How to Read a Paper: The Basics of Evidence-Based Medicine (6 page)

Read How to Read a Paper: The Basics of Evidence-Based Medicine Online

Authors: Trisha Greenhalgh

Looking for answers

implies a much more focused approach, a search for an answer we can trust to apply directly to the care of a patient. When we find that trustworthy information, it is OK to stop looking—we don't need to beat the bush for absolutely every study that may have addressed this topic. This kind of query is increasingly well served by new synthesised information sources whose goal is to support evidence-based care and the transfer of research findings into practice. This is discussed further here.

Surveying the literature

—preparing a detailed, broad-based and thoughtful literature review, for example, when writing an essay for an assignment or an article for publication—involves an entirely different process. The purpose here is less to influence patient care directly than to identify the existing body of research that has addressed a problem and clarify the gaps in knowledge that require further research. For this kind of searching, a strong knowledge of information resources and skill in searching them are fundamental. A simple PubMed search will not suffice. Multiple relevant databases need to be searched systematically, and citation chaining (see subsequent text) needs to be employed to assure that no stone has been left unturned. If this is your goal, you

must

consult with an information professional (health librarian, clinical informationist, etc.).

Levels upon levels of evidence

The term

level of evidence

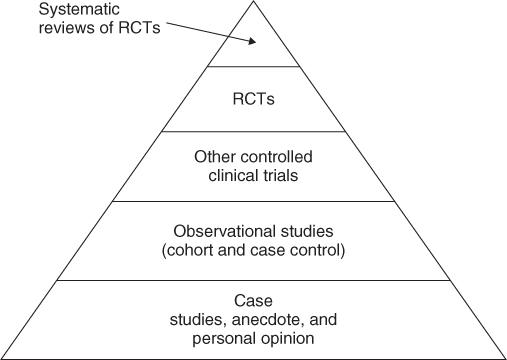

refers to what degree that information can be trusted, based on study design. Traditionally, and considering the commonest type of question (relating to therapy), levels of evidence are represented as a pyramid with systematic reviews positioned grandly at the top, followed by well-designed randomised controlled trials, then observational studies such as cohort studies or case–control studies, with case studies, bench (laboratory) studies and ‘expert opinion’ somewhere near the bottom (

Figure 2.1

). This traditional hierarchy is described in more detail in section ‘The traditional hierarchy of evidence’.

Figure 2.1

A simple hierarchy of evidence for assessing the quality of trial design in therapy studies.

My librarian colleagues, who are often keen on synthesised evidence and technical resources for decision support, remind me of a rival pyramid, with computerised decision support systems at the top, above evidence-based practice guidelines, followed by systematic review synopses, with standard systematic reviews beneath these, and so on [3].

Whether we think in terms of the first (traditional) evidence pyramid or the second (more contemporary) one, the message is clear: all evidence, all information, is not necessarily equivalent. We need to keep a sharp eye out for the believability of whatever information we find, wherever we find it.

Synthesised sources: systems, summaries and syntheses

Information resources synthesised from primary studies constitute a very high level of evidence indeed. These resources exist to help translate research into practice and inform clinician and patient decision-making. This kind of evidence is relatively new (at least, compared to traditional primary research studies, which have been with us for centuries), but their use is expected to grow considerably as they become better known.

Systematic reviews

are perhaps the oldest and best known of the synthesised sources, having started in the 1980s under the inspiration of Archie Cochrane, who bemoaned the multiplicity of individual clinical trials whose information failed to provide clear messages for practice. The original efforts to search broadly for clinical trials on a topic and pool their results statistically grew into the Cochrane Library in the mid-1990s; Cochrane Reviews became the gold standard for systematic reviews and the Cochrane Collaboration the premier force for developing and improving review methodology [4].

There are many advantages to systematic reviews and a few cautions. On the plus side, systematic reviews are relatively easy to interpret. The systematic selection and appraisal of the primary studies according to an approved protocol means that bias is minimised. Smaller studies, which are all too common in some topic areas, may show a trend towards positive impact but lack statistical significance. But when data from several small studies are summed mathematically in a process called

meta-analysis

, the combined data may produce a statistically significant finding (see section ‘Meta-analysis for the non-statistician’). Systematic reviews can help resolve contradictory findings among different studies on the same question. If the systematic review has been properly conducted, the results are likely to be robust and generalisable. On the negative side, systematic reviews can replicate and magnify flaws in the original studies (e.g. if all the primary studies considered a drug at sub-therapeutic dose, the overall—misleading—conclusion may be that the drug has ‘no effect’). Cochrane Reviews can be a daunting read, but here's a tip. The bulk of a Cochrane Review consists of methodological discussion: the gist of it can be gleaned by jumping to the ‘Plain Language Summary’, always to be found directly following the abstract. Alternatively, you can gain a quick and accurate summary by looking at the pictures—especially something called a

forest plot

, which graphically displays the results of each of the primary studies along with the combined result. Chapter 9 explains systematic reviews in more detail.

Cochrane Reviews are only published electronically, but other systematic reviews appear throughout the clinical literature. They are most easily accessed via the Cochrane Library, which publishes Cochrane Reviews, DARE (Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects, listed in Cochrane Library as ‘Other reviews’), and a database of Health Technology Assessments (HTAs). DARE provides not only a bibliography of systematic reviews but also a critical appraisal of most of the reviews included, making this a ‘pre-appraised source’ for systematic reviews. HTAs are essentially systematic reviews but range further to consider economic and policy implications of drugs, technologies and health systems. All may be searched relatively simply and simultaneously via the Cochrane Library.

In the past, Cochrane Reviews focused mainly on questions of therapy (see Chapter 6) or prevention, but since 2008, considerable effort has gone into producing systematic reviews of diagnostic tests (see Chapter 8).

Point-of-care resources

are rather like electronic textbooks or detailed clinical handbooks, but explicitly evidence-based, continuously updated and designed to be user-friendly—perhaps, the textbook of the future. Three popular ones are

Clinical Evidence

,

DynaMed

and

American College of Physicians Physicians' Information and Education Resource

(

ACP PIER

). All of these aspire to be firmly evidence-based, peer-reviewed, revised regularly and with links to the primary research incorporated into their recommendations.

- Clinical Evidence

(

http://clinicalevidence.bmj.com

), a British resource, draws on systematic reviews to provide very quick information, especially on the comparative value of tests and interventions. Reviews are organised into sections, such as Child Health or Skin Disorders; or you can search them by keyword (e.g. ‘asthma’) or by a full review list. The opening page of a chapter lists questions about the effectiveness of various interventions and flags using gold, white or red medallions to indicate whether the evidence for these is positive, equivocal or negative. - DynaMed

(

http://www.ebscohost.com/dynamed

/), produced in the USA, is rather more like a handbook with chapters covering a wide variety of disorders, but with summaries of clinical research, levels of evidence and links to the primary articles. It covers causes and risks, complications and associated conditions (including differential diagnosis), what to look for in the history and physical examination, what diagnostic tests to do, prognosis, treatment, prevention and screening and links to patient information handouts. You can search very simply for the condition: the results include links to other chapters about similar conditions. This is a proprietary resource (i.e. you generally have to pay for it), although it may be provided free to those who offer to write a chapter themselves! - ACP PIER

(

American College of Physicians Physicians' Information and Education Resource

—

http://pier.acponline.org

) is another US source. It uses the standard format of broad recommendation, specific recommendation, rationale and evidence, ACP PIER covers prevention, screening, diagnosis, consultation, hospitalization, drug and non-drug treatments and follow-up. Links to the primary literature are provided and a ‘Patient information’ tab provides links to websites patients would find helpful and authoritative.

Both PIER and DynaMed have applications facilitating use on personal digital assistants (PDAs) or other hand-held devices, which improve their bedside usability for patient care.

New point-of-care resources are continually emerging, so it is very much a matter of individual preference which you use. The three listed were chosen because they are peer-reviewed, regularly updated and directly linked to the primary evidence.

Practice Guidelines

, covered in detail in Chapter 10, are ‘systematically developed statements to assist practitioner and patient decisions about appropriate healthcare for specific clinical circumstances’ [5]. In a good guideline, the scientific evidence is assembled systematically, the panel developing the guideline includes representatives from all relevant disciplines, including patients, and the recommendations are explicitly linked to the evidence from which they are derived [6]. Guidelines are a summarised form of evidence, very high on the hierarchy of pre-appraised resources, but the initial purpose of the guideline should always be kept in mind: guidelines for different settings and different purposes can be based on the same evidence but come out with different recommendations.

Guidelines are readily available from a variety of sources, including the following.

- National Guideline Clearinghouse

(

http://www.guideline.gov

/) is an initiative of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Although a government-funded US database, National Geographic Channel (NGC) is international in content. An advantage of this resource is that different guidelines purporting to cover the same topic can be directly compared on all points, from levels of evidence to recommendations. All guidelines must be current and revised every 5 years. - National Institute for Health and Care Excellence

(

NICE

,

http://www.nice.org.uk

/) is a UK-government-funded agency responsible for developing evidence-based guidelines and other evidence summaries to support national health policy. NICE Clinical Knowledge Summaries (

http://cks.nice.org.uk

) are designed especially for those working in primary healthcare.

A straightforward and popular way to search practice guidelines is via TRIP (Turning Research into Practice,

http://www.tripdatabase.com

), a federated search engine discussed subsequently. For guidelines, look in the box panel to the right of the screen following a simple search: a heading ‘guidelines’ appears, with subheadings for Australian and New Zealand, Canadian, UK, USA and Other, and a number indicting the number of guidelines found on that topic. NICE and National Guideline Clearinghouse are included among the guidelines searched.

Pre-appraised sources: synopses of systematic reviews and primary studies

If your topic is more circumscribed than those covered in the synthesised or summary sources we have explored, or if you are simply browsing to keep current with the literature, consider one of the pre-appraised sources as a means of navigating through those millions of articles in our information jungle. The most common format is the digest of clinical research articles gleaned from core journals and deemed to provide important information for patient care:

Evidence-Based Medicine, ACP Journal Club, Evidence-Based Mental Health

,

POEMS (Patient-Oriented Evidence that Matters)

. Some are free, some are available through institutions or memberships or private subscription. All of them have a format that includes a structured abstract and a brief critical appraisal of the article's content. Studies included may be single studies or systematic reviews. Each is considered a pre-appraised source, and critical appraisal aside, simple inclusion has implications for the perceived quality and importance of the original article.