Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow (24 page)

Read Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow Online

Authors: Yuval Noah Harari

Brands are not a modern invention. Just like Elvis Presley, pharaoh too was a brand rather than a living organism. For millions of followers his image counted for far more than his fleshy reality, and they kept worshipping him long after he was dead.

Left: © Richard Nowitz/Getty Images. Right: © Archive Photos/Stringer/Getty Images.

Prior to the invention of writing, stories were confined by the limited capacity of human brains. You couldn’t invent overly complex stories which people couldn’t remember. With writing you could suddenly create extremely long and intricate stories, which were stored on tablets and papyri rather than in human heads. No ancient Egyptian remembered all of pharaoh’s lands, taxes and tithes; Elvis Presley never even read all the contracts signed in his name; no living soul is familiar with all the laws and regulations of the European Union; and no banker or CIA agent tracks down every dollar in the world. Yet all of these minutiae are written somewhere, and the assemblage of relevant documents defines the identity and power of pharaoh, Elvis, the EU and the dollar.

Writing has thus enabled humans to organise entire societies in an algorithmic fashion. We encountered the term ‘algorithm’ when we tried to understand what emotions are and how brains function, and defined it as a methodical set of steps that can be used to make calculations, resolve problems and reach decisions. In illiterate societies people make all calculations and decisions in their heads. In literate societies people are organised into networks, so that each person is only a small step in a huge algorithm, and it is the algorithm as a whole that makes the important decisions. This is the essence of bureaucracy.

Think about a modern hospital, for example. When you arrive the receptionist hands you a standard form, and asks you a predetermined set of questions. Your answers are forwarded to a nurse, who compares them with the hospital’s regulations in order to decide what preliminary tests to give you. She then measures, say, your blood pressure and heart rate, and takes a blood test. The doctor on duty examines the results, and follows a strict protocol to decide in which ward to hospitalise you. In the ward you are subjected to much more thorough examinations, such as an X-ray or an fMRI scan, mandated by thick medical guidebooks. Specialists then analyse the results according to well-known

statistical databases, deciding what medicines to give you or what further tests to run.

This algorithmic structure ensures that it doesn’t really matter who is the receptionist, nurse or doctor on duty. Their personality type, their political opinions and their momentary moods are irrelevant. As long as they all follow the regulations and protocols, they have a good chance of curing you. According to the algorithmic ideal, your fate is in the hands of ‘the system’, and not in the hands of the flesh-and-blood mortals who happen to man this or that post.

What’s true of hospitals is also true of armies, prisons, schools, corporations – and ancient kingdoms. Of course ancient Egypt was far less technologically sophisticated than a modern hospital, but the algorithmic principle was the same. In ancient Egypt too, most decisions were made not by a single wise person, but by a network of officials linked together through papyri and stone inscriptions. Acting in the name of the living-god pharaoh, the network restructured human society and reshaped the natural world. For example, pharaohs Senusret III and his son Amenemhat III, who ruled Egypt from 1878

BC

to 1814

BC

, dug a huge canal linking the Nile to the swamps of the Fayum Valley. An intricate system of dams, reservoirs and subsidiary canals diverted some of the Nile waters to Fayum, creating an immense artificial lake holding 50 billion cubic metres of water.

1

By comparison, Lake Mead, the largest man-made reservoir in the United States (formed by the Hoover Dam), holds at most 35 billion cubic metres of water.

The Fayum engineering project gave pharaoh the power to regulate the Nile, prevent destructive floods and provide precious water relief in times of drought. In addition, it turned the Fayum Valley from a crocodile-infested swamp surrounded by barren desert into Egypt’s granary. A new city called Shedet was built on the shore of the new artificial lake. The Greeks called it Crocodilopolis – the city of crocodiles. It was dominated by the temple of the crocodile god Sobek, who was identified with pharaoh (contemporary statues sometimes show pharaoh sporting a crocodile head). The temple housed a sacred crocodile called Petsuchos, who

was considered the living incarnation of Sobek. Just like the living-god pharaoh, the living-god Petsuchos was lovingly groomed by the attending priests, who provided the lucky reptile with lavish food and even toys, and dressed him up in gold cloaks and gem-encrusted crowns. After all, Petsuchos was the priests’ brand, and their authority and livelihood depended on him. When Petsuchos died, a new crocodile was immediately elected to fill his sandals, while the dead reptile was carefully embalmed and mummified.

In the days of Senusret III and Amenemhat III the Egyptians had neither bulldozers nor dynamite. They didn’t even have iron tools, work horses or wheels (the wheel did not enter common usage in Egypt until about 1500

BC

). Bronze tools were considered cutting-edge technology, but they were so expensive and rare that most of the building work was done only with tools made of stone and wood, operated by human muscle power. Many people argue that the great building projects of ancient Egypt – all the dams and reservoirs and pyramids – must have been built by aliens from outer space. How else could a culture lacking even wheels and iron accomplish such wonders?

The truth is very different. Egyptians built Lake Fayum and the pyramids not thanks to extraterrestrial help, but thanks to superb organisational skills. Relying on thousands of literate bureaucrats, pharaoh recruited tens of thousands of labourers and enough food to maintain them for years on end. When tens of thousands of labourers cooperate for several decades, they can build an artificial lake or a pyramid even with stone tools.

Pharaoh himself hardly lifted a finger, of course. He didn’t collect taxes himself, he didn’t draw any architectural plans, and he certainly never picked up a shovel. But the Egyptians believed that only prayers to the living-god pharaoh and to his heavenly patron Sobek could save the Nile Valley from devastating floods and droughts. They were right. Pharaoh and Sobek were imaginary entities that did nothing to raise or lower the Nile water level, but when millions of people believed in pharaoh and Sobek and therefore cooperated to build dams and dig canals, floods and droughts became rare. Compared to the Sumerian gods, not to mention the

Stone Age spirits, the gods of ancient Egypt were truly powerful entities that founded cities, raised armies and controlled the lives of millions of humans, cows and crocodiles.

It may sound strange to credit imaginary entities with building or controlling things. But nowadays we habitually say that the United States built the first nuclear bomb, that China built the Three Gorges Dam or that Google is building an autonomous car. Why not say, then, that pharaoh built a reservoir and Sobek dug a canal?

Living on Paper

Writing thus facilitated the appearance of powerful fictional entities that organised millions of people and reshaped the reality of rivers, swamps and crocodiles. Simultaneously, writing also made it easier for humans to believe in the existence of such fictional entities, because it habituated people to experiencing reality through the mediation of abstract symbols.

Hunter-gatherers spent their days climbing trees, looking for mushrooms, and chasing boars and rabbits. Their daily reality consisted of trees, mushrooms, boars and rabbits. Peasants worked all day in the fields, ploughing, harvesting, grinding corn and taking care of farmyard animals. Their daily reality was the feeling of muddy earth under bare feet, the smell of oxen pulling the plough and the taste of warm bread fresh from the oven. In contrast, scribes in ancient Egypt devoted most of their time to reading, writing and calculating. Their daily reality consisted of ink marks on papyrus scrolls, which determined who owned which field, how much an ox cost and what yearly taxes peasants had to pay. A scribe could decide the fate of an entire village with a stroke of his stylus.

The vast majority of people remained illiterate until the modern age, but the all-important administrators increasingly saw reality through the medium of written texts. For this literate elite – whether in ancient Egypt or in twentieth-century Europe – anything written on a piece of paper was at least as real as trees, oxen and human beings.

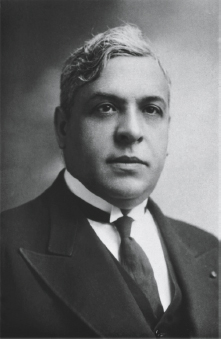

When the Nazis overran France in the spring of 1940, much of its Jewish population tried to escape the country. In order to cross the border south, they needed visas to Spain and Portugal, and tens of thousands of Jews, along with many other refugees, besieged the Portuguese consulate in Bordeaux in a desperate attempt to get the life-saving piece of paper. The Portuguese government forbade its consuls in France to issue visas without prior approval from the Foreign Ministry, but the consul in Bordeaux, Aristides de Sousa Mendes, decided to disregard the order, throwing to the wind a thirty-year diplomatic career. As Nazi tanks were closing in on Bordeaux, Sousa Mendes and his team worked around the clock for ten days and nights, barely stopping to sleep, just issuing visas and stamping pieces of paper. Sousa Mendes issued thousands of visas before collapsing from exhaustion.

The Portuguese government – which had little desire to accept any of these refugees – sent agents to escort the disobedient consul back home, and fired him from the foreign office. Yet officials who cared little for the plight of human beings nevertheless had deep respect for documents, and the visas Sousa Mendes issued against orders were respected by French, Spanish and Portuguese bureaucrats alike, spiriting up to 30,000 people out of the Nazi death trap. Sousa Mendes, armed with little more than a rubber stamp, was responsible for the largest rescue operation by a single individual during the Holocaust.

2

Aristides de Sousa Mendes, the angel with the rubber stamp.

Courtesy of the Sousa Mendes Foundation.

The sanctity of written records often had far less positive effects. From 1958 to 1961 communist China undertook the Great Leap Forward, when Mao Zedong wished to rapidly turn China into a superpower. Mao ordered the doubling and tripling of agricultural production, using the surplus produce to finance ambitious industrial and military projects. Mao’s impossible demands made their way down the bureaucratic ladder, from the government offices in Beijing, through provincial administrators, all the way to the village headmen. The local officials, afraid of voicing any criticism and wishing to curry favour with their superiors, concocted imaginary reports of dramatic increases in agricultural output. As the fabricated numbers made their way up the bureaucratic hierarchy, each official only exaggerated them further, adding a zero here or there with a stroke of a pen.

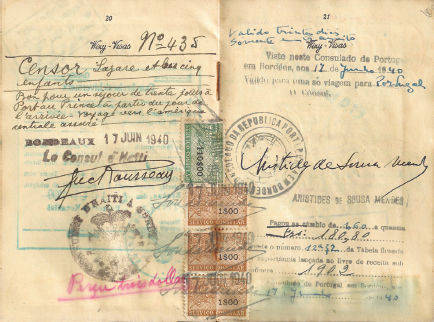

One of the thousands of life-saving visas signed by Sousa Mendes in June 1940 (visa #1902 for Lazare Censor and family, dated 17 June 1940).

Courtesy of the Sousa Mendes Foundation.

Consequently, in 1958 the Chinese government was told that annual grain production was 50 per cent more than it actually was. Believing the reports, the government sold millions of tons of rice to foreign countries in exchange for weapons and heavy machinery, assuming that enough was left to feed the Chinese population. The result was the worst famine in history and the death of tens of millions of Chinese.

3

Meanwhile, enthusiastic reports of China’s farming miracle reached audiences throughout the world. Julius Nyerere, the idealistic president of Tanzania, was deeply impressed by the Chinese success. In order to modernise Tanzanian agriculture, Nyerere resolved to establish collective farms on the Chinese model. When peasants objected to the command, Nyerere sent the army and police to destroy traditional villages and forcefully move hundreds of thousands of peasants onto the new collective farms.