I Have Landed (48 page)

Authors: Stephen Jay Gould

Men of large vision often display outsized foibles as well. No character in the early days of Darwinism can match Haeckel for enigmatic contrast of the admirable and the dubious. No one could equal his energy and the volume of his outputâmost of high quality, including volumes of technical taxonomic description (concentrating on microscopic radiolarians, and on jellyfishes and their allies), not only theoretical effusions. But no major figure took so much consistent liberty in imposing his theoretical beliefs upon nature's observable factuality.

I won't even discuss Haeckel's misuse of Darwinian notions in the service of a strident German nationalism based on claims of cultural, and even biological, superiorityâa set of ideas that became enormously popular and did provide

later fodder for Nazi propagandists (obviously not Haeckel's direct fault, although scholars must bear some responsibility for exaggerated, but not distorted, uses of their argumentsâsee D. Gasman,

The Scientific Origins of National Socialism: Social Darwinism in Ernst Haeckel and the German Monist League

[London: MacDonald, 1972]). Let's consider only his drawings of organisms, supposedly a far more restricted subject, imbued with far less opportunity for any “play” beyond sober description.

I do dislike the common phrase “artistic license,” especially for its parochially smug connotation (when used by scientists) that creative humanists care little for empirical accuracy. (After all, the best artistic “distortions” record great skill and conscious intent, applied for definite and fully appropriate purposes; moreover, when great artists choose to depict external nature as seen through our eyes, they have done so with stunning accuracy.) But I don't know how else to describe Haeckel, who was, by the way, a skilled artist and far more than a Sunday painter.

Haeckel published books at the explicit interface of art and scienceâand here he stated no claim for pure fidelity to nature. His

Kunstformen der Natur

(Artforms of Nature), published in 1904 and still the finest work ever printed in this genre, contains one hundred plates of organisms crowded into intricate geometric arrangements. One can identify the creatures, but their invariably curved and swirling forms so closely follow the reigning conventions of art nouveau (called

Jugendstil

in Germany) that one cannot say whether the plates should be labeled as illustrations of actual organisms or primers for a popular artistic style.

But Haeckel also prepared his own illustrations for his technical monographs and scientific booksâand here he did claim, while standard practice and legitimate convention also required, no conscious departure from fidelity to nature. Yet Haeckel's critics recognized from the start that this master naturalist, and more than competent artist, took systematic license in “improving” his specimens to make them more symmetrical or more beautiful. In particular, the gorgeous plates for his technical monograph on the taxonomy of radiolarians (intricate and delicate skeletons of single-celled planktonic organisms) often “enhanced” the actual appearances (already stunningly complex and remarkably symmetrical) by inventing structures with perfect geometric regularity.

This practice cannot be defended in any sense, but distortions in technical monographs cause minimal damage because such publications rarely receive attention from readers without enough professional knowledge to recognize the fabrications. “Improved” illustrations masquerading as accurate drawings spell much more trouble in popular books intended for general audiences lacking

the expertise to separate a misleading idealization from a genuine signal from nature. And here, in depicting vertebrate embryos in several of his most popular books, Haeckel took a license that subjected him to harsh criticism in his own day and, in a fierce brouhaha (or rather a tempest in a teapot), has resurfaced in the last two years to haunt him (and us) again, and even to give some false comfort to creationists.

We must first understand Haeckel's own motivationsânot as any justification for his actions, but as a guide to a context that has been sadly missing from most recent commentary, thereby leading to magnification and distortion of this fascinating incident in the history of science. Haeckel remains most famous today as the chief architect and propagandist for a famous argument that science disproved long ago, but that popular culture has never fully abandoned, if only because the standard description sounds so wonderfully arcane and mellifluousâ“ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny,” otherwise known as the theory of recapitulation or, roughly, the claim that organisms retrace their evolutionary history, or “climb their own family tree” to cite an old catchphrase, during their embryological development. Thus the gill slits of the early human embryo supposedly repeat our distant ancestral past as a fish, while the transient embryonic tail, developing just afterward, marks the later reptilian phase of our evolutionary ascent. (My first technical book,

Ontogeny and Phylogeny

[Harvard University Press, 1977], includes a detailed account of the history of recapitulationâan evolutionary notion exceeded only by natural selection itself for impact upon popular culture. See essay 8 for a specific, and unusual, expression of this influence in the very different field of psychoanalysis.)

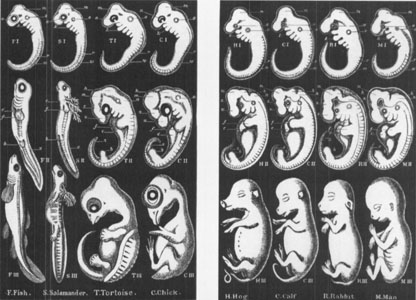

As primary support for his theory of recapitulation, and to advance the argument that all vertebrates may be traced to a common ancestor, Haeckel frequently published striking drawings, showing parallel stages in the development of diverse vertebrates, including fishes, chickens, and several species of mammals from cows to humans. The accompanying figure (on page 310) comes from a late, inexpensive, popular English translation, published in 1903, of his most famous book,

The Evolution of Man

. Note how the latest depicted stages (bottom row) have already developed the distinctive features of adulthood (the tortoise's shell, the chick's beak). But Haeckel draws the earliest stages of the first row, showing tails below and gill slits just under the primordial head, as virtually identical for all embryos, whatever their adult destination. Haeckel could thus claim that this near identity marked the common ancestry of all vertebratesâfor, under the theory of recapitulation, embryos pass through a series of stages representing successive adult forms of their evolutionary history. An identical embryonic stage can only imply a single common ancestor.

To cut to the quick of this drama: Haeckel exaggerated the similarities by idealizations and omissions. He also, in some casesâin a procedure that can only be called fraudulentâsimply copied the same figure over and over again. At certain stages in early development, vertebrate embryos do look more alike, at least in gross anatomical features easily observed with human eyes, than do the adult tortoises, chickens, cows, and humans that will develop from them. But these early embryos also differ far more substantially, one from the other, than Haeckel's figures show. Moreover, Haeckel's drawings never fooled expert embryologists, who recognized his fudgings right from the start.

At this point a relatively straightforward factual story, blessed with a simple moral message as well, becomes considerably more complex, given the foibles and practices of the oddest primate of all. Haeckel's drawings, despite their noted inaccuracies, entered into the most impenetrable and permanent of all quasi-scientific literatures: standard student textbooks of biology. I do not know how the transfer occurred in this particular case, but the general (and highly troubling) principles can be easily identified. Authors of textbooks cannot

be experts in all subdisciplines of their subject. They should be more careful, and they should rely more on primary literature and the testimony of expert colleagues. But shortcuts tempt us all, particularly in the midst of elaborate projects under tight deadlines.

A famous chart of the embryological development of eight different vertebrates, as drawn by Haeckel for a 1903 edition of his popular book

, The Evolution of Man.

Haeckel exaggerated the similarities of the earliest stages (top row) with gill slits and tails

.

Therefore, textbook authors often follow two suboptimal routes that usually yield adequate results, but can also engender serious trouble: they copy from previous textbooks, and they borrow from the most widely available popular sources. No one ever surpassed Haeckel in fame and availability as a Darwinian spokesman who also held high professional credentials as a noted professor at the University of Jena. So textbook authors borrowed his famous drawings of embryonic development, probably quite unaware of their noted inaccuracies and outright falsificationsâor (to be honest about dirty laundry too often kept hidden) perhaps well enough aware, but then rationalized with the ever-tempting and ever-dangerous argument, “Oh well, it's close enough to reality for student consumption, and it does illustrate a general truth with permissible idealization.” (I am a generous realist on most matters of human foibles. But I confess to raging fundamentalism on this issue. The smallest compromise in dumbing down by inaccuracy destroys integrity and places an author upon a slippery slope of no return.)

Once ensconced in textbooks, misinformation becomes cocooned and effectively permanent because, as stated above, textbooks copy from previous texts. (I have written two previous essays on this lamentable practiceâone on the amusingly perennial description of the “dawn horse” eophippus as “fox terrier” in size, even though most authors, including yours truly, have no idea about the dimensions or appearance of this breed; and the other on the persistent claim that elongating giraffe necks provide our best illustration of Darwinian natural selection versus Lamarckian use and disuse, when, in fact, no meaningful data exist on the evolution of this justly celebrated structure.)

We should therefore not be surprised that Haeckel's drawings entered nineteenth-century textbooks. But we do, I think, have the right to be both astonished and ashamed by the century of mindless recycling that has led to the persistence of these drawings in a large number, if not a majority, of modern textbooks! Michael Richardson of the St. George Hospital Medical School in London, a colleague who deserves nothing but praise for directing attention to this old issue, wrote to me (letter of August 16, 1999):

If so many historians knew all about the old controversy [over Haeckel's falsified drawings] then why did they not communicate this information to the numerous contemporary authors who use

the Haeckel drawings in their books? I know of at least fifty recent biology texts which use the drawings uncritically. I think this is the most important question to come out of the whole story.

The recent flap over this more-than-twice-told taleâan almost comical manifestation of the famous dictum that those unfamiliar with history (or simply careless in reporting) must be condemned to repeat the pastâbegan with an excellent technical paper by Richardson and six other colleagues in 1997 (“There is no highly conserved embryonic stage in the vertebrates: implications for current theories of evolution and development,”

Anatomy and Embryology

, volume 196: 91â106; following a 1995 article by Richardson alone in

Developmental Biology

, volume 172: 412â21). In these articles, Richardson and colleagues discussed the original Haeckel drawings, briefly noted the contemporary recognition of their inaccuracies, properly criticized their persistent appearance in modern textbooks, and then presented evidence (discussed below) of the differences in early vertebrate embryos that Haeckel's tactics had covered up, and that later biologists had therefore forgotten. Richardson invoked this historical tale in order to make an important point, also mentioned below, about exciting modern work in the genetics of development.

From this excellent and accurate beginning, the reassertion of Haeckel's old skullduggery soon spiraled into an abyss of careless reporting and self-serving utility. The news report in

Science

magazine by Elizabeth Pennisi (September 5, 1997) told the story well, under an accurate headline (“Haeckel's embryos: fraud rediscovered”) and a textual acknowledgment of “Haeckel's work, first found to be flawed more than a century ago.” But the shorter squib in Britain's

New Scientist

(September 6, 1997) began the downward spiral by implying that Richardson had discovered Haeckel's misdeed for the first time.

As so often happens, this ersatz version, so eminently more newsworthy than the truth, opened the floodgates to the following sensationalist (and nonsensical) account: a primary pillar of Darwinism, and of evolution in general, has been revealed as fraudulent after more than a century of continuous and unchallenged centrality in biological theory. If evolution rests upon such flimsy support, perhaps we should question the entire enterprise and give creationists, who have always flubbed their day in court, their day in the classroom.

Michael Behe, a Lehigh University biologist who has tried to resuscitate the most ancient and tired canard in the creationist arsenal (Paley's “argument from design,” based on the supposed “irreducible complexity” of intricate biological structures, a claim well refuted by Darwin himself in his famous discussion of transitional forms in the evolution of complex eyes), reached the

nadir in an op-ed piece for the

New York Times

(August 13, 1999), commenting on the Kansas School Board's decision to make instruction in evolution optional within the state's science curriculumâan antediluvian move, fortunately reversed in February 2001, following the political successes of scientists, activists, and folks of goodwill (and judgment) in general, in voting fundamentalists off the state school board and replacing them with elected members committed to principles of good education and respect for nature's factuality. (In fairness, I liked Behe's general argument in this piece, for he stayed away from irrelevant religious issues and attacked the Kansas decision by saying that he would never get a chance to present his supposed refutations if students didn't study evolution at all.)