Horsekeeping (47 page)

Authors: Roxanne Bok

“Well, no one does this unless they love it,” Bobbi said, staring intently into her coffee mug.

“I couldn't imagine doing anything else.” Meghan's eyes envisioned offices and subways.

“There's no way I could sit in an office all day or live in a city,” Brandy stated with conviction.

I snooped about their boyfriends, teased them about the eligible young bankers at Scott's firm and suggested that they plan a casual jumping demonstration during the lunch under the gazebo. They were

hesitant, out of shyness and humility, but I was eager to pit their skills against these machismo banker types. I also had this vague romantic notion of playing match-maker. They sensed my not so deft subterfuge.

hesitant, out of shyness and humility, but I was eager to pit their skills against these machismo banker types. I also had this vague romantic notion of playing match-maker. They sensed my not so deft subterfuge.

“I'm never getting married,” Brandy protested.

“Me neither,” Meghan agreed.

“Good idea,” Bobbi and I advised, two wise old mares hitched for life.

Â

Â

THE NEXT WEEKEND, rain soaked our hikers but slowed in time for lunch. The bankers survived Scott's fast-paced climb despite a late night of heavy drinking and gathered in the gazebo to enjoy the farm scenery. In the ring, Meghan and Brandy exercised and jumped Toby and Bandi to enthusiastic applause. Little did we know, one member of the group, Santiago, had been on the equestrian team at Yale and spent the better part of his Mexican youth around horses. Several years had slipped by since he last rode, and Bobbi immediately sensed his itch to get back in the saddle. We set him up. A little rusty, he nevertheless took a few jumps on Bandi much to the amusement of his colleagues who phone-photographed his prowess with plans to email them around the office. His colleagues truly impressed, Santiago's ride served as a point of connection between the urban and the rural bipeds.

At dinner, the day's events provoked much horse talk. Still charged from his unexpected ride, Santiago discussed everything equine with Meghan and Brandy through the cocktail hour and beyond. Scott and I left to put our tired old bodies in bed as the bankers invited the girls to visit their vertically stacked stables in the concrete and steel paddocks of NYC. Having to rise for the 7 a.m. barn work, Meghan and Brandy responsibly departed while the urban refugees drank The White Hart dry. Scott and I enjoyed merging these two worlds, horsekeeping and financial dealing. We hung out with talented, delightful young people, and it prompted us to imagine what our own children might achieve, be it in a high rise or a barn.

Â

Â

AT THE END OF JULY, Bobbi and I stood by the paddocks, in despair at our still raw fences. The painter never had shown up.

“We should give up on Mike and get someone else,” I said.

“I asked around but everyone's booked this late in the season.” Bobbi pulled a thorny thistle from the base of a post.

Just then a cowboy-booted, jean-clad, thumbs-pocketed stranger sauntered down the path into Weatogue Stables.

“Howdy, ladies. Beautiful day,” he greeted, tipping his hat. “Know anyone with fences that need paintin'?”

Our eyebrows shot north, and we summoned that creepy Twilight Zone music:

doo doo doo doo, doo doo doo doo

. . . .

doo doo doo doo, doo doo doo doo

. . . .

“Um, yeah,” we both stammered. “We do.”

Our Kentuckian smoothly “yes maam”ed us into paying his first price, not that we had any negotiating room. Facing another winter of exposed wood, we hired this unknown feller's theoretical crew as the manna from heaven they might be, arranged a fast, weekend cash deposit half expecting a jilt, and crossed our fingers. Our southern gentleman was the real deal: his team delivered the oily black paint and sprayed like crazy, and it was good, except that the horses ignored the “Wet Paint” signs.

For several weeks we dealt with sticky, painted bodies, and good-natured boarders who agreed that happy, outdoor-paddocked zebras were better than cranky indoor-stalled horses. Pints of baby oil helped dissolve the abstract artwork from the horses' faces, butts, necks and legs. No wonder these fences already showed wear, breaking and bending with unfathomable regularity; we now had visible evidence of every horse's scratch, rub and push against them. Late in September itchy-butted Cleo was still managing to find damp recesses of posts and rails, but how wonderful to complete the last major job and finally declare the farm officially finished. And what a satisfying, if latent, transformation: the wood of thirteen large paddocks going almost black from sandy brown outlined, as ink enhances a pencil sketch, our farm's etching. “It's beautiful,” our watchful neighbors expressed, and we swelled with pride.

The construction phase of Weatogue Stables drew to a close and so did my glorious summer.

The construction phase of Weatogue Stables drew to a close and so did my glorious summer.

On Labor Day, just hours before my family's annual migration to NYC, Bobbi arranged a swan song summer ride. In preparation for the remaining events of the season, she, Brandy, Cindi and I took three horses to Riga Meadow's show-ready jump field.

Oh-oh

, I thought,

another jump field

. But my summer's work emboldened me. Brandy's new

beau

Jason tagged along to explore exactly what his girlfriend did for a living. I found myself expounding about everything equine.

Oh-oh

, I thought,

another jump field

. But my summer's work emboldened me. Brandy's new

beau

Jason tagged along to explore exactly what his girlfriend did for a living. I found myself expounding about everything equine.

“I heard you should never walk around the back of a horse,” Jason said as I saddled Bandi, tied loosely to the horse trailer.

“Well most people do the exact wrong thing when they do,” I explained with some authority, trying to bolster my own confidence and take my mind off the jumps spread across the slippery, uneven grass.

“It's important to let the horse know you're there by laying a hand on his butt as you go around. Don't try to sneak in the hopes of not surprising him.” I demonstrated, and Bandi, surprised, scooted forward two paces.

“And the distance is important. It's tempting to allow just enough space to get walloped good and hard. You should either stick really close to limit the momentum of any kick or allow a wide distance that puts you out of reach.”

It felt good to recite technique that I understood from actual experience, one that bucks intuition and that I coached myself on many a time. I still fought my inclination to arc that dangerous one or two feet away from the back end, and because my knowledge was so hard-earned, I felt compelled to wax eloquent to Jason, who was as green as me a year before.

“There's telepathy, a communication of touch that develops between you and the horse after a while. You learn how to move around each otherâa two-way comfort level that makes it safer.”

As I spoke those very words I lost focus on my task at hand, forgetting that I was not in the confines of grooming stall walls with cross ties.

Bandi shuffled sideways away from the trailer and high-stepped his back right hoof down hard on my left three littlest toes.

Bandi shuffled sideways away from the trailer and high-stepped his back right hoof down hard on my left three littlest toes.

“OUCH,” I cried as I jumped back, pushing Bandi's butt over and pulling forcefully to extricate my foot. Pain sweat instantaneously broke from my pores. I wrenched my toes back but my boot tip remained wedged. Luckily he didn't fully settle, unpinning me as I shoved him away, but not before crunching my toes enough that I assumed they were broken. Nausea gathered in my stomach.

“Here I am explaining how not to get kicked and then I get stepped on.” Red-faced, I tested my toes slowly.

“Well, he moved pretty quickly,” Jason graciously conceded.

“Yeah, he's quick alright,” I muttered, my smug expertise gone. “He's a Quarter Horse, bred to be the fastest horse over the quarter mile.”

My toes were bruised, and my pride too, but the humble rest of me rallied. I proceeded to jump five small fences in a row, badly, but I did itâthree times. Brandy took the course spectacularly on Toby, and Jason and I cheered (quietly, so as not to spook her horse) her command of the oafish, overly “happy” (Bobbi's euphemism for “dangerously excited”) Tobster. But everyone recognized it more as a milestone for scaredy-cat, over-the-hill me, who had previously dredged up any excuse against Bobbi's suggestions of equine road trips in general, and we slid it in just under the wire, the last official day of my summer vacation. Exiting the season on such a high note made it that much harder to ride only once a week and learn at the much slower pace of my kids' school year. There was no substitute for daily hours in the saddle. And in those long winter months I really missed my horse; I mooned over his photo front and center on my bulletin board and day-dreamt of him running, in the early morning light, across the frosty paddocks.

CHAPTER TWENTY-THREE

The Scene of the Crime

A

YEAR HAD PASSED since I first showed Bandi at Riga Meadow, where my beginner's luck had won me my only blue ribbon one day after my toss off Bandi, both events hair-raising personal firsts. Bobbi and I decided our barn should enter Riga's September show again.

YEAR HAD PASSED since I first showed Bandi at Riga Meadow, where my beginner's luck had won me my only blue ribbon one day after my toss off Bandi, both events hair-raising personal firsts. Bobbi and I decided our barn should enter Riga's September show again.

Bobbi bucked my automatic reluctance to join in the “fun” once again. “This will be old hat now. You've come so far.”

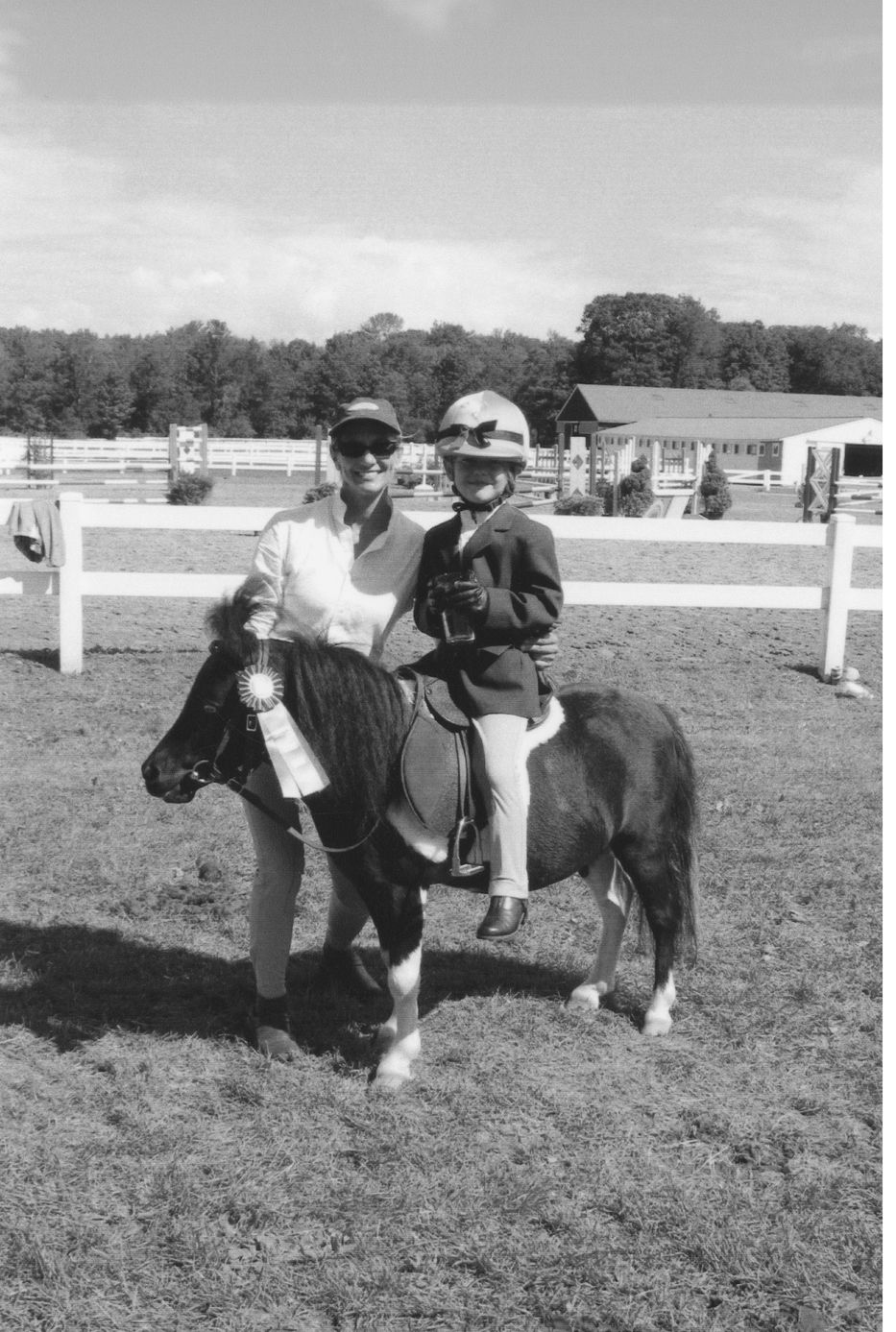

She was right. With a full summer of riding under my belt, I was an adequate, if not fully secure, equestrienne. My ride over the jumps on Labor Day boosted my confidence, and though the memory of that first show still weakened my knees, this year I slept soundly the night before and awoke eager rather than a quaking wimp. This time, three members of my family were participating. Jane was hoping to improve her lead line walk/trot fifth of five finish, and Elliot would debut. His four classes and my three brought cantering and jumping cross rails into the mix, so together we faced new territory.

Weatogue Stables was well-represented: early Saturday morning Bobbi trailered our seven horses, in twos, the eight miles to Riga Meadow. To avoid a fourth trip, she wedged the mini Hawk sideways in the tack compartment of her trailer, strictly admonishing Bandi and Willy to behave. Packing for and moving seven horses and nine riders was complicated: in admiration I watched the girls remember everything from Showsheenâa mane and tail beautifierâto treats, crops to bridles, saddles

to hoof oil. They had been up since 5 a.m. and at the barn until midnight Friday bathing horses, braiding manes, polishing and organizing tack, but they couldn't fix the weather. Three to four inches of rain fell on Friday. Saturday morning I cut through the early morning fog and arrived at Riga Meadow to find a soppy outdoor ring with two small lakes wind-rippling at the far end.

to hoof oil. They had been up since 5 a.m. and at the barn until midnight Friday bathing horses, braiding manes, polishing and organizing tack, but they couldn't fix the weather. Three to four inches of rain fell on Friday. Saturday morning I cut through the early morning fog and arrived at Riga Meadow to find a soppy outdoor ring with two small lakes wind-rippling at the far end.

“No one can ride in this,” I told Bobbi, assuming a collective retreat.

“Oh, this is nothing. You should see some of the hunter pace showsâit's hard to tell the horses from the riders everyone's covered in so much mud. Horse shows take place no matter what.”

We found Bobbi's friend Cindi and her niece Kaylee both set to ride, and Terri, who kindly came as groom to choreograph this dance of Weatogue pairs crisscrossing overlapping events. Unlike in dressage competitions, there are no predetermined riding times at hunter jumper shows, only a sequence of classes simultaneously run on two fields that unfold as they may. We had to watch and be ready. Though Bobbi was not riding until late, she had eight riders to baby-sit; being the oldest, I couldn't monopolize her. Elliot and I nodded at our instructions where to be and when and settled into preparation. I paid our fees and from the organizer's tent collected our black numbers on white cardboard that we strung around our waists. I drew forty-seven, my age, which I hoped signaled luck. Elliot helped me tack up Bandi, and we headed outside.

“Good luck, Mom.”

“You too, El.” I took a deep breath and saddled up.

The grounds were not as busy as last September, the weather good for something at least. My warm-up went well both in the ring and on the slick grass. Elliot played photographer and Bandi and I hammed it up; we laughed and relaxed. During the ring practice Bandi sloshed unperturbed through the water both at a trot and a canter, at ease and willing to go. He enjoyed showing and picked up his game in response to my aids.

Other books

Everything is Everything Book 2 by Pace, Pepper

Beverly Hills Maasai by Eric Walters

Night Call (Night Fever Serial Book 2) by Hawkins, Jessica

Taking Connor by B.N. Toler

Shadow Girl by Patricia Morrison

The Crush by Scott Monk

Wicked Werewolf Secret (The Werewolf Society) by Jones, Lisa Renee

Plender by Ted Lewis

Mystery of Tally-Ho Cottage by Enid Blyton