I for Isobel

Â

Â

Â

Â

AMY WITTING was the pen name of Joan Austral Fraser, born on 26 January 1918 in the inner-Sydney suburb of Annandale. After attending Fort Street Girls' High School she studied arts at the University of Sydney.

She married Les Levick, a teacher, in 1948 and they had a son. Witting spent her working life teaching, but began writing seriously while recovering from tuberculosis in the 1950s.

Two stories appeared in the

New Yorker

in the mid-1960s, leading to

The Visit

(1977), an acclaimed novel about small-town life in New South Wales. Two years later Witting completed her masterpiece,

I for Isobel

, which was rejected by publishers troubled by its depiction of a mother tormenting her child.

When

I for Isobel

was eventually published, in 1989, it became a bestseller. Witting was lauded for the power and acuity of her portrait of the artist as a young woman. In 1993 she won the Patrick White Award.

Witting published prolifically in her final decade. After two more novels, her

Collected Poems

appeared in 1998 and her collected stories,

Faces and Voices

, in 2000.

Between these volumes came

Isobel on the Way to the Corner Shop

, the sequel to

I for Isobel

. Both

Isobel

novels were shortlisted for the Miles Franklin Award; the latter was the 2000

Age

Book of the Year.

Amy Witting died in 2001, weeks before her novel

After Cynthia

was published and while she was in the early stages of writing the third

Isobel

book. She was made a Member of the Order of Australia and a street in Canberra bears her name.

Â

Â

Â

CHARLOTTE WOOD has been described by the

Age

as âone of the most intelligent and compassionate novelists in Australia'.

Animal People

, her latest novel, was shortlisted for the Christina Stead Prize and won the People's Choice in the 2013 NSW Premier's Literary Awards. She edits

The Writer's Room Interviews

magazine and is working on her fifth novel.

ALSO BY AMY WITTING

The Visit

Marriages

(stories)

A Change in the Lighting

In and Out the Window

(stories)

Maria's War

Isobel on the Way to the Corner Shop

Faces and Voices

(stories)

After Cynthia

Â

Â

Â

The Text Publishing Company

Swann House

22 William Street

Melbourne Victoria 3000

Australia

Copyright © Amy Witting 1989

Introduction copyright © Charlotte Wood 2014

The moral rights of the authors have been asserted.

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright above, no part of this publication shall be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

First published by Penguin Books Australia 1989

This edition published by The Text Publishing Company 2013

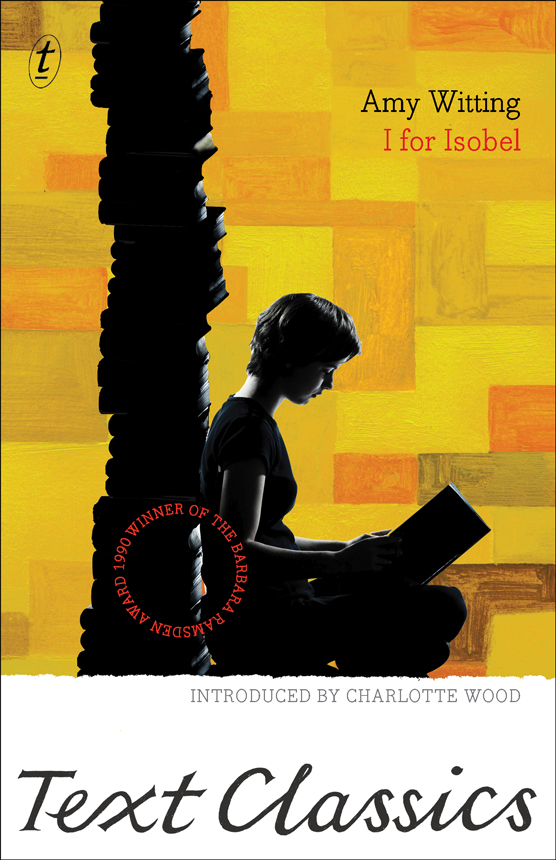

Cover design by WH Chong

Page design by Text

Typeset by Midland Typesetting

Primary print ISBN: 9781922147745

Ebook ISBN: 9781922148742

Author: Witting, Amy, 1918â2001.

Title: I for Isobel / by Amy Witting; introduced by Charlotte Wood.

Series: Text classics.

Dewey Number: A823.3

Â

Â

CONTENTS

Â

A Potent Victory

by Charlotte Wood

Â

A Potent Victory

by Charlotte Wood

FOR a girl, to be hated by your mother is surely the most savage knowledge with which to begin your life. It's this fact that attaches itself to the child protagonist in the opening pages of Amy Witting's best-known novel, and follows her, pitilessly, into adulthood.

I for Isobel

was first published in 1989, the year I began learning to write fiction. I have always known of this book, which stands as one of the landmarks of my literary heritage. Alongside Jessica Anderson and Thea Astley, Witting is a kind of grand aunt to contemporary Australian writers interested in stories of intimate psychological spacesâand in the lives of women.

So why, until this year, had I never read

I for Isobel

and its sequel,

Isobel on the Way to the Corner Shop

? I'd read Park and Stead, Anderson and Astley, Hewett and Jolley, but somehow I never found the time or the inclination for Witting's works. That they were long out of print made it harder, but there must have been some other resistance in me. Only now do I realise, with striking clarity and a little shame, that their titles had turned me off. I confess that even with the obvious picture-book irony, they sounded embarrassing to me: girlish and flatfooted, giving off a cutesy, floral whiff.

How wrong I was.

I for Isobel

opens on Isobel's ninth birthday with her mother's words, the same words she has heard every year of her life: âNo birthday presents this year!' And with that, a dangerous theme of Witting's world is introduced: that there can be a psychic violence in the bonds between women, and it is a violence of which they must never speak.

Conflating life and fiction is always a mistake; Isobel is not Amy. The author maintained a lifelong privacy about her own childhood and mother, making only oblique references to family difficulties. But Isobel's fight for personal, intellectual sovereignty against brutal resistance was familiar to her creator, and there's little doubt that the two novels were Witting's exploration of what Flaubert called âthe deep and always hidden wound'.

In one sense

I for Isobel

is a simple coming-of-age story: the tale of Isobel Callaghan, who must pretend to be nicer, stupider, duller than she is, because the reality of what she isâintellectually gifted, powerfully desiringâis a threat not only to her family but to society itself.

It's a small, pinched society that emerges, spreading out from Isobel's family to the wider world, the city of Sydney and Australia as a whole. At the start, even on holidays, Isobel is forbidden from reading in bed. As solace for the lack of any celebration (âIt is vulgar to celebrate birthdays away from home,' Mrs Callaghan says, as she does every January), Isobel finds

The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes

on the guesthouse bookshelves, and disappears into it. But she knows this pleasure is suspect; it must remain private, a hidden celebration.

Here is the novel's other great theme: redemption through the written word. Isobel's struggle to be allowed to read in peace is repeated again and again, well into adulthoodâat home, then as a young woman living and working in the inner city. Unpacking her books in her single room, Isobel thinks she breathes the air of freedom, but soon learns better. Forbidden from staying in her room (electricity costs!), she takes to a corner of the sitting room, where her bridge-playing fellow boarders are as insulted by her reading as her office workmates are affronted by any sign of independent thought. (In

Isobel on the Way to the Corner Shop

, her roommate in the tuberculosis sanatorium responds to Isobel's peaceful reading with cries of pure rage.)

From childhood, Isobel's struggle for the mental privacy and the spaciousness of literature is a battle for the right to thinkâand to endure. Whatever other punishments she tolerates for being a girl with a brain, she will not give up books. They are talismans and religion; they are solidity, survival, and, at last, liberty.

Her mother's hatred is commonplace and devastating. It manifests not in physical violence but in dismissal and disregard, in horrible childish competitiveness, and the scoring of petty points so transparently vindictive that even nine-year-old Isobel can empathise with the infant in her mother. When Mrs Callaghan's spitefulness is singled out by the other adult holidaymakers, stunning her into a moment's humiliation, Isobel âfelt an ache of sympathy, knowing how it felt to be the last to be chosen, or even left out of the game'. Soon the child discovers that her mother's greatest fear is Isobel's own hard-won composure under fire.

âTell me.' Her mother's voice, which had been rising to a scream, turned calm and gracious again. Like somebody getting dressed. Isobel looked up and saw that her eyes were frantic bright. She doesn't want me to tell her, she wants me to scream. I do something for her when I scream.

Then she saw that her mother's anger was a live animal tormenting her, that she Isobel was an outlet that gave some relief and she was torturing her by withholding it.

This portrayal of a child's guilt and sympathy for a loveless parent is compelling because it rings true. Distressing as it may be to those of us with loving mothers, still we recognise its veracity. For those with Isobel's kind of mother, there is a depthless relief in having brute reality shaped into art, having darkness brought into light. It is the relief of hearing the clear and unashamed statement of the unspeakable: not all mothers love their children. Perhaps even worse, some mothers love some of their children and not others.

But telling the truth, even in fiction, is dangerousâand part of this novel's story is the story of its rejection. Witting's first novel,

The Visit

, was published in 1977 to good reviews. She finished

I for Isobel

in 1979, the start of feminism's flourishing years. It was accepted by her publisher, then âunaccepted' for being too dark, too weird. The highly respected editor Beatrice Davis rejected it with the words, âNo mother has ever behaved so badly to her own child.' A gobsmacking claim, and one that speaks of a sexism still at large in the myth of feminine virtue.

Other rejections followed and, despite Witting being the only Australian short-fiction writer to be twice published by the

New Yorker

, her novel lay unpublished for a decade. When it was finally released it became an instant bestseller and was shortlisted for the Miles Franklin Award (many felt it should have won). Witting was seventy-one. Between then and her death at eighty-three she published

four more novels

, as well as story collections and books of poetry.

But Witting had been writing all her life. Born Joan Fraser, then marrying as Joan Levick, she spent her years at Sydney University as an intimate of the poet James McAuley and his circle, saying later, âI spent my life trying to emerge from that group.' She adopted the pseudonym Amy Wittingâa sly rebuttal of society's preference for naive young women, and a promise to herself to âalways be witting'âbut literary success eluded her, and she spent most of her working life as a gifted and beloved teacher.