How to Be Black (3 page)

Authors: Baratunde Thurston

When Did You First Realize You Were Black?

F

or Americans, some days are unforgettable: the day JFK was assassinated, the day Osama bin Laden was killed, the day Flavor Flav's Fried Chicken restaurant went out of business. For many black Americans, a similarly unforgettable experience takes place the day you realize you're black, and if it's not a moment of black self-awareness, it's probablyâneverthelessâthe moment you were introduced to the idea of black as something negative.

I recall three moments of black self-awareness.

The first moment occurred in kindergarten.

My mother worked in Washington, DC's, L'Enfant Plaza at the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency.

*

Across the street, the Department of Housing and Urban Development ran a kindergarten in its child-care center. The HUD building has a distinctive design: a curved concrete structure in the shape of an elongated X with evenly spaced, recessed windows arrayed in a precise grid. When seen in conjunction with the storm trooper outpostâlooking parking attendant booth, it felt as if we were on the set of

Star Wars

. Tucked away at an interior corner of a courtyard was the child-care center's playground. That's where I developed a crush on a little girl in my class (insofar as a four- or five-year-old even knows what that means).

I would demonstrate this by throwing things at her and singing Paul McCartney and Stevie Wonder's “Ebony and Ivory” in her general direction. She was white.

I don't remember anyone making a big deal of our racial differences, but I remember noticing them myself. Also, I sang “Ebony and Ivory” at her, which I still can't believe. The next year, she and I had moved on to different worlds, and I became obsessed with the song “Uptown Girl” by Billy Joel. Not until writing this book did I realize how perfect for the situation the lyrics of that song are. Essentially, she was living in her “whitebread world” and I was her “downtown man.” Could you imagine a more perfect metaphor? I don't think so.

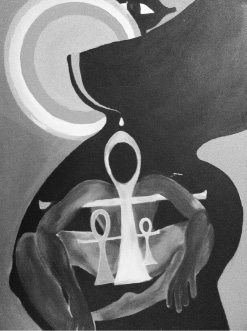

The second moment of black self-awareness came courtesy of my mother and her sense of interior design. Our household was stocked with images of proud blackness: a Malcolm X portrait, stacks of jazz, soul, funk, and R&B records, and two massive paintings, one integrating a set of ankhs

*

and the other of a Black Power fist. It's hard not to know you're black when you're physically surrounded by it on a daily basis.

This painting loomed over me on the walls of my early childhood home.

The third moment of awareness occurred on a childhood camping trip with my mother and my friend Reginald somewhere in Virginia, I think. Reggie and I were playing alone in the nearby lake when a little white boy approached us from the shore and loudly announced, “There's niggers in the water! Look at the niggers!” I like to imagine that our first reaction was to spin around, searching and frantically yelling, “Where!? Niggers? Let me at 'em! Where are they?”

Reggie and I had a hard choice to make in that moment. The reason we knew each other is that we were in karate classes together back in DC, and we were very good at karate. We conferred on whether or not to use our combined karate skills to kick this little racist's ass, but considering our location in the Who-Knows-Where Woods of Probably, Virginia, we decided against it. In that moment, the black pride I absorbed in my home was balanced by the embarrassment, rage, paranoia, and self-restraint that often accompany blackness in the outside world of America.

Most black people have their own coming-of-blackness story, and in the process of putting this book together, I conducted interviews with several friends and professional colleagues I thought could lend an alternate, and often more eloquent, voice to the questions raised by

How to Be Black

. Here are the members of The Black Panel recalling their first realizations of being black or what blackness meant.

W. KAMAU BELL

I first realized I was black when I was in first grade at a small, private school in Boston. I was playing doctor with a bunch of kids and this one girl, it was her turn to kiss me, and she didn't, and she ran away laughing, and the other kids ran away laughing. And the thing I realized at that point [was] that I was black and they were all white.

That was the first time I remember feeling like black was somehow separate from the norm. I think I knew I was black before then, because my mom would not have let me

not

know I was black. There would have been no way that she would have let that information slip. “It's cold outside. Take a jacket. And you're black.”

CHERYL CONTEE

I first realized I was black in nursery school, when a little girl told me that I was black. And I told her, “No, I'm beige.” I knew what beige was, even though I was four, because I went shopping a lot with my mother and grandmother, and so I knew taupe, beige, and the difference between the two. And I could read, and I knew from crayons, I knew the color beige. I used it a lot to draw myself.

So I was really disturbed, because she held her ground. She was fairly certain that I was black. So I came home, and I remember I couldn't really move past the entrance of the house. And I needed to talk about the fact that this little girl said that I was black, and that I, in fact, found myself to be beige. [My parents] reacted like any black intelligentsia: we went to the library.

I would actually call it a series of seminars for my brother and me, in terms of African-American culture through the ages, going back to Egypt, actually. And I remember the Saturday when we went to the big library in Wheaton. We didn't go there except for special occasions.

ELON JAMES WHITE

I first knew I was black when I was a child and my mother and my uncle yelled at me because I had a broken thought process on race. They were talking about how the cops were dealing with black people, and I started to explain to them that “Maybe if black people stopped committing so many crimes, then the cops would leave them alone,” and they stared at me. Then I was like, “Well, I'm a black male, and I haven't been arrested for anything, so obviously it's not just being black.”

And then they cried.

DAMALI AYO

My first memory of realizing I was black was told to me by my mom. There's two. I remember being in tap dance class when I was two years old, and apparently I had a concern that the teacher would turn me white. So I was very aware early on that I liked being black and I wanted to stay that way.

And then my mother tells a story about going out to dinner at some point, and our family's out and I'm just a baby. And the waitress, white waitress, comes over and says, “What a cute little baby!” And I just go, “Ahhhh!” So my mother interprets that as a racial tension. I mean, maybe it was her perfume or something. But you know, my mom's read was, “My little daughter knew what was up.”

DERRICK ASHONG

I didn't know at first. I was born in Africa, so everybody was black. We don't really think about it like that. Here, everyone's like, “Is he black? Is he white? Is he black?” In Africa, you don't ask. The assumption is that you're black. Therefore, what becomes more important is other things. What your name is, where you come from, what language you speak, what's your culture, what's your tribe, et cetera. So I didn't know I was black.

When I was eight, I moved to the Middle East. I think the Middle East is the first time I discovered I was black, because people would come up to you, and they'd [say something in Arabic,] which translated to, “Hey, this is a black guy.”

Then I went to a British school in Doha. British people let you know you're black. They still were trying to hearken back to them old days. I'm like, “Dude, we is all free now, we are all free. You have nothing but this little island and the Falklands. You have nothing else.” But they will remind you.

I started to understand what it meant to be black insofar as an American context when I moved back to the States. I did [my last two years] of high school in suburban New Jersey.

I'm a city kid. I didn't know what the suburbs was like. I discovered it was not that nice. That's when I discovered that apparently being black is not good. Things like, “Black people are not supposed to be smart.” I had no idea. I'm messing around, getting As. Stupid ass. I thought you were supposed to be good. Little did I know that I should play more basketball, read less books. But this I learned when I got back here.

JACQUETTA SZATHMARI

I think I've always known I was black. I mean I grew up in a black neighborhood; it was never like a process of discovering I was black, but I can say I remember [the first time I was] insulted about being black. That's when I realized that maybe black could suck a little bit.

I was doing swimming lessons at 4H camp or a day camp kind of thing, I was going to go dive in the water, and some white kid made a comment about grease in my hair and how it was going to ruin the entire Chesapeake Bay. I was like, “Wow, okay, that's racism, and that's what it's going to mean for a little while for me to be black.”

CHRISTIAN LANDER

My whole life in Toronto, I was very, very aware of being white at a really young age. The [black] experience in Toronto is very different, because of the way immigration patterns worked. So most of our [black] population is actually Afro-Caribbean, people who moved up from Jamaica, Trinidad, Guyana. My understanding for most of my life about black culture was really more Caribbean-based.

I'd say I learned fairly early on from the Toronto experience, and the rest is really the American black experience, which came from media, television, and so forth.

You like how I included a white Canadian? Booyah. Diversity in

How to Be Black

? Check.

M

y family has been black for a long, long time.

While I have yet to pursue Harvard professor Henry Louis Gates's crime sceneâinvestigating, genealogical origin-hunter project,

*

I can go back a few generations based on stories my mother shared and documents my sister and I discovered after she passed in 2005.

My great-grandfather was named Benjamin Lonesome, and he was born in 1870 in Caroline County, Virginia. According to my mother, he was part Native American,

*

born a slave,

*

and taught himself to read. According to his obituary, he moved to Washington, DC, in 1896 and started working for the Highway Division of the DC government in 1900. He died at the age of ninety-six.

Based on the photos I've seen, he was tall, thin, and handsome. My mother held her grandfather in extremely high regard, so much so that I was named in his honor.

*

Benjamin Lonesome fathered two daughters, one of whom was my maternal grandmother, Lorraine Martin.

I don't have many memories of my grandmother. By the time I came along, she and my mother had an extremely frayed relationship, so I only saw her a few times. What I do remember is that she liked vodka and smelled of cigarettes, and her house had the aroma of their mutual accumulation. What I didn't know until after my mother's passing was that in 1954, my grandmother was hired as “the first colored clerk in the U.S. Supreme Court building,” according to the

Washington Afro-American

newspaper. When asked by the paper what she thought of working in the Supreme Court building, my grandmother described it as “sort of awe-inspiring.” The woman for whom she worked was a personnel officer named Catherine Waddle. When asked what she thought of my grandmother, Waddle described her as “just fine.”

My grandmother was highly respected in her community, directed the Sunday school choir at her church, and loved to travel. She didn't always love being a parent, though, and took the extraordinary step of sending my eight-year-old mother to an all-black boarding and reform school in Cornwells Heights, Pennsylvania. The Holy Providence School was founded by Katharine Drexel of the Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament, a Catholic religious order created to recruit Native Americans and blacks. Attending the school, though a year behind my mother, was Ed Bradley, who would become one of America's best-known journalists through his work on

60 Minutes

. Within ten years of my mother's time at Holy Providence, basketball legend Kareem Abdul-Jabbar would also attend. I remember my mother talking about her time at this school, but I don't know if she ever realized that some of her schoolmates went on to become some of the most prominent and successful black people in the country.

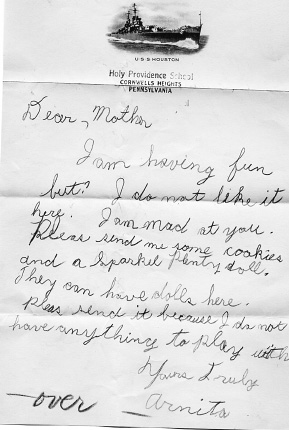

You don't need to have special qualifications in child psychology to imagine how being shipped off to a Catholic boarding school on the outskirts of Philadelphia would make a little DC girl feel. This letter written by my mother to her own mother captures the reality perfectly:

Dear, Mother

I am having fun but? I do not like it here. I am mad at you. Please send me some cookies and a Sparkle Plenty doll. They can have dolls here. Please send it because I do not have anything to play with.

Yours Truly,

Arnita

But the best part of the letter comes in the form of a note added by someone clearly not my mother. Written in a large, perfect script at the bottom of my mother's note is simply the word “Over,” and on the other side of the page in the same script is:

If your little girl is dissatisfied, we'd be glad to have her bed for children who are anxious to come.

Sister

A letter from the very young Arnita Thurston to her mother from boarding school.

Wow. That letter might as well have been signed “Warden.” These sisters weren't playing! They got all Patriot Act on a little girl's letter to her mother.

My mom didn't attend Holy Providence for long. After returning to DC, she went to Benjamin Banneker Junior High School and McKinley Technology High School, and for a while seemed to play and dress the part of the appropriate, God-fearing Negro woman my grandmother wanted her to be. I even have a photo of my mother sitting on the National Mall wearing a dress (below the knees) and holding a basket! How quaint. But my mother was also questioning her church's missionary activities to “save the heathens” in Africa, and she began socializing and politicking with blacks from across the Diaspora who lived in DC: Nigerians, Eritreans, Caribbean people, and black American activists.

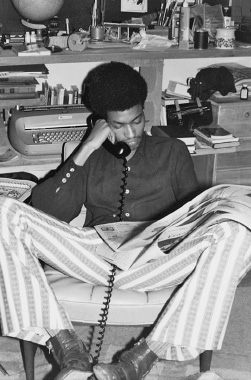

Soon she was partying with brothers named “El Dorado”âpicture a smooth, lanky brother with leather boots, blue-and-white-striped bell-bottoms, polyester dress shirt, and an afro that shone like the sunâand protesting in streets and on radio stations for black liberation. My mother was turning our family even blacker!

Arnita Thurston as Appropriate Negro Woman.

El Dorado aka The Coolest Dude Ever.

Arnita Thurston (center) as Revolutionary Black Woman.

My sister was born into the eye of the Radical Mama Thurston storm in 1968. She lived her first nine years with my mother in one of many centers of black cultural and political activity: the Envoy Towers apartment building on 16th Street in Northwest DC. My mother partied and played music in clubs and smoked reefer,

*

and her parenting style could be rough, relying heavily on the same corporal punishment she had received growing up.

I had a slightly different version of Arnita Lorraine Thurston. Shortly before my birth in 1977, my mother found a row house in a listing of estate sales, and she delivered phone books and sold home-cooked dinners to help raise the down payment for my childhood home at 1522 Newton Street. By the time I came along, eighty-one years after my great-grandfather had moved to DC, my mother no longer smoked, had mostly given up physically disciplining her children, and would increasingly become committed to an often-annoying health-food diet.

I recall her many experiments in healthy eating with some pain. We often shopped at a health-food cooperative, purchasing items like rice cakes; Grape-Nuts cereal, which was essentially gravel; and skim milk, which is like a watered-down version of the milk you know and love. I'll never forget waiting at the checkout counter of the Takoma Co-op and seeing “carob-covered” doughnuts, which should have been called “infuriatingly not-chocolate” doughnuts.

On nearly every trip to the co-op, we were the only black people in the market, and when my friends visited our home, they would notice that instead of Cheerios cereal, I had some absurd healthy alternative called Tasteeos. If the cereal were actually tasty, its name would not be Tasteeos. It was embarrassing!

My mother also had a deep affection for the outdoors, and she planned many family activities around long car rides, hiking, biking, and camping. Whoever said black folk don't go camping forgot to tell Arnita Thurston, who thoroughly enjoyed spending a Saturday afternoon tent-shopping at Recreational Equipment International (REI). My mother was constantly organizing field trips for me and my friends: hiking in the Blue Ridge Mountains, biking along the C&O Canal, camping on the Outer Banks of North Carolina. The thing is, it's not like she would just drop us off and tell us to “enjoy the nature.” No, she was hiking and biking and camping right alongside us. Her own peers thought she was nuts.

Without spending much of her very limited funds (I wouldn't own a video game console or subscribe to cable television until I graduated college in 1999), my mother concocted activity after activity to engage my mind and body. She enrolled me in the DC Youth Orchestra Program, where I learned to play bass and performed at the Kennedy Center and in Knoxville, Tennessee. She enrolled me in tae kwon do after some kids jumped me and stole my bike. She enlisted (yes, enlisted) me in an all-black Boy Scout troop, the highlight of which wasn't the camping trips but rather the field trip we took to a DC Masonic temple, where we grilled the tour guide on the Masons' liberal use of African symbols, all of which he denied.

Under my mother's tutelage, I was becoming a miniature black activist myself. When I was eight, she gave me a book about apartheid, because, you know, how else am I supposed to learn how the world really works? She made me learn all the countries in Africa and quizzed me on them using a map on the wall of her bedroom. I accompanied her to community organizing meetings and stop-the-violence vigils and black cultural festivals on a regular basis.

My mother's parenting strategy was consciously designed to pass on the lessons she'd learned in her life. For example, unlike her own mother, she encouraged spiritual belief but religious flexibility. When I decided to switch from the Catholic church four blocks away to the Episcopal church across the street merely because it was closer, she was fine with that. She just insisted that I be part of

some

community. The

QUESTION AUTHORITY

bumper sticker that would grace my lockers and notebooks from seventh through twelfth grade is one she gave me, always reminding me that just because someone has authority over me does not mean they deserve my respect. This was clearly counter to the programming she'd received in her own upbringing, and she was determined to break the cycle.