Hyperspace (12 page)

Authors: Michio Kaku,Robert O'Keefe

Art historian Linda Dalrymple Henderson, writing in

The Fourth Dimension and Non-Euclidean Geometry in Modern Art

, elaborates on this and argues that the fourth dimension crucially influenced the development of Cubism and Expressionism in the art world. She writes that “it was among the Cubists that the first and most coherent art theory based on the new geometries was developed.”

4

To the avant garde, the fourth dimension symbolized the revolt against the excesses of capitalism. They saw its oppressive positivism and vulgar materialism as stifling creative expression. The Cubists, for example, rebelled against the insufferable arrogance of the zealots of science whom they perceived as dehumanizing the creative process.

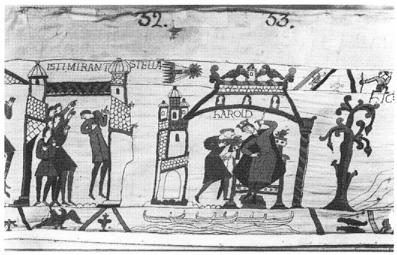

Figure 3.3. One scene in the Bayeux Tapestry depicts frightened English troops pointing to an apparition in the sky (Halley’s comet). The figures are flat, as in most of the art done in the Middle Ages. This signified that God was omnipotent. Pictures were thus drawn two dimensionally. (Giraudon/Art Resource)

The avant garde seized on the fourth dimension as their vehicle. On the one hand, the fourth dimension pushed the boundaries of modern science to their limit. It was more scientific than the scientists. On the other hand, it was mysterious. And flaunting the fourth dimension tweaked the noses of the stiff, know-it-all positivists. In particular, this took the form of an artistic revolt against the laws of perspective.

In the Middle Ages, religious art was distinctive for its deliberate lack of perspective. Serfs, peasants, and kings were depicted as though they were flat, much in the way children draw people. These paintings largely reflected the church’s view that God was omnipotent and could therefore see all parts of our world equally. Art had to reflect his point of view, so the world was painted two dimensionally. For example, the famous Bayeux Tapestry (

Figure 3.3

) depicts the superstitious soldiers of King Harold II of England pointing in frightened wonder at an ominous comet soaring overhead in April 1066, convinced that it is an omen of impending defeat. (Six centuries later, the same comet would be christened Halley’s comet.) Harold subsequently lost the crucial Battle of Hastings to William the Conqueror, who was crowned the king of England, and a new chapter in English history began. However, the Bayeux Tapestry, like other medieval works of art, depicts Harold’s soldiers’ arms and faces as flat, as though a plane of glass had been placed over their bodies, compressing them against the tapestry.

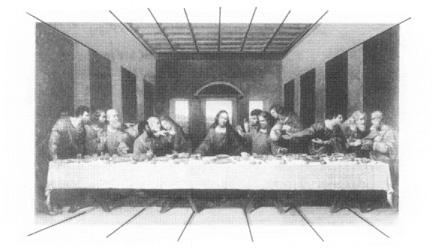

Figure 3.4. During the Renaissance, painters discovered the third dimension. Pictures were painted with perspective and were viewed from the vantage point of a single eye, not God’s eye. Note that all the lines in Leonardo da Vinci’s fresco

The Last Supper

converge to a point at the horizon. (Bettmann Archive)

Renaissance art was a revolt against this flat God-centered perspective, and man-centered art began to flourish, with sweeping landscapes and realistic, three-dimensional people painted from the point of view of a person’s eye. In Leonardo da Vinci’s powerful studies on perspective, we see the lines in his sketches vanishing into a single point on the horizon. Renaissance art reflected the way the eye viewed the world, from the singular point of view of the observer. In Michelangelo’s frescoes or in da Vinci’s sketch book, we see bold, imposing figures jumping out of the second dimension. In other words, Renaissance art discovered the third dimension (

Figure 3.4

).

With the beginning of the machine age and capitalism, the artistic world revolted against the cold materialism that seemed to dominate

industrial society. To the Cubists, positivism was a straitjacket that confined us to what could be measured in the laboratory, suppressing the fruits of our imagination. They asked: Why must art be clinically “realistic”? This Cubist “revolt against perspective” seized the fourth dimension because it touched the third dimension from all possible perspectives. Simply put, Cubist art embraced the fourth dimension.

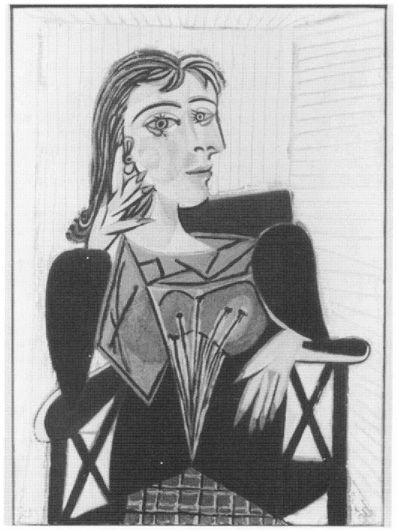

Picasso’s paintings are a splendid example, showing a clear rejection of the perspective, with women’s faces viewed simultaneously from several angles. Instead of a single point of view, Picasso’s paintings show multiple perspectives, as though they were painted by someone from the fourth dimension, able to see all perspectives simultaneously (

Figure 3.5

).

Picasso was once accosted on a train by a stranger who recognized him. The stranger complained: Why couldn’t he draw pictures of people the way they actually were? Why did he have to distort the way people looked? Picasso then asked the man to show him pictures of his family. After gazing at the snapshot, Picasso replied, “Oh, is your wife really that small and flat?” To Picasso, any picture, no matter how “realistic,” depended on the perspective of the observer.

Abstract painters tried not only to visualize people’s faces as though painted by a four-dimensional person, but also to treat time as the fourth dimension. In Marcel Duchamp’s painting

Nude Descending a Staircase

, we see a blurred representation of a woman, with an infinite number of her images superimposed over time as she walks down the stairs. This is how a four-dimensional person would see people, viewing all time sequences at once, if time were the fourth dimension.

In 1937, art critic Meyer Schapiro summarized the influence of these new geometries on the art world when he wrote, “Just as the discovery of non-Euclidean geometry gave a powerful impetus to the view that mathematics was independent of existence, so abstract painting cut at the roots of the classic ideas of artistic imitation.” Or, as art historian Linda Henderson has said, “the fourth dimension and non-Euclidean geometry emerge as among the most important themes unifying much of modern art and theory.”

5

The fourth dimension also crossed over into Czarist Russia via the writings of the mystic P. D. Ouspensky, who introduced Russian intellectuals to its mysteries. His influence was so pronounced that even Fyodor Dostoyevsky, in

The Brothers Karamazov

, had his protagonist Ivan Karamazov speculate on the existence of higher dimensions and non-Euclidean geometries during a discussion on the existence of God.

Figure 3.5. Cubism was heavily influenced by the fourth dimension. For example, it tried to view reality through the eyes of a fourth-dimensional person. Such a being, looking at a human face, would see all angles simultaneously. Hence, both eyes would be seen at once by a fourth-dimensional being, as in Picasso’s painting

Portrait of Dora Maar. (

Giraudon/Art Resource

. ©

1993. Ars, New York/Spadem, Paris)

Because of the historic events unfolding in Russia, the fourth dimension was to play a curious role in the Bolshevik Revolution. Today, this strange interlude in the history of science is important because Vladimir Lenin would join the debate over the fourth dimension, which would eventually exert a powerful influence on the science of the former Soviet Union for the next 70 years.

6

(Russian physicists, of course, have played key roles in developing the present-day ten-dimensional theory.)

After the Czar brutally crushed the 1905 revolution, a faction called the Otzovists, or “God-builders,” developed within the Bolshevik party. They argued that the peasants weren’t ready for socialism; to prepare them, Bolsheviks should appeal to them through religion and spiritualism. To bolster their heretical views, the God-builders quoted from the work of the German physicist and philosopher Ernst Mach, who had written eloquently about the fourth dimension and the recent discovery of a new, unearthly property of matter called radioactivity. The God-builders pointed out that the discovery of radioactivity by the French scientist Henri Becquerel in 1896 and the discovery of radium by Marie Curie in 1896 had ignited a furious philosophical debate in French and German literary circles. It appeared that matter could slowly disintegrate and that energy (in the form of radiation) could reappear.

Without question, the new experiments on radiation showed that the foundation of Newtonian physics was crumbling. Matter, thought by the Greeks to be eternal and immutable, was now disintegrating before our very eyes. Uranium and radium, confounding accepted belief, were mutating in the laboratory. To some, Mach was the prophet who would lead them out of the wilderness. However, he pointed in the wrong direction, rejecting materialism and declaring that space and time were products of our sensations. In vain, he wrote, “I hope that nobody will defend ghost-stories with the help of what I have said and written on this subject.”

7

A split developed within the Bolsheviks. Their leader, Vladimir Lenin, was horrified. Are ghosts and demons compatible with socialism? In exile in Geneva in 1908, he wrote a mammoth philosophical tome,

Materialism and Empirio-Criticism

, defending dialectical materialism from the onslaught of mysticism and metaphysics. To Lenin, the mysterious disappearance of matter and energy did not prove the existence of spirits. He argued that this meant instead that a

new dialectic

was emerging, which would embrace both matter and energy. No longer could they be

viewed as separate entities, as Newton had done. They must now be viewed as two poles of a dialectical unity. A new conservation principle was needed. (Unknown to Lenin, Einstein had proposed the correct principle 3 years earlier, in 1905.) Furthermore, Lenin questioned Mach’s easy embrace of the fourth dimension. First, Lenin praised Mach, who “has raised the very important and useful question of a space of

n

dimensions as a conceivable space.” Then he took Mach to task for failing to emphasize that only the three dimensions of space could be verified experimentally. Mathematics may explore the fourth dimension and the world of what is possible, and this is good, wrote Lenin, but the Czar can be overthrown only in the third dimension!

8

Fighting on the battleground of the fourth dimension and the new theory of radiation, Lenin needed years to root out Otzovism from the Bolshevik party. Nevertheless, he won the battle shortly before the outbreak of the 1917 October Revolution.

Eventually, the ideas of the fourth dimension crossed the Atlantic and came to America. Their messenger was a colorful English mathematician named Charles Howard Hinton. While Albert Einstein was toiling at his desk job in the Swiss patent office in 1905, discovering the laws of relativity, Hinton was working at the United States Patent Office in Washington, D.C. Although they probably never met, their paths would cross in several interesting ways.

Hinton spent his entire adult life obsessed with the notion of popularizing and visualizing the fourth dimension. He would go down in the history of science as the man who “saw” the fourth dimension.

Hinton was the son of James Hinton, a renowned British ear surgeon of liberal persuasion. Over the years, the charismatic elder Hinton evolved into a religious philosopher, an outspoken advocate of free love and open polygamy, and finally the leader of an influential cult in England. He was surrounded by a fiercely loyal and devoted circle of free-thinking followers. One of his best-known remarks was “Christ was the Savior of men, but I am the savior of women, and I don’t envy Him a bit!”

9