Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow (17 page)

Read Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow Online

Authors: Yuval Noah Harari

Hence if this discussion has left you confused and perplexed, you are in very good company. The best scientists too are a long way from deciphering the enigma of mind and consciousness. One of the wonderful things about science is that when scientists don’t know something, they can try out all kinds of theories and conjunctures, but in the end they can just admit their ignorance.

The Equation of Life

Scientists don’t know how a collection of electric brain signals creates subjective experiences. Even more crucially, they don’t know what could be the evolutionary benefit of such a phenomenon. It is the greatest lacuna in our understanding of life. Humans have feet, because for millions of generations feet enabled our ancestors to chase rabbits and escape lions. Humans have eyes, because for countless millennia eyes enabled our forebears to see whither the rabbit was heading and whence the lion was coming. But why do humans have subjective experiences of hunger and fear?

Not long ago, biologists gave a very simple answer. Subjective experiences are essential for our survival, because if we didn’t feel hunger or fear we would not have bothered to chase rabbits and flee lions. Upon seeing a lion, why did a man flee? Well, he was frightened, so he ran away. Subjective experiences explained human actions. Yet today scientists provide a much more detailed explanation. When a man sees a lion, electric signals move from the eye to the brain. The incoming signals stimulate certain neurons, which react by firing off more signals. These stimulate other neurons down the line, which fire in their turn. If enough of the right neurons fire at a sufficiently rapid rate, commands are sent to the adrenal glands to flood the body with adrenaline, the heart is instructed to beat faster, while neurons in the motor centre send signals down to the leg muscles, which begin to stretch and contract, and the man runs away from the lion.

Ironically, the better we map this process, the

harder

it becomes to explain conscious feelings. The better we understand the brain, the more redundant the mind seems. If the entire system works by electric signals passing from here to there, why the hell do we also need to

feel

fear? If a chain of electrochemical reactions leads all the way from the nerve cells in the eye to the movements of leg muscles, why add subjective experiences to this chain? What do they do? Countless domino pieces can fall one after the other without any need of subjective experiences. Why do neurons need feelings in order to stimulate one another, or in order to tell the adrenal gland to start pumping? Indeed, 99 per cent of bodily activities, including muscle movement and hormonal secretions, take place without any need of conscious feelings. So why do the neurons, muscles and glands need such feelings in the remaining 1 per cent of cases?

You might argue that we need a mind because the mind stores memories, makes plans and autonomously sparks completely new images and ideas. It doesn’t just respond to outside stimuli. For example, when a man sees a lion, he doesn’t react automatically to the sight of the predator. He remembers that a year ago a lion ate his aunt. He imagines how he would feel if a lion tore him to pieces. He contemplates the fate of his orphaned children. That’s why he flees. Indeed, many chain reactions begin with the mind’s own initiative rather than with any immediate external stimulus. Thus a memory of some prior lion attack might spontaneously pop up in a man’s mind, setting him thinking about the danger posed by lions. He then gets all the tribespeople together and they brainstorm novel methods for scaring lions away.

But wait a moment. What are all these memories, imaginations and thoughts? Where do they exist? According to current biological theories, our memories, imaginations and thoughts don’t exist in some higher immaterial field. Rather, they too are avalanches of electric signals fired by billions of neurons. Hence even when we figure in memories, imaginations and thoughts, we are still left with a series of electrochemical reactions that pass through billions of neurons, ending with the activity of adrenal glands and leg muscles.

Is there even a single step on this long and twisting journey where, between the action of one neuron and the reaction of the next, the mind intervenes and decides whether the second neuron should fire or not? Is there any material movement, of even a single electron, that is caused by the subjective experience of fear rather than by the prior movement of some other particle? If there is no such movement – and if every electron moves because another electron moved earlier – why do we need to experience fear? We have no clue.

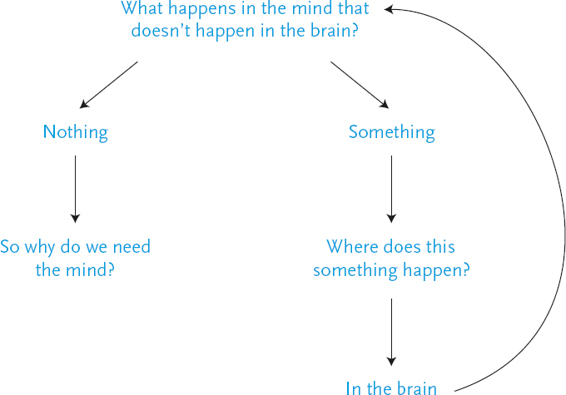

Philosophers have encapsulated this riddle in a trick question: what happens in the mind that doesn’t happen in the brain? If nothing happens in the mind except what happens in our massive network of neurons – then why do we need the mind? If something does indeed happen in the mind over and above what happens in the neural network – where the hell does it happen? Suppose I ask you what Homer Simpson thought about Bill Clinton and the Monica Lewinsky scandal. You have probably never thought about this before, so your mind now needs to fuse two previously unrelated memories, perhaps conjuring up an image of Homer drinking beer while watching the president give his ‘I did not have sexual relations with that woman’ speech. Where does this fusion take place?

Some brain scientists argue that it happens in the ‘global workspace’ created by the interaction of many neurons.

4

Yet the word ‘workspace’ is just a metaphor. What is the reality behind the metaphor? Where do the different pieces of information actually meet and fuse? According to current theories, it certainly doesn’t take place in some Platonic fifth dimension. Rather, it takes place, say, where two previously unconnected neurons suddenly start firing signals to one another. A new synapse is formed between the Bill Clinton neuron and the Homer Simpson neuron. But if so, why do we need the conscious experience of memory over and above the physical event of the two neurons connecting?

We can pose the same riddle in mathematical terms. Present-day dogma holds that organisms are algorithms, and that algorithms

can be represented in mathematical formulas. You can use numbers and mathematical symbols to write the series of steps a vending machine takes to prepare a cup of tea, and the series of steps a brain takes when it is alarmed by the approach of a lion. If so, and if conscious experiences fulfil some important function, they must have a mathematical representation. For they are an essential part of the algorithm. When we write the fear algorithm, and break ‘fear’ down into a series of precise calculations, we should be able to point out: ‘Here, step number ninety-three in the calculation process – this is the subjective experience of fear!’ But is there any algorithm in the huge realm of mathematics that contains a subjective experience? So far, we don’t know of any such algorithm. Despite the vast knowledge we have gained in the fields of mathematics and computer science, none of the data-processing systems we have created needs subjective experiences in order to function, and none feels pain, pleasure, anger or love.

5

Maybe we need subjective experiences in order to think about ourselves? An animal wandering the savannah and calculating its chances of survival and reproduction must represent its own actions and decisions to itself, and sometimes communicate them to other animals as well. As the brain tries to create a model of its own decisions, it gets trapped in an infinite digression, and abracadabra! Out of this loop, consciousness pops out.

Fifty years ago this might have sounded plausible, but not in 2016. Several corporations, such as Google and Tesla, are engineering autonomous cars that already cruise our roads. The algorithms controlling the autonomous car make millions of calculations each second concerning other cars, pedestrians, traffic lights and potholes. The autonomous car successfully stops at red lights, bypasses obstacles and keeps a safe distance from other vehicles – without feeling any fear. The car also needs to take itself into account and to communicate its plans and desires to the surrounding vehicles, because if it decides to swerve to the right, doing so will impact on their behaviour. The car does all that without any problem – but without any consciousness either. The autonomous car isn’t special. Many other computer programs make allowances for their own actions, yet none of them has developed consciousness, and none feels or desires anything.

6

If we cannot explain the mind, and if we don’t know what function it fulfils, why not just discard it? The history of science is replete with abandoned concepts and theories. For instance, early modern scientists who tried to account for the movement of light postulated the existence of a substance called ether, which supposedly fills the entire universe. Light was thought to be waves of ether. However, scientists failed to find any empirical evidence for the existence of ether, whereas they did come up with alternative and better theories of light. Consequently, they threw ether into the dustbin of science.

The Google autonomous car on the road.

© Karl Mondon/ZUMA Press/Corbis.

Similarly, for thousands of years humans used God to explain numerous natural phenomena. What causes lightning to strike? God. What makes the rain fall? God. How did life on earth begin? God did it. Over the last few centuries scientists have not discovered any empirical evidence for God’s existence, while they did find much more detailed explanations for lightning strikes, rain and the origins of life. Consequently, with the exception of a few subfields of philosophy, no article in any peer-review scientific journal takes God’s existence seriously. Historians don’t argue that the Allies won the Second World War because God was on their side; economists don’t blame God for the 1929 economic crisis; and geologists don’t invoke His will to explain tectonic plate movements.

The same fate has befallen the soul. For thousands of years people believed that all our actions and decisions emanate from our souls. Yet in the absence of any supporting evidence, and given the existence of much more detailed alternative theories, the life sciences have ditched the soul. As private individuals, many biologists and doctors may go on believing in souls. Yet they never write about them in serious scientific journals.

Maybe the mind should join the soul, God and ether in the dustbin of science? After all, no one has ever seen experiences of pain or love through a microscope, and we have a very detailed biochemical explanation for pain and love that leaves no room for subjective experiences. However, there is a crucial difference between mind and soul (as well as between mind and God). Whereas the existence of eternal souls is pure conjecture, the experience of pain is a direct and very tangible reality. When I step on a nail, I can be 100 per cent certain that I feel pain (even if I so far lack a scientific explanation for it). In contrast, I cannot be certain

that if the wound becomes infected and I die of gangrene, my soul will continue to exist. It’s a very interesting and comforting story which I would be happy to believe, but I have no direct evidence for its veracity. Since all scientists constantly experience subjective feelings such as pain and doubt, they cannot deny their existence.

Another way to dismiss mind and consciousness is to deny their relevance rather than their existence. Some scientists – such as Daniel Dennett and Stanislas Dehaene – argue that all relevant questions can be answered by studying brain activities, without any recourse to subjective experiences. So scientists can safely delete ‘mind’, ‘consciousness’ and ‘subjective experiences’ from their vocabulary and articles. However, as we shall see in the following chapters, the whole edifice of modern politics and ethics is built upon subjective experiences, and few ethical dilemmas can be solved by referring strictly to brain activities. For example, what’s wrong with torture or rape? From a purely neurological perspective, when a human is tortured or raped certain biochemical reactions happen in the brain, and various electrical signals move from one bunch of neurons to another. What could possibly be wrong with that? Most modern people have ethical qualms about torture and rape because of the subjective experiences involved. If any scientist wants to argue that subjective experiences are irrelevant, their challenge is to explain why torture or rape are wrong without reference to any subjective experience.