How to Read a Paper: The Basics of Evidence-Based Medicine (45 page)

Read How to Read a Paper: The Basics of Evidence-Based Medicine Online

Authors: Trisha Greenhalgh

45

Bate P, Robert G, Bevan H. The next phase of healthcare improvement: what can we learn from social movements?

Quality and Safety in Health Care

2004;

13

(1):62–6.

46

Pope C. Resisting evidence: the study of evidence-based medicine as a contemporary social movement.

Health

2003;

7

(3):267–82.

47

Appleby J, Walshe K, Ham C, et al.

Acting on the evidence: a review of clinical effectiveness—sources of information, dissemination and implementation

. NHS Confederation, Leeds, 1995.

48

Davies HT, Nutley SM. Developing learning organisations in the new NHS.

BMJ: British Medical Journal

2000;

320

(7240):998.

49

Senge PM. The fifth discipline.

Measuring Business Excellence

1997;

1

(3):46–51.

50

Rotter T, Kinsman L, James E, et al. Clinical pathways: effects on professional practice, patient outcomes, length of stay and hospital costs.

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews

(Online) 2010;

3

(3).

Chapter 16

Applying evidence with patients

The patient perspective

There is no such thing as

the

patient perspective—and that is precisely the point of this chapter. At times in our lives, often more frequently the older we get, we are all patients. Some of us are also health professionals—but when the decision relates to

our

health,

our

medication,

our

operation, the side effects that

we

may or may not experience with a particular treatment, we look on that decision differently from when we make the same kind of decision in our professional role.

As you will know by now if you have read the earlier chapters of this book, evidence-based medicine (EBM) is mainly about using some kind of population average—an odds ratio, a number needed to treat, an estimate of mean effect size, and so on—to inform decisions. But very few of us will behave exactly like the point average on the graph: some will be more susceptible to benefit and some more susceptible to harm from a particular intervention. And few of us will value a particular outcome to the same extent as a group average on (say) a standard gamble question (see section ‘How can we help ensure that evidence-based guidelines are followed?’).

The individual unique experience of being ill (or indeed being ‘at risk’ or classified as such) can be expressed in narrative terms: that is, a story can be told about it. And everyone's story is different. The ‘same’ set of symptoms or piece of news will have a host of different meanings depending on who is experiencing them and what else is going on in their lives. The exercise of taking a history from a patient is an attempt to ‘tame’ this individual, idiosyncratic set of personal experiences and put it into a more or less standard format to align with the protocols for assessing, treating and preventing disease. Indeed, England's first professor of general practice, Marshall Marinker [1], once said that the role of medicine is to distinguish the clear message of the disease from the interfering noise of the patient as a person.

As I have written elsewhere, an EBM perspective on

disease

and the patient's unique perspective on his or her

illness

(‘narrative-based medicine’, if you like) are not at all incompatible [2].

It is worth going back to the original definition of EBM proposed by Sackett and colleagues. This definition is reproduced in full, although only the first sentence is generally quoted.

Evidence based medicine is the conscientious, explicit, and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of individual patients. The practice of evidence based medicine means integrating individual clinical expertise with the best available external clinical evidence from systematic research. By individual clinical expertise we mean the proficiency and judgment that individual clinicians acquire through clinical experience and clinical practice. Increased expertise is reflected in many ways, but especially in more effective and efficient diagnosis and in the more thoughtful identification and compassionate use of individual patients' predicaments, rights, and preferences in making clinical decisions about their care. By best available external clinical evidence we mean clinically relevant research, often from the basic sciences of medicine, but especially from patient centred clinical research into the accuracy and precision of diagnostic tests (including the clinical examination), the power of prognostic markers, and the efficacy and safety of therapeutic, rehabilitative, and preventive regimens

(p. 71).

Thus, while the original protagonists of EBM are sometimes wrongly depicted as having airbrushed the poor patient out of the script, they were actually very careful to depict EBM as being contingent on patient choice (and, incidentally, as dependent on clinical judgement). The ‘best’ treatment is not necessarily the one shown to be most efficacious in randomised controlled trials but the one that fits a particular set of individual circumstances and aligns with the patient's preferences and priorities.

The ‘evidence-based’ approach is sometimes stereotypically depicted by the clinician who feels, for example, that every patient with a transient ischaemic attack should take warfarin because this is the most efficacious preventive therapy, whether or not the patients say they don't want to take tablets, can't face the side effects or feel that attending for a blood test every week to check their clotting function is not worth the hassle. A relative of mine was reluctant to take warfarin, for example, because she had been advised to stop eating grapefruit—a food she has enjoyed for breakfast for over 60 years but which contains chemicals that may interact with warfarin. I was pleased that her general practitioner (GP) invited her to come in and discuss the pros and cons of the different treatment options, so that her choice would an informed one.

Almost all research in the EBM tradition between 1990 and 2010 focused on the epidemiological component and sought to build an evidence base of randomised controlled trials and other ‘methodologically robust’ research designs. Later, a tradition of ‘evidence-based patient choice’ emerged in which the patient's right to choose the option most appropriate and acceptable to them was formalised and systematically studied [3]. The third component of EBM referred to in the quote—individual clinical judgement—has not been extensively theorised by scholars within the EBM tradition, although I have written about it myself [4].

PROMs

Before we get into how to involve patients in individualising the decisions of EBM, I want to introduce a relatively new approach to selecting the outcome measures used in clinical trials: patient-reported outcome measures or PROMs. Here's a definition.

PROM's are the tools we use to gain insight from the perspective of the patient into how aspects of their health and the impact the disease and its treatment are perceived to be having on their lifestyle and subsequently their quality of life (QoL). They are typically self-completed questionnaires, which can be completed by a patient or individual about themselves, or by others on their behalf

[5].

By ‘outcome measure’ I mean the aspect of health or illness that researchers choose to measure to demonstrate (say) whether a treatment has been effective. Death is an outcome measure. So is blood pressure. So is the chance of leaving hospital with a live baby when you go into hospital in labour. So is the ability to walk upstairs or make a cup of tea on your own. I could go on—but the point is that in any study the researchers have to define what it is they are trying to influence.

PROMs are not individualised measures. On the contrary, they are still a form of population average, but unlike most outcome measures, they are an average of what matters most to patients rather than an average of what researchers or clinicians felt they ought to measure. The way to develop a PROM is to undertake an extensive phase of qualitative research (see Chapter 12) with a representative sample of people who have the condition you are interested in, analyse the qualitative data and then use it to design a survey instrument (‘questionnaire’, see Chapter 13) that captures all the key features of what patients are concerned about [6] [7].

PROMs were (I believe) first popularised by a team in Oxford led by Ray Fitzpatrick, who used the concept to develop measures for assessing the success of hip and knee replacement surgery [8]. They are now used fairly routinely in many clinical topics in the wider field of ‘outcomes research’ [9] [10]; and a recent monograph by the UK Kings Fund recommends their routine use in National Health Service decision-making [11]. Just as this edition went to press, the

Journal of the American Medical Association

published a set of standards for PROMs [12].

Shared decision-making

Important though PROMs are, they only tell us what patients, on average, value most, not what the patient in front of us values most. To find that out, as I said back in Chapter 1, you would have to ask the patient. And there is now a science and a methodology for ‘asking the patient’ [3] [13].

The science of shared decision-making began in the late 1990s as a quirky interest of some keen academic GPs, notably Elwyn and Edwards [14]. The idea is based on the notion of the patient as a rational chooser, able and willing (perhaps with support) to join in the deliberation over options and make an informed choice.

One challenge is maintaining equipoise—that is, holding back on what you feel the course of action should be and setting out the different options with the pros and cons presented objectively, so the patients can make their own decision [15]. Box 16.1 lists the competencies that clinicians need to practise shared decision-making with their patients [16].

Box 16.1 Competencies for shared decision-making (see reference [14])

Define the problem

—clear specification of the problem that requires a decision.

Portray equipoise

—that professionals may not have a clear preference about which treatment option is the best in the context.

Portray options

—one or more treatment options and the option of no treatment if relevant.

Provide information in preferred format

—identify patients' preferences if they are to be useful to the decision-making process.

Check understanding

—of the range of options and information provided about them.

Explore ideas, concerns and expectations

about the clinical condition, possible treatment options and outcomes.

Checking role preference

—that patients accept the process and identify their decision-making role preference.

Decision-making

—involving the patient to the extent they desire to be involved.

Deferment if necessary

—reviewing treatment needs and preferences after time for further consideration, including with friends or family members, if the patient requires.

Review arrangements

—a specified time period to review the decision.

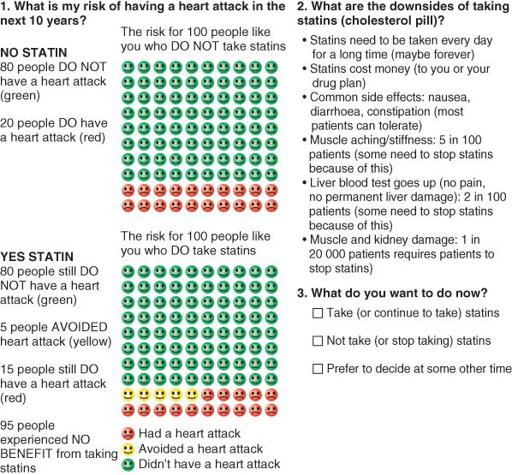

The various instruments and tools to support shared decision-making have evolved over the years. At the very least, a decision aid would have a way of making the rather dry information of EBM more accessible to a non-expert, for example by turning numerical data into diagrams and pictures [17]. An example, shown in

Figure 16.1

, uses colours and simple icons to convey quantitative estimates of risk [18]. The ways of measuring the extent to which patients have been involved in a decision have also evolved [19].

Figure 16.1

Example of a decision aid: choosing statin in a diabetes patient with a 20% risk of myocardial infarction.

Source: Reproduced from reference 18.

Coulter and Collins [20] have produced an excellent guide called

Making Shared Decision-Making a Reality

, which sets out the characteristics of a really good decision aid (Box 16.2).