I Have Landed (60 page)

Authors: Stephen Jay Gould

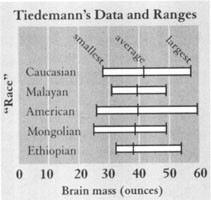

My compilation of average values of brain mass for each race, as calculated from raw data that Tiedemann presented but did not use for such a calculation

.

My appended graph of Tiedemann's uncalculated data does validate his position. The ranges are large and fully overlapping for the crucial comparison of Caucasians and Ethiopians (with the substantially larger Caucasian sample including the smallest and the largest single skull for the entire sample of both groups, as expected). The differences in mean values are tiny compared with the ranges, and, for this reason, probably of no significance in the judgment of intelligence. Moreover, the small variation among means probably reflects differences in body size rather than any stable distinction among racesâand Tiedemann had documented the positive correlation of brain and body size in asserting the equality of brains in men and women (as previously cited). Tiedemann's own data indicate the probable control of mean differences in brain weight by body size. He divides his Caucasian chart into two parts by geographyâfor Europeans and Asians (mostly East Indians). He also notes that Caucasian males from Asia tend to be quite small in body size. Note that his mean brain size for these (presumably smallest-bodied) Caucasians from Asia stands at 36.04 ounces, the minimal value of his entire chart, lying well below the Ethiopian mean of 37.84 ounces.

But data can be “massaged” to advance almost any desired point, even when nothing “technically” inaccurate mars the presentation. For example, the mean differences in Tiedemann's data look trivial when properly scaled against the large ranges of each sample. But if I expand the scale, amalgamate the European and Asian Caucasians into one sample (Tiedemann kept them separate), omit the ranges, and plot only the mean values in conventional order of nineteenth-century racial rankings, the distinctions can be made to seem quite large, and an unsophisticated observer might well conclude that significant differences in intrinsic mental capacity had been documented.

A different presentation of both ranges and average values for the brain mass of each major race, calculated by me from Tiedemann's data. Note that the mean values (the vertical black line in the middle of each horizontal white bar, representing the full ranges for each race) scarcely differ in comparison with the full overlap of ranges, thus validating Tiedemann's general conclusion

.

In conclusion, since Tiedemann clearly approached his study of racial differences with a predisposition toward egalitarian conclusions, and since he differed from nearly all his scientific colleagues in promoting this result, we must seek the source for his defense largely outside the quality and persuasive character of his data. Indeed, and scarcely surprising for an issue so salient in Tiedemann's time and so continually troubling and tragic ever since, he based his judgment on a moral question that, as he well understood, empirical data might illuminate but could never resolve: the social evils of racism, and particularly of slavery.

Tiedemann recognized that scientific data about facts of nature could not validate moral judgments about the evils of slaveryâas conquerors could always invent other justifications for enslaving people judged equal to themselves in mental might, while many abolitionists accepted the inferiority of black Africans, but argued all the more strongly for freedom because decency requires special kindness toward those not so well suited for success. But Tiedemann also appreciated a social reality that blurred the logical separation of facts and morals: in practice, most supporters of slavery promoted inferiority as an argument for tolerating an institution that would otherwise be hard to justify under a rubric of supposedly “Christian” values: if “they” are not like “us,” and if “they” are too benighted to govern themselves in the complexities of modern living, then “we” gain the right to take over. If scientific facts pointed to equality of intellectual capacity, then many conventional arguments for slavery would fall.

Modern scientific journals generally insist upon the exclusion of overt moral

arguments from ostensibly factual accounts of natural phenomena. But the more literary standards and interdisciplinary preferences of Tiedemann's time permitted far more license, even in leading scientific journals like the

Philosophical Transactions

(an appropriate, if now slightly archaic, name used by this great scientific journal since its foundation in the seventeenth century). Tiedemann could therefore state his extrascientific reasons literally “up front”âfor the first paragraph of his article announces

both

his scientific and ethical motives, and also resolves the puzzle of his decision to publish in English:

I take the liberty of presenting to the Royal Society a paper on a subject which appears to me to be of great importance in the natural history, anatomy, and physiology of Man; interesting also in a political and legislative point of view. Celebrated naturalists . . . look upon the Negroes as a race inferior to the European in organization and intellectual powers, having much resemblance with the Monkey. . . . Were it proved to be correct, the Negro would occupy a different situation in society from that which has been so lately given him by the noble British Government.

In short, Tiedemann published his paper in English to honor and commemorate the abolition of the slave trade in Great Britain. The process had been long and tortuous (also torturous). Under the vigorous prodding of such passionate abolitionists as William Wilberforce, Britain had abolished the West Indian slave trade in 1807, but had not freed those already enslaved. (Wilberforce's son, Bishop Samuel, aka “Soapy Sam,” Wilberforce became an equally passionate anti-Darwinianâfor what goes around admirably can come around ridiculously, and history often repeats itself by Marx's motto, “the first time as tragedy, the second as farce.”) Full manumission, with complete abolition, did not occur until 1834âa great event in human history that Tiedemann chose to celebrate in the most useful manner he could devise in his role as a professional scientist: by writing a technical article to promote a true argument that, he hoped, would do some moral good as well.

I cited Tiedemann's opening paragraph to praise his wise mixture of factual information and moral concern, and to resolve the puzzle of his publication in a foreign tongue. I can only end with his closing paragraph, an even more forceful statement of the moral theme, and a testimony to a most admirable man, whom history has forgotten, but who did his portion of good with the tools that his values, his intellectual gifts, and his sense of purpose had provided:

The principal result of my researches on the brain of the Negro is, that neither anatomy nor physiology can justify our placing them beneath the Europeans in a moral or intellectual point of view. How is it possible, then, to deny that the Ethiopian race is capable of civilization? This is just as false as it would have been in the time of Julius Caesar to have considered the Germans, Britons, Helvetians, and Batavians incapable of civilization. The slave trade was the proximate and remote reason of the innumerable evils which retarded the civilization of the African tribes. Great Britain has achieved a noble and splendid act of national justice in abolishing the slave trade. The chain which bound Africa to the dust, and prevented the success of every effort that was made to raise her, is broken.

Triumph and Tragedy on the Exact Centennial of

I Have Landed

, September 11, 2001

Introductory Statement

T

HE

FOUR SHORT PIECES IN THIS FINAL SECTION, ADDED

for obvious and tragic reasons after the completion of this book in its original form, chronicle an odyssey of fact and feeling during the month following an epochal moment that may well be named, in history's archives, simply by its date rather than its cardinal eventânot D-Day, not the day of JFK's assassination, but simply as “September 11th.” I would not have been able to bypass the subject in any case, but I simply couldn't leave this transformation of our lives and sensibilities unaddressed in this book, because my focus and titleâ

I Have Landed

âmemorializes the beginning of my family in America at my grandfather's arrival on September 11, 1901, exactly, in the most eerie coincidence that I have ever viscerally experienced, 100 years to the day before our recent tragedy, centered less than a mile from my New York home. The four pieces in this set consciously treat the same theme, and build upon each other by carrying

the central thought, and some actual phrases as well, from one piece to the next in sequenceâa kind of repetition that I usually shun with rigor in essay collections, but that seems right, even required, in this singular circumstance. For I have felt such a strong need, experienced emotionally almost as a duty, to emphasize a vital but largely invisible theme of true redemption, so readily lost in the surrounding tragedy, but flowing from an evolutionary biologist's professional view of complex systems in general, and human propensities in particular: the overwhelming predominance of simple decency and goodness, a central aspect of our being as a species, yet so easily obscured by the efficacy of rare acts of spectacularly destructive evil. Thus, one might call this section “four changes rung on the same theme of tough hope and steadfast human nature”âas my chronology moves from some first thoughts in “exile” in Halifax, to first impressions upon returning home to Ground Zero, to musings on the stunning coincidence at the centennial of

I Have Landed

, to more general reflections, at a bit more emotional distance, of a lifelong New Yorker upon the significance of his city's great buildings and their symbolic meaning for human hope and transcendence.

The Good People of Halifax

16

I

MAGES

OF DIVISION AND ENMITY MARKED MY FIRST CON

tact, albeit indirect, with Nova Scotiaâthe common experience of so many American schoolchildren grappling with the unpopular assignment of Longfellow's epic poem

Evangeline

, centered upon the expulsion of the Acadians in 1755. My first actual encounter with Maritime Canada, as a teenager on a family motor trip in the mid-1950s, sparked nothing but pleasure and fascination, as I figured out the illusion of Moncton's magnetic hill, marveled at the tidal phenomena of the Bay of Fundy (especially the reversing rapids of Saint John and the tidal bore of Moncton), found peace of spirit at Peggy's Cove, and learned some history in the old streets of Halifax.

I have been back, always with eagerness and fulfillment, a few times since, for reasons both recreational and professionalâa second family trip, one generation later, and now as a father with two sons aged 3 and in utero; a lecture at Dalhousie; or some geological field work in Newfoundland. My latest visit among you, however, was entirely involuntary and maximally stressful. I live in lower Manhattan, just one mile from the burial ground of the Twin Towers. As they fell victim to evil and insanity on Tuesday, September 11, during the morning after my sixtieth birthday, my wife and I, en route from Milan to New York, flew over the

Titanic

's resting place and then followed the route of her recovered dead to Halifax. We sat on the tarmac for eight hours, and eventually proceeded to the cots of Dartmouth's sports complex, then upgraded to the adjacent Holiday Inn. On Friday, at three o'clock in the morning, Alitalia brought us back to the airport, only to inform us that their plane would return to Milan. We rented one of the last two cars available and drove, with an intense mixture of grief and relief, back home.

The general argument of this piece, amidst the most horrific specifics of any event in our lifetime, does not state the views of a naively optimistic Pollyanna, but rather, and precisely to the contrary, attempts to record one of the deepest tragedies of our existence. Intrinsic human goodness and decency prevail effectively all the time, and the moral compass of nearly every person, despite some occasional jiggling prompted by ordinary human foibles, points in the right direction. The oppressive weight of disaster and tragedy in our lives does not arise from a high percentage of evil among the summed total of all acts, but from the extraordinary power of exceedingly rare incidents of depravity to inflict catastrophic damage, especially in our technological age when airplanes can become powerful bombs. (An even more evil man, armed only with a longbow, could not have wreaked such havoc at the Battle of Agincourt in 1415.)

In an important, little appreciated, and utterly tragic principle regulating the structure of nearly all complex systems, building up must be accomplished step by tiny step, whereas destruction need occupy but an instant. In previous essays on the nature of change, I have called this phenomenon the Great Asymmetry (with uppercase letters to emphasize the sad generality). Ten thousand acts of kindness done by thousands of people, and slowly building trust and harmony over many years, can be undone by one destructive act of a skilled and committed psychopath. Thus, even if the

effects

of kindness and evil balance out in the course of history, the Great Asymmetry guarantees that the

numbers

of kind and evil people could hardly differ more, for thousands of good souls overwhelm each perpetrator of darkness.