I Have Landed (49 page)

Authors: Stephen Jay Gould

As his putatively strongest refutation of Darwinism, Behe cites the ersatz version of Richardson's work on Haeckel's drawings. (Behe presents only two other arguments, one that he accepted as true [the evolution of antibiotic resistance by several bacterial strains], the second judged as “unsupported by current evidence” [the “classic” case of industrial melanism in moths], with only this third pointâthe tale of Haeckel's drawingsâdeclared “downright false.” So if this piece represents Behe's best shot, I doubt that creationists will receive much of a boost from their latest academic poster boy.) Behe writes:

The story of the embryos is an object lesson in seeing what you want to see. Sketches of vertebrate embryos were first made in the last 19th century by Ernst Haeckel, an admirer of Darwin. In the intervening years, apparently nobody verified the accuracy of Haeckel's drawings . . . If supposedly identical embryos were once touted as strong evidence for evolution, does the recent demonstration of variation in embryos now count as evidence against evolution?

From this acme of media hype and public confusion, we should step back and reassert the two crucial points that accurately site Haeckel's drawings as a poignant and fascinating historical tale and a cautionary warning about scientific carelessness (particularly in the canonical and indefensible practices of textbook writing)âbut not, in any way, as an argument against evolution, or a sign of weakness in Darwinian theory. Moreover, as a testament to greatness of intellect and love of science, whatever the ultimate validity of an underlying world-view honorably supported by men of such stature, we may look to the work of von Baer and Agassiz, Darwin's most valiant opponents in his own day, for our best illustrations of these two clarifying points.

1.

Haeckel's forgeries as old news

. Tales of scientific fraud excite the imagination for good reason. Getting away with this academic equivalent of murder for generations, and then being outed a century after your misdeeds, makes even better copy. Richardson reexamined Haeckel's drawings for good reasons, and he never claimed that he had uncovered the fraud. But press commentary then invented and promulgated this phony versionâand these particular chickens came home to a creationist roost (do pardon this rather mixed metaphor!).

Haeckel's expert contemporaries recognized what he had done, and said so in print. For example, a famous 1894 article by Cambridge University zoologist Adam Sedgwick (“On the law of development commonly known as von Baer's law”) included the following withering footnote of classical Victorian understatement:

I do not feel called upon to characterise the accuracy of the drawings of embryos of different classes of Vertebrata given by Haeckel in his popular works. . . . As a sample of their accuracy, I may refer the reader to the varied position of the auditory sac in the drawings of the younger embryos.

I must confess to a personal reason, emotional as well as intellectual, for long and special interest in this tidbit of history. Some twenty years ago I found, on the open stacks of our Museum's library, Louis Agassiz's personal copy of the first (1868) edition of Haeckel's

Natürliche Schöpfungsgeschichte

(The Natural History of Creation). After his death, Agassiz's library passed into the museum's general collection, where indifferent librarianship (before the present generation) led to open access, through nonrecognition, for such priceless treasures.

I noted, with the thrill that circumstances vouchsafe to an active scholar only a few times in a full career, that Agassiz had penciled copious marginal notesâsome forty pages' worth in typed transcriptionâinto this copy. But I couldn't read his scribblings. Agassiz, a typical Swiss polyglot, annotated books in the language of their composition. Moreover, when he wrote marginalia into a German book published in Roman type, he composed the notes in Roman script (which I can read and translate). But when he read a German book printed in old, but easily decipherable,

Fraktur

type (as in Haeckel's 1868 edition), he wrote his annotations in the corresponding (and now extinct)

Sütterlin

script (which I cannot read at all). Fortuna, the Roman goddess, then smiled upon me, for my secretary, Agnes Pilot, had been educated in Germany just before the Second World Warâand she,

Gott sei Dank

, could still read this

archaic script. So she transliterated Agassiz's squiggles into readable German in Roman type, and I could finally sense Agassiz's deep anger and distress.

In 1868, Agassiz at age sixty-one, and physically broken by an arduous expedition to Brazil, felt old, feeble, and bypassedâespecially in the light of his continued opposition to evolution. (His own graduate students had all “rebelled” and embraced the new Darwinian model.) He particularly disliked Haeckel for his crass materialism, his scientifically irrelevant and vicious swipes at religion, and his haughty dismissal of earlier work (which he often shamelessly “borrowed” without attribution). And yet, in reading through Agassiz's extensive marginalia, I sensed something noble about the quality of his opposition, however ill-founded in the light of later knowledge.

To be sure, Agassiz waxes bitter at Haeckel's excesses, as in the accompanying figure of his final note appended to the closing flourish of Haeckel's book, including the author's gratuitous attack on conventional religion as “the dark beliefs and secrets of a priestly class.” Agassiz writes sardonically:

Gegeben im Jahre I der neuen Weltordnung. E. Haeckel

. (Given in year one of the new world order. E. Haeckel.) But Agassiz generally sticks to the high road, despite ample provocation, by marshaling the facts of his greatest disciplinary expertise (in geology, paleontology, and zoology) to refute Haeckel's frequent exaggerations and rhetorical inconsistencies. Agassiz may have been exhausted and discouraged, but he could still put up a whale of a fight, even if only in private. (See my previous 1979 publication for details: “Agassiz's later, private thoughts on evolution: his marginalia in Haeckel's

Natürliche Schöpfungsgeschichte (1868),”

in Cecil Schneer, ed.,

History of Geology

[University of New Hampshire: The University Press of New England, 277â82].)

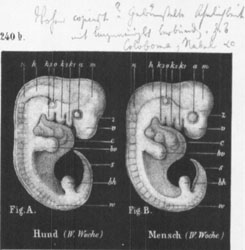

Agassiz proceeded in generally measured prose until he came to page 240, where he encountered Haeckel's falsified drawings of vertebrate embryologyâa subject of extensive personal research and writing on Agassiz's part. He immediately recognized what Haeckel had done, and he exploded in fully justified rage. Above the nearly identical pictures of dog and human embryos, Agassiz wrote:

Woher copiert? Gekünstelte Ãhnlichkeit mit Ungenauigkeit verbunden, z.b. Coloboma, Nabel, etc

. (Where were these copied from? [They include] artistically crafted similarities mixed with inaccuracies, for example, the eye slit, umbilicus, etc.)

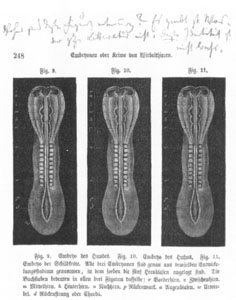

At least these two drawings displayed some minor differences. But when Agassiz came to page 248, he noticed that Haeckel had simply copied the same exact figure three times in supposedly illustrating a still earlier embryonic stage of a dog (left), a chicken (middle), and a tortoise (right). He wrote above this figure:

Woher sind diese Figuren entnommen? Es gibt sowas in der ganzen

Litteratur nicht. Diese Identität ist nicht wahr

. (Where were these figures taken from? Nothing like this exists in the entire literature. This identity is not true.)

Finally, on the next page, he writes his angriest note next to Haeckel's textual affirmation of this threefold identity. Haeckel stated: “If you take the young embryos of a dog, a chicken and a tortoise, you cannot discover a single difference among them.” And Agassiz sarcastically replied:

Natürlichâda diese Figuren nicht nach der Natur gezeichnet, sondern eine von der andern copiert ist! Abscheulich

. (Naturallyâbecause these figures were not drawn from nature, but rather copied one from the other! Atrocious.)

2.

Haeckel's forgeries as irrelevant to the validity of evolution or Darwinian mechanisms

. From the very beginning of this frenzied discussion two years ago, I have been thoroughly mystified as to what, beyond simple ignorance or self-serving design, could ever have inspired the creators of the sensationalized version to claim that Haeckel's exposure challenges Darwinian theory, or even evolution itself. After all, Haeckel used these drawings to support his theory of recapitulationâthe claim that embryos repeat successive adult stages of their ancestry. For reasons elaborated at excruciating length in my book

Ontogeny and Phylogeny

, Darwinian science conclusively disproved and abandoned this idea by 1910 or so, despite its persistence in popular culture. Obviously, neither evolution nor Darwinian theory needs the support of a doctrine so conclusively disconfirmed from within.

I do not deny, however, that the notion of greater embryonic similarity, followed by increasing differentiation toward the adult stages of related forms, has continued to play an important, but scarcely defining, role in biological theory

âbut through the later evolutionary version of another interpretation first proposed by von Baer in his 1828 treatise, one of the greatest works ever published in the history of science. In a pre-evolutionary context, von Baer argued that development, as a universal pattern, must proceed by a process of differentiation from the general to the specific. Therefore, the most general features of all vertebrates will arise first in embryology, followed by a successive appearance of ever more specific characters of particular groups.

Early embryonic stages of dog (left) and human (right), as drawn by Haeckel for an 1868 book, but clearly “fudged” in exaggerating and even making up some of the similarities. Louis Agassiz's copy, with his angry words of commentary at top

.

Agassiz's angry comments (written above) upon Haecfyel's false figure of similarities in the early embryonic stages of dog, chicken, and tortoise. Haeckel simply copied the same drawing three times

.

Agassiz's angry comments on Haeckel's falsified drawings

â

ending with the judgment used as the title for this essay:

“Abscheulich!”

In other words, you can first tell that an embryo will become a vertebrate rather than an arthropod, then a mammal rather than a fish, then a carnivore rather than a rodent, and finally good old Rover rather than Ms. Tabby. Under von Baer's reading, a human embryo grows gill slits not because we evolved

from an adult fish (Haeckel's recapitulatory explanation), but because all vertebrates begin their embryological lives with gills. Fish, as “primitive” vertebrates, depart least from this basic condition in their later development, whereas mammals, as most “advanced,” lose their gills and grow lungs during their maximal embryological departure from the initial and most generalized vertebrate form.

Von Baer's Lawâas biologists soon christened this principle of differentiationâreceived an easy and obvious evolutionary interpretation from Darwin's hand. The intricacies of early development, when so many complex organs differentiate and interconnect in so short a time, allow little leeway for substantial change, whereas later stages with fewer crucial connections to the central machinery of organic function permit greater latitude for evolutionary change. (In rough analogy, you can always paint your car a different color, but you had better not mess with basic features of the internal combustion engine as your future vehicle rolls down the early stages of the assembly line.)