How to Be Alone (School of Life) (9 page)

Read How to Be Alone (School of Life) Online

Authors: Sara Maitland

Tags: #Politics & Social Sciences, #Philosophy, #Self-Help, #Personal Transformation, #Self-Esteem

This particular story, and its explicit articulation that it is ‘not good’ for people to be alone, has been extremely influential, but it is not by any means unique; many other creation myths see the forming of human social units (often based on the sexually related couple, though sometimes on a sibling group) as a key moment in human development.

These myths are endorsed by popular science. The idea that human beings are a social species is not simply firmly embedded in our culture; it is supported by evolutionary theory, social anthropology and archaeology. And obviously it does have some validity; because of reproduction, virtually no animals can be entirely solitary, but there is enormous variety in their sociability. Some species of hamsters, for example, live extremely solitary lives, meeting each other very occasionally and almost exclusively for sex; other species, like ants or termites, are so highly socialized that huge numbers of the members of any particular colony are not even capable of reproduction but devote themselves to the very highly organized support of their fertile ‘queen’ and her young. But on the whole, popular ‘sociobiologists’ do not write bestsellers about termites and hamsters. They prefer more glamorous species.

Most of our closer animal relatives, particularly primates – and specifically chimpanzees, with whom we share a full 98 per cent of our genetic makeup – are social beyond the direct biological needs of feeding, reproduction and child-rearing: they play, groom each other, compete and fight, cooperate, exchange a range of vocalizations and continue to have relationships with their own weaned – even mature – offspring. For most primates their social relations transcend immediate family groups. Like humans, it is apparently unnatural for primates to be alone.

Homo sapiens

have one particular behaviour that is not shared with other primates – organized hunting. The collective hunt is, inevitably, a communal and social experience. It has even been suggested that it is hunting as a group that led to the development of language, and the anthropological and archaeological evidence strongly supports the idea that the original human societies were hunter-gatherers.

Because of this there has been a tendency to compare ourselves and our social needs to other species who also hunt collectively – especially wolves and lions.

But in making the claim that being alone is unnatural because we are fundamentally like other primates and hunting species, it is important to take a wider view of a species’ ‘lifestyle’.

Lion packs are female-led. However, a newly arrived male lion will kill all the immature offspring of his predecessor. We would not justify such behaviour in human societies on the grounds that it was ‘natural’.

Wolves are highly gregarious. But their social groups are organized on entirely familial lines. A pack usually consists of a group of sisters and their young and a single non-related male: if I set up house with my sisters, sharing a single man as a sexual partner and the father of all our children, this would not be seen as a ‘natural’ relationship.

Nonetheless, the popular argument that it is somehow unnatural for human beings to be alone claims a scientific basis in the behaviours of primates and hunting-pack species. And to some extent this makes good sense: humans have a biological need for sociability, if for no other reason than that it takes so long for our young to become independent; our survival requires us to support and protect these generally pretty useless and vulnerable members, and that in itself needs some sort of social interaction (unlike, say, salmon, whose mothers abandon their eggs before they are even fertilized, let alone hatched). All the archaeological evidence of the earliest human societies, together with the anthropological studies of different societies, make clear that

Homo sapiens

is a social species and cements survival through a complex web of practical, kinship and cultural structures. It is ‘natural’ for humans to associate, cooperate and bond both emotionally and ritually.

But it is wrong to assume that this necessary sociability, even in the obviously complex forms that exist among primates, means that individuals of other species never spend time alone. This is simply not the case.

Gorillas, for example, despite living in groups, spread out and forage alone. They are capable of a range of vocalizations with distinct meanings – about twenty-five different sounds (‘words’) have been identified by researchers. One of the most common of these is a loud ‘hoot’, which can be heard for at least half a mile (0.8 km): obviously you do not need to communicate audibly over such a distance if you are never separate from the rest of your social group.

Gorillas also sleep alone. Each evening they ‘make camp’, constructing new individual nests either on the ground or in trees. A suckling baby gorilla nests with its mother, but as soon as it is weaned at about three years old, she teaches it to make its own nest and it sleeps there. Many animals sleep together even as adults, but the highly socialized gorillas (and other primates too) sleep by themselves.

Meanwhile orangutans, which are as nearly related to humans as gorillas, are far more solitary in their lifestyle. This species spends most of its daily life alone, although its young are more gregarious.

And not all lions or wolves live in packs: both species have a second form of organizational behaviour – individuals who live alone: the lone wolf and the nomad lion. Both lions and wolves may maintain this status for life, or move in and out of it, setting up new prides or packs. These less-socialized individuals are not rare and are not created by external or unusual traumas – they are, apparently, perfectly ‘natural’.

Culturally we like the idea of the close-knit social group, so we tend to ignore how much hunter-gatherer activity is best done alone. The socially organized big-game hunt is surprisingly inefficient: kill rates vary from as low as 17 per cent up to about 40 per cent, which is not going to keep a community in food. Fishing, small-animal hunting and a great deal of vegetable gathering are frequently done alone. The more northerly, tundra-and taiga-based hunter-gatherer societies are more dependent on meat, since there is less edible vegetation: their huge and famously complex reindeer hunts are highly socialized and collaborative – different small groups coming together to build elaborate traps and fences and runs to exploit the reindeer-herd migrations. But these spectacular events are seasonal (like the Common Shearing I discussed earlier) and can as easily be seen as ‘leisure’; most gathering and hunting and fishing is done more quietly alone.

The more, and the more sensitively, we look at what actually happens out there, beyond the boundaries of modernity – at the complexity of models and forms of social being – the more we will be sceptical about

anything

being purely ‘natural’ or ‘unnatural’. We will most certainly become increasingly aware that solitude, in greater or smaller quantities, is simply a normal part of how it is to be.

Gorillas sleep alone.

5. Learn Something by Heart

This suggestion may come as something of a surprise. What does the tedious, old-fashioned task of rote learning have to do with strengthening your capacity for and enjoyment of being alone? Didn’t we break away from that dead educational model decades ago? Now we have the Internet, and calculators and mobile phones, why on earth would we want to clog up our brains with those repetitive factoids – like times tables, irregular verbs and the dates of the kings of England?

There are a whole series of counterarguments and answers to these sorts of questions, beginning with the observation that there are other richer things to learn by heart – and note all the connotations of ‘heart’ here; they include love

and

rhythm. If you find times tables or historical dates boring, learn something else – poetry, a foreign language, the periodic table. But there are two particular answers which relate very closely to the joys of solitude and the fear of being alone: a well-stocked mind enhances creativity, and a mental store of beautiful or useful items offers security, frees one from complete dependence on oneself and appears to aid balance and sanity in solitude.

I have already suggested that solitude may be a necessity, and it is certainly a well-established aid to creativity. One reason why this is so is that the social presence of others distracts or reconstructs a person’s sense of their core self. So if, seized with inspiration, you need some material for your creative impulse to work on, you will undermine your own project if you have to turn outside yourself to grasp the necessary information. Wordsworth’s famous poem ‘Daffodils’ would have a very different effect if it ended:

For oft, when on my couch I lie

In vacant or in pensive mood,

I have to rise and go and search

On Flickr, Google or YouTube.

The capacity to be creative is profoundly linked to the ability to remember: the word ‘remember’ derives from ‘re-member’, to ‘put the parts back together’. So strongly was this felt to be the case that classical Greek mythology made Memory ‘the mother of the Muses’.

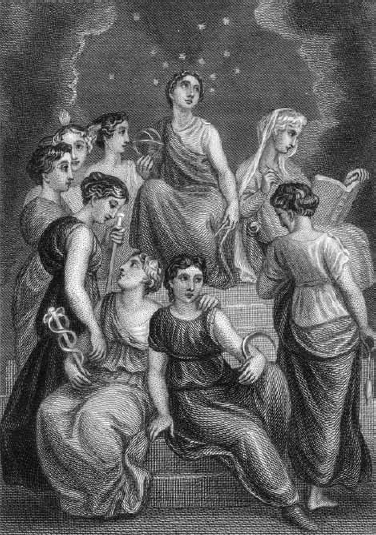

The Muses: Nine beautiful nymphs who represented the arts and inspired artists. Their mother was Mnemosyne—memory.

The Muses were the nine beautiful nymphs, the young women who represented the arts and inspired artists: Calliope (epic poetry); Clio (history); Euterpe (flutes and lyric poetry); Thalia (comedy and pastoral poetry); Melpomene (tragedy); Terpsichore (dance); Erato (love poetry); Polyhymnia (sacred poetry); Urania (astronomy). Their father was Zeus, the chief of all the Gods, and their mother was Mnemosyne – memory. We still use the word ‘muse’ to describe a woman who is an abiding influence on a male artist.

Children’s memories used to be trained from primary school, but so-called ‘rote learning’ has gone out of fashion. A number of people, including me, think this is a pity. There is a good deal to be said in favour of ‘learning by heart’.

The argument in favour of memorizing ‘scales or times tables or verse’ … has been attacked for years now – unfairly … Sense and memory are allies … Rote learning is more like training than learning. It is the trellis on which a free thinker can climb … ‘Memorization’ used to be almost a synonym for ‘culture’. [Now] it is a party trick … a waste of time … [Education] ‘can only come from the initial submission of the student’s mind to the body of knowledge contained within specific subjects’.… In education, submission is empowerment.

(Christopher Caldwell,

Financial Times,

16 November 2012)

What we have memorized, learned by heart, we have internalized in a very special way. The knowledge is now part of our core self, our identity, and we can access it when we are alone: we are no longer an isolated fragment drifting in a huge void, but linked through these shared shards of culture to a larger, richer world, but without losing our ‘aloneness’. For many people this resource, this well-stocked mental larder, offers food for thought, for coherence, for security, and must be one of the factors that turns ‘isolation’ into creative solitude. This is a kind of cultural engagement that you cannot get from the web or from reading.

Another benefit of having a rich and multilayered collection of memorized material ready to hand, as it were, is more anecdotal. Solitary confinement, especially if accompanied by fear, uncertainty or sensory deprivation, really does induce psychosis and lead to the breakdown of even apparently tough individuals. It is therefore worth looking carefully at the individuals who survive such experiences intact; they obviously have an exceptional skill at being alone and we can learn from them. Over and over again this small and admirable group reports the value of having deep-laid, secure material in one’s memory bank.

In 1949 Edith Hajos Bone was arrested in Hungary, where she was working as a journalist. She was kept in solitary confinement – often in the dark, sometimes in the wet, without any recreational facilities (like books or even sewing), subjected to occasional interrogation sessions, and never told what she was charged with or given any information about her future at all: all precisely the features most likely to lead to serious mental breakdown. She survived apparently entirely untouched. She ascribed this to her own mental discipline and intellectual resources. On a daily basis she would walk herself, imaginatively, round cities she had visited; recite poetry – and translate it from one language to another; keep in touch with her own body through the careful medical details she had had to learn by heart as a student doctor. In her autobiography she mentions several other sources of ‘amusement’, which relied on a well-filled mind: for example, she extracted threads from her towel and wove them into cords: