes were common targets of

defixiones

.

On the back of Malchio’s tablet

there is a curse directed at Rufa Publica (Rufa the “public woman,” the prostitute) that binds her body parts in a similar fashion, including her nipples (

mamillae

) and

cunnus

. Perhaps Rufa and Malchio had gotten a thing going and her cuckolded lover cursed them both. Or perhaps the curser simply wanted to save some money, gratifying two unrelated grudges with one curse tablet. In any case, the use of obscene words in

defixiones

seems to have had no particular significance for the working of the curse. A word such as

mentula

was employed simply as the

vox propria

, the most direct word for a thing, on a par with

dentes

(teeth) or

pedes

(feet). The concept of cursing, though, is closely connected to obscenity. The

defixiones

were, like some Roman

obscenitas

, a religious language—they called on the gods to effect the curser’s wishes. In modern English,

cursing

has mostly lost its religious implications, and its meaning has changed to indicate the taboo words for body parts and actions that were a feature of Latin cursing but were not of its essence.

How We Recognize Latin Obscenity

How can we be sure that the words we’ve been talking about are actually obscene? Latin is a dead language. No one has a firsthand sense of what was sayable and what wasn’t. How do scholars know, for example, that

cunnus

was a very, very bad word, while

meio

was not obscene at all?

The first tool linguists use is the hierarchy of genres

. Latin literature observes a strict linguistic decorum, with certain kinds of words considered appropriate for particular genres. From most salacious to least, the scale goes:

1. Graffito and epigram

2. Satire

3. Oratory and elegy

4. Epic

The most taboo words

are found in the graffiti that were scratched everywhere in the Roman Empire—inside and outside houses, on columns in the Forum, in the public latrines, on gravestones, on sling bullets fired at enemies. If Pompeii is representative, and scholars generally agree that it is, most Roman cities would have been covered in scrawl. Occasionally the graffiti “artists” themselves took notice of this abundance, as one did in the amphitheater in Rome: “

Oh wall, I am amazed

that you have not fallen down since you support the loathsome scribblings of so many writers.” Walls were often the most convenient place to put any “loathsome scribblings” you might want to get off your chest. Romans didn’t have paper; vellum, made of animal skin, was extremely expensive; and wax tablets were neither permanent nor always very handy. Merchants wrote their prices on the walls of their shop and figured sums there. Advertisements for goods and services—including those offered by prostitutes—were inscribed on buildings across Pompeii. Election notices can also still be seen there, in which various groups of tradesmen recommended various candidates for office: “

The goldsmiths unanimously urge

the election of Gaius Cuspius Pansa as aedile.”

*

Such notices were so ubiquitous that they attracted their share of parody: “

Dickhead recommends

Lollius” (

Lollius

…

verpus rogat

).